In the world of concurrent programming and operating systems, synchronization primitives are essential tools that prevent race conditions and ensure thread safety. Among these, Mutex and Semaphore are two fundamental mechanisms that every developer should understand thoroughly.

This comprehensive guide will explore the differences, similarities, use cases, and implementation details of both Mutex and Semaphore, helping you choose the right synchronization primitive for your specific needs.

Understanding Synchronization Primitives

Before diving into the specifics of Mutex and Semaphore, let’s establish what synchronization primitives are and why they’re crucial in concurrent programming.

Synchronization primitives are low-level constructs provided by operating systems to coordinate access to shared resources among multiple threads or processes. They prevent race conditions, ensure data consistency, and maintain program correctness in multi-threaded environments.

What is a Mutex?

A Mutex (Mutual Exclusion) is a synchronization primitive that provides exclusive access to a shared resource. It’s essentially a binary lock that can be in one of two states: locked or unlocked.

Key Characteristics of Mutex

- Binary Nature: Only one thread can acquire a mutex at a time

- Ownership: The thread that locks the mutex must be the one to unlock it

- Blocking: Threads attempting to acquire a locked mutex will block until it’s released

- Priority Inheritance: Often supports priority inheritance to prevent priority inversion

Mutex Implementation Example

Here’s a practical example demonstrating mutex usage in C++:

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <mutex>

#include <vector>

std::mutex mtx;

int shared_counter = 0;

void increment_counter(int thread_id) {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; ++i) {

mtx.lock(); // Acquire mutex

shared_counter++; // Critical section

std::cout << "Thread " << thread_id

<< ": " << shared_counter << std::endl;

mtx.unlock(); // Release mutex

}

}

int main() {

std::vector<std::thread> threads;

// Create 3 threads

for (int i = 0; i < 3; ++i) {

threads.emplace_back(increment_counter, i);

}

// Wait for all threads to complete

for (auto& t : threads) {

t.join();

}

std::cout << "Final counter value: " << shared_counter << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Expected Output:

Thread 0: 1

Thread 1: 2

Thread 2: 3

Thread 0: 4

...

Final counter value: 3000

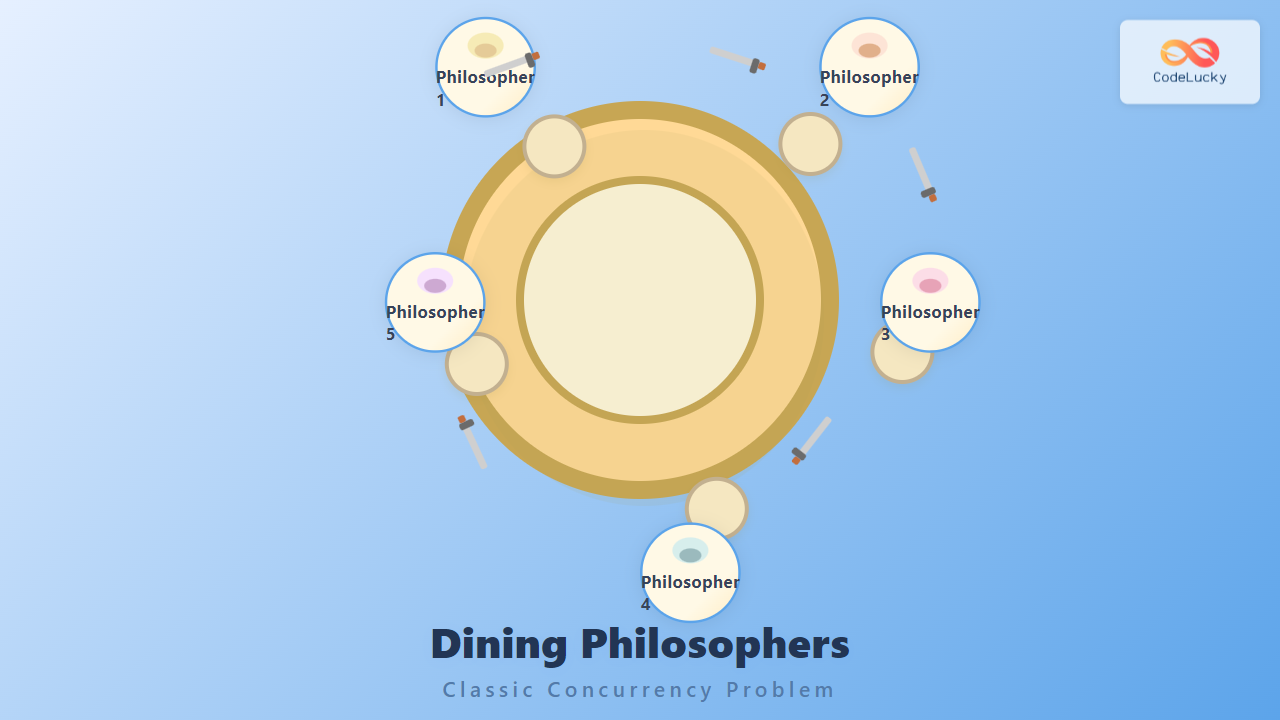

What is a Semaphore?

A Semaphore is a signaling mechanism that controls access to a shared resource by maintaining a counter. Unlike a mutex, a semaphore can allow multiple threads to access a resource simultaneously, up to a specified limit.

Types of Semaphores

1. Binary Semaphore

Similar to a mutex, with values 0 or 1. However, unlike mutex, any thread can signal (increment) the semaphore.

2. Counting Semaphore

Maintains a counter that can have any non-negative integer value, allowing multiple threads to access the resource simultaneously.

Key Characteristics of Semaphore

- Counter-based: Maintains an internal counter

- No ownership: Any thread can signal (increment) the semaphore

- Resource counting: Can control access to multiple instances of a resource

- Signaling mechanism: Used for thread synchronization and communication

Semaphore Implementation Example

Here’s a practical example using semaphores to control access to a limited resource pool:

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <semaphore>

#include <vector>

#include <chrono>

std::counting_semaphore<3> resource_pool(3); // Allow 3 concurrent accesses

void use_resource(int thread_id) {

resource_pool.acquire(); // Wait for available resource

std::cout << "Thread " << thread_id

<< " acquired resource" << std::endl;

// Simulate resource usage

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::seconds(2));

std::cout << "Thread " << thread_id

<< " releasing resource" << std::endl;

resource_pool.release(); // Release resource

}

int main() {

std::vector<std::thread> threads;

// Create 6 threads competing for 3 resources

for (int i = 0; i < 6; ++i) {

threads.emplace_back(use_resource, i);

}

for (auto& t : threads) {

t.join();

}

return 0;

}

Expected Output:

Thread 0 acquired resource

Thread 1 acquired resource

Thread 2 acquired resource

Thread 0 releasing resource

Thread 3 acquired resource

Thread 1 releasing resource

Thread 4 acquired resource

Thread 2 releasing resource

Thread 5 acquired resource

Thread 3 releasing resource

Thread 4 releasing resource

Thread 5 releasing resource

Mutex vs Semaphore: Detailed Comparison

| Aspect | Mutex | Semaphore |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Mutual exclusion | Signaling and resource counting |

| Value Range | Binary (0 or 1) | Non-negative integers |

| Ownership | Thread-specific ownership | No ownership concept |

| Operations | Lock/Unlock by same thread | Wait/Signal by any thread |

| Resource Access | One thread at a time | Multiple threads (up to counter value) |

| Priority Inheritance | Usually supported | Not applicable |

| Deadlock Prevention | Can cause deadlocks | Less prone to deadlocks |

When to Use Mutex

Choose Mutex when you need:

- Protecting Critical Sections: When only one thread should access shared data at a time

- Thread Ownership: When the same thread that locks must unlock

- Simple Mutual Exclusion: Binary access control to resources

- Priority Inheritance: To prevent priority inversion problems

Common Mutex Use Cases

// Example 1: Protecting shared data structure

std::mutex list_mutex;

std::vector<int> shared_list;

void add_item(int item) {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(list_mutex);

shared_list.push_back(item); // Protected critical section

}

// Example 2: Singleton pattern implementation

class Singleton {

private:

static std::mutex instance_mutex;

static Singleton* instance;

public:

static Singleton* getInstance() {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(instance_mutex);

if (instance == nullptr) {

instance = new Singleton();

}

return instance;

}

};

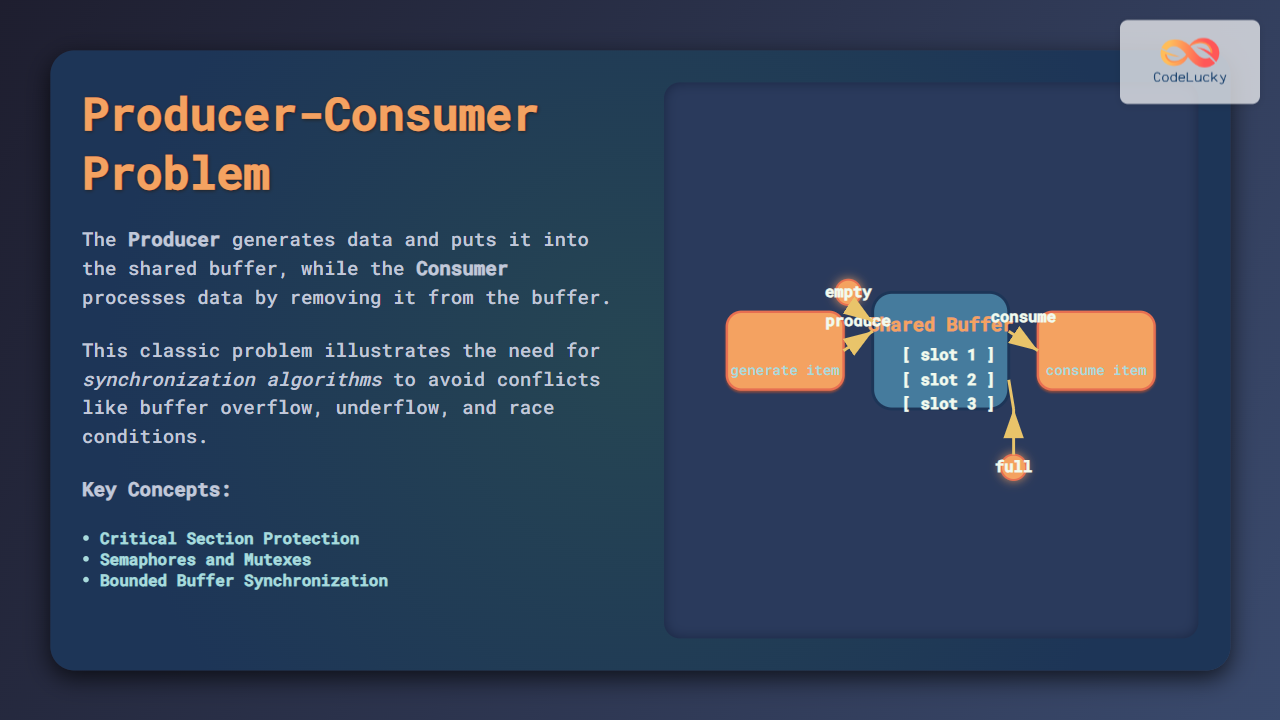

When to Use Semaphore

Choose Semaphore when you need:

- Resource Pool Management: Controlling access to multiple instances of a resource

- Producer-Consumer Scenarios: Coordinating between producer and consumer threads

- Thread Signaling: Communication between threads without data sharing

- Rate Limiting: Controlling the number of concurrent operations

Producer-Consumer Example with Semaphores

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <semaphore>

#include <queue>

#include <mutex>

const int BUFFER_SIZE = 5;

std::queue<int> buffer;

std::mutex buffer_mutex;

std::counting_semaphore<BUFFER_SIZE> empty_slots(BUFFER_SIZE);

std::counting_semaphore<BUFFER_SIZE> filled_slots(0);

void producer(int id) {

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i) {

empty_slots.acquire(); // Wait for empty slot

{

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(buffer_mutex);

buffer.push(i);

std::cout << "Producer " << id << " produced: " << i << std::endl;

}

filled_slots.release(); // Signal filled slot

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(100));

}

}

void consumer(int id) {

for (int i = 0; i < 5; ++i) {

filled_slots.acquire(); // Wait for filled slot

int item;

{

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(buffer_mutex);

item = buffer.front();

buffer.pop();

std::cout << "Consumer " << id << " consumed: " << item << std::endl;

}

empty_slots.release(); // Signal empty slot

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(150));

}

}

Performance Considerations

Performance Comparison

| Metric | Mutex | Semaphore |

|---|---|---|

| Memory Overhead | Lower (simple flag) | Higher (counter + queue) |

| Context Switching | Frequent blocking | Better resource utilization |

| Cache Performance | Better locality | Potential cache misses |

| Scalability | Limited to 1 thread | Scales with counter value |

Common Pitfalls and Best Practices

Mutex Best Practices

- Always Use RAII: Use lock_guard or unique_lock for automatic unlocking

- Minimize Critical Sections: Keep locked regions as small as possible

- Avoid Recursive Locking: Unless using recursive_mutex specifically

- Consistent Lock Ordering: Always acquire locks in the same order to prevent deadlocks

Semaphore Best Practices

- Initialize Correctly: Set the initial counter value appropriately

- Match Acquire/Release: Ensure every acquire has a corresponding release

- Avoid Overflow: Don’t release more than the maximum allowed value

- Consider Timeouts: Use timed operations to avoid indefinite blocking

Common Pitfalls

// ❌ DON'T: Forgetting to unlock mutex

void bad_mutex_usage() {

mtx.lock();

if (some_condition) {

return; // Mutex never unlocked!

}

mtx.unlock();

}

// ✅ DO: Use RAII with lock_guard

void good_mutex_usage() {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(mtx);

if (some_condition) {

return; // Mutex automatically unlocked

}

}

// ❌ DON'T: Mismatched semaphore operations

void bad_semaphore_usage() {

sem.acquire();

// Forgot to call sem.release()

}

// ✅ DO: Always match acquire with release

void good_semaphore_usage() {

sem.acquire();

try {

// Critical work

sem.release();

} catch (...) {

sem.release(); // Release even on exception

throw;

}

}

Advanced Synchronization Patterns

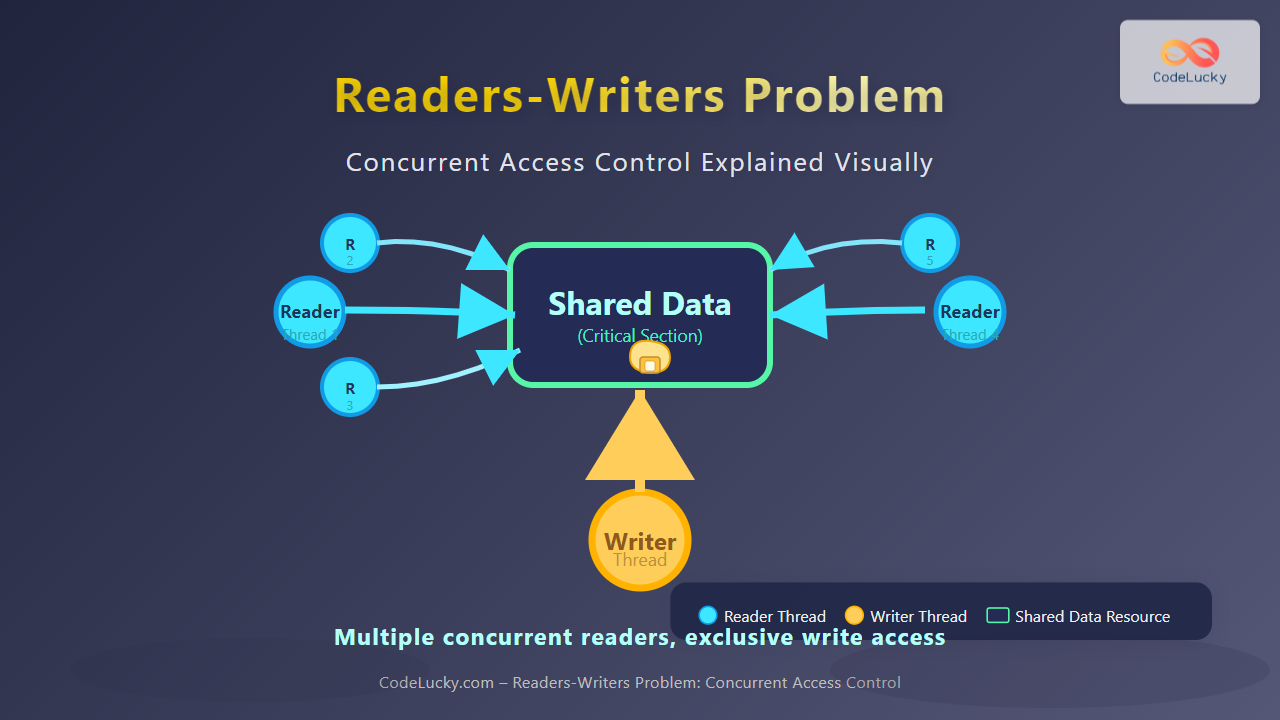

Reader-Writer Lock Pattern

While not a direct comparison between mutex and semaphore, understanding how they can work together is valuable:

class ReadWriteLock {

private:

std::mutex mutex_;

std::condition_variable cv_;

int readers_ = 0;

bool writer_ = false;

public:

void read_lock() {

std::unique_lock<std::mutex> lock(mutex_);

cv_.wait(lock, [this] { return !writer_; });

++readers_;

}

void read_unlock() {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(mutex_);

--readers_;

if (readers_ == 0) {

cv_.notify_all();

}

}

void write_lock() {

std::unique_lock<std::mutex> lock(mutex_);

cv_.wait(lock, [this] { return !writer_ && readers_ == 0; });

writer_ = true;

}

void write_unlock() {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(mutex_);

writer_ = false;

cv_.notify_all();

}

};

Real-World Applications

Database Connection Pooling

Semaphores are perfect for managing database connection pools:

class ConnectionPool {

private:

std::counting_semaphore<10> available_connections{10};

std::queue<Connection*> connections;

std::mutex pool_mutex;

public:

Connection* acquire_connection() {

available_connections.acquire();

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(pool_mutex);

Connection* conn = connections.front();

connections.pop();

return conn;

}

void release_connection(Connection* conn) {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(pool_mutex);

connections.push(conn);

available_connections.release();

}

};

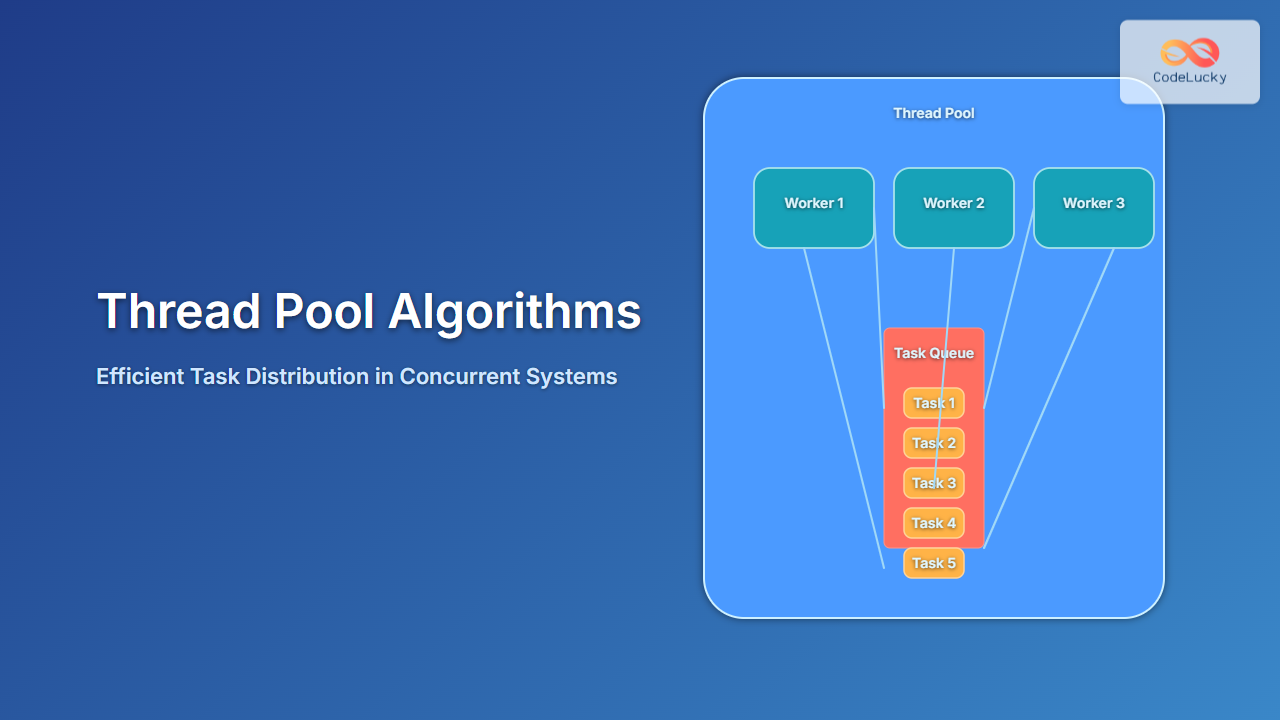

Thread Pool Implementation

Mutexes are essential for protecting shared work queues in thread pools:

class ThreadPool {

private:

std::queue<std::function<void()>> tasks;

std::mutex queue_mutex;

std::condition_variable cv;

bool stop = false;

public:

template<class F>

void enqueue(F&& f) {

{

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(queue_mutex);

tasks.emplace(std::forward<F>(f));

}

cv.notify_one();

}

void worker() {

while (true) {

std::function<void()> task;

{

std::unique_lock<std::mutex> lock(queue_mutex);

cv.wait(lock, [this] { return stop || !tasks.empty(); });

if (stop && tasks.empty()) return;

task = std::move(tasks.front());

tasks.pop();

}

task();

}

}

};

Conclusion

Understanding the differences between Mutex and Semaphore is crucial for effective concurrent programming. Here’s a quick summary to guide your choice:

- Use Mutex when: You need mutual exclusion, thread ownership is important, or you’re protecting simple critical sections

- Use Semaphore when: You need to control access to multiple resources, implement producer-consumer patterns, or coordinate between threads through signaling

Both synchronization primitives serve different purposes and understanding their strengths and limitations will help you build robust, efficient concurrent applications. Remember that the choice between them depends on your specific use case, performance requirements, and the nature of the resources you’re protecting.

The key to mastering concurrent programming lies in understanding not just how these primitives work, but when and why to use each one. With the examples and patterns provided in this guide, you’re well-equipped to make informed decisions about synchronization in your next project.