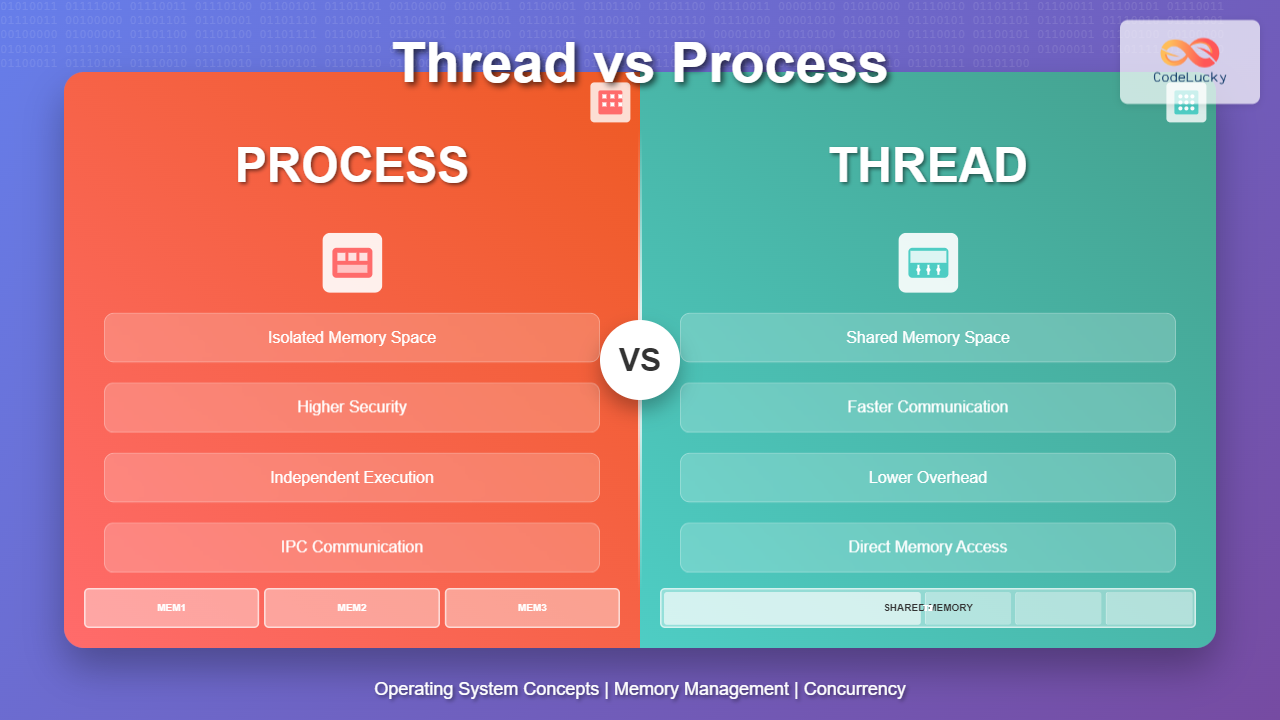

Understanding the fundamental differences between threads and processes is crucial for system programming, application design, and performance optimization. While both enable concurrent execution, they differ significantly in resource usage, communication mechanisms, and implementation complexity.

What is a Process?

A process is an independent execution unit that contains a complete copy of the program code, data, and system resources. Each process runs in its own memory space, completely isolated from other processes.

Key Characteristics of Processes

- Memory Isolation: Each process has its own virtual address space

- Resource Ownership: Processes own file handles, network connections, and system resources

- Independent Execution: Processes can run independently without affecting others

- Security: Strong isolation provides security boundaries

Process Creation Example

Here’s how process creation works in different operating systems:

Linux/Unix – fork() System Call

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

int main() {

pid_t pid;

printf("Before fork(): PID = %d\n", getpid());

pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

// Child process

printf("Child process: PID = %d, Parent PID = %d\n",

getpid(), getppid());

return 0;

} else if (pid > 0) {

// Parent process

printf("Parent process: PID = %d, Child PID = %d\n",

getpid(), pid);

wait(NULL); // Wait for child to complete

return 0;

} else {

// Fork failed

perror("fork failed");

return 1;

}

}

Expected Output:

Before fork(): PID = 1234

Parent process: PID = 1234, Child PID = 1235

Child process: PID = 1235, Parent PID = 1234

Windows – CreateProcess() API

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

STARTUPINFO si;

PROCESS_INFORMATION pi;

ZeroMemory(&si, sizeof(si));

si.cb = sizeof(si);

ZeroMemory(π, sizeof(pi));

// Create child process

if (CreateProcess(

"notepad.exe", // Application name

NULL, // Command line

NULL, // Process security attributes

NULL, // Thread security attributes

FALSE, // Inherit handles

0, // Creation flags

NULL, // Environment

NULL, // Current directory

&si, // Startup info

π)) { // Process info

printf("Process created successfully!\n");

printf("Process ID: %d\n", pi.dwProcessId);

// Wait for process to complete

WaitForSingleObject(pi.hProcess, INFINITE);

// Close handles

CloseHandle(pi.hProcess);

CloseHandle(pi.hThread);

} else {

printf("CreateProcess failed (%d)\n", GetLastError());

}

return 0;

}

What is a Thread?

A thread is a lightweight execution unit within a process that shares the process’s memory space and resources. Multiple threads can exist within a single process, enabling concurrent execution while sharing data efficiently.

Key Characteristics of Threads

- Shared Memory: All threads share the same memory space

- Lightweight: Minimal overhead for creation and context switching

- Fast Communication: Direct memory access for inter-thread communication

- Shared Resources: File handles, network connections shared among threads

Thread Creation Examples

POSIX Threads (pthread)

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <unistd.h>

// Shared global variable

int counter = 0;

void* thread_function(void* arg) {

int thread_id = *(int*)arg;

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

printf("Thread %d: Counter = %d\n", thread_id, ++counter);

sleep(1);

}

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t threads[3];

int thread_ids[3] = {1, 2, 3};

printf("Creating threads...\n");

// Create threads

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

if (pthread_create(&threads[i], NULL, thread_function, &thread_ids[i]) != 0) {

perror("pthread_create failed");

return 1;

}

}

// Wait for all threads to complete

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

pthread_join(threads[i], NULL);

}

printf("All threads completed. Final counter: %d\n", counter);

return 0;

}

Expected Output:

Creating threads...

Thread 1: Counter = 1

Thread 2: Counter = 2

Thread 3: Counter = 3

Thread 1: Counter = 4

Thread 2: Counter = 5

Thread 3: Counter = 6

...

All threads completed. Final counter: 15

Windows Threads

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

DWORD WINAPI ThreadFunction(LPVOID lpParam) {

int thread_id = *(int*)lpParam;

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

printf("Thread %d: Iteration %d\n", thread_id, i + 1);

Sleep(1000); // Sleep for 1 second

}

return 0;

}

int main() {

HANDLE threads[3];

DWORD thread_ids[3];

int ids[3] = {1, 2, 3};

printf("Creating Windows threads...\n");

// Create threads

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

threads[i] = CreateThread(

NULL, // Security attributes

0, // Stack size

ThreadFunction, // Thread function

&ids[i], // Parameter

0, // Creation flags

&thread_ids[i]); // Thread ID

if (threads[i] == NULL) {

printf("CreateThread failed (%d)\n", GetLastError());

return 1;

}

}

// Wait for all threads

WaitForMultipleObjects(3, threads, TRUE, INFINITE);

// Close thread handles

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

CloseHandle(threads[i]);

}

printf("All threads completed!\n");

return 0;

}

Key Differences Between Threads and Processes

| Aspect | Process | Thread |

|---|---|---|

| Memory Space | Separate address space for each process | Shared address space within process |

| Creation Cost | High (complete memory copy) | Low (minimal overhead) |

| Context Switching | Expensive (full context save/restore) | Fast (minimal context switching) |

| Communication | IPC mechanisms (pipes, sockets, shared memory) | Direct memory access |

| Isolation | Complete isolation | No isolation (shared memory) |

| Failure Impact | Isolated (one process crash doesn’t affect others) | Shared (one thread crash can affect entire process) |

| Security | High (separate address spaces) | Lower (shared memory vulnerabilities) |

| Scalability | Limited by system resources | Better scalability within process limits |

Performance Comparison

Benchmark Example

#include <stdio.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#define NUM_OPERATIONS 1000000

void* thread_work(void* arg) {

int sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_OPERATIONS; i++) {

sum += i;

}

return NULL;

}

void process_work() {

int sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_OPERATIONS; i++) {

sum += i;

}

}

int main() {

clock_t start, end;

// Benchmark thread creation

printf("Benchmarking thread creation...\n");

start = clock();

pthread_t threads[4];

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

pthread_create(&threads[i], NULL, thread_work, NULL);

}

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

pthread_join(threads[i], NULL);

}

end = clock();

double thread_time = ((double)(end - start)) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC;

printf("Thread execution time: %.4f seconds\n", thread_time);

// Benchmark process creation

printf("\nBenchmarking process creation...\n");

start = clock();

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

pid_t pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

process_work();

exit(0);

}

}

// Wait for all child processes

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

wait(NULL);

}

end = clock();

double process_time = ((double)(end - start)) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC;

printf("Process execution time: %.4f seconds\n", process_time);

printf("\nPerformance ratio (Process/Thread): %.2fx\n",

process_time / thread_time);

return 0;

}

Communication Mechanisms

Inter-Process Communication (IPC)

Processes require special mechanisms for communication:

1. Pipes

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main() {

int pipefd[2];

pid_t pid;

char buffer[100];

char message[] = "Hello from parent process!";

// Create pipe

if (pipe(pipefd) == -1) {

perror("pipe failed");

return 1;

}

pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

// Child process - reader

close(pipefd[1]); // Close write end

read(pipefd[0], buffer, sizeof(buffer));

printf("Child received: %s\n", buffer);

close(pipefd[0]);

} else {

// Parent process - writer

close(pipefd[0]); // Close read end

write(pipefd[1], message, strlen(message) + 1);

printf("Parent sent: %s\n", message);

close(pipefd[1]);

}

return 0;

}

2. Shared Memory

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/shm.h>

#include <sys/ipc.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main() {

key_t key = ftok(".", 1);

int shmid = shmget(key, 1024, IPC_CREAT | 0666);

if (fork() == 0) {

// Child process

char* shared_mem = (char*)shmat(shmid, NULL, 0);

strcpy(shared_mem, "Hello from child!");

printf("Child wrote: %s\n", shared_mem);

shmdt(shared_mem);

} else {

// Parent process

sleep(1); // Wait for child

char* shared_mem = (char*)shmat(shmid, NULL, 0);

printf("Parent read: %s\n", shared_mem);

shmdt(shared_mem);

shmctl(shmid, IPC_RMID, NULL); // Remove shared memory

}

return 0;

}

Inter-Thread Communication

Threads communicate directly through shared memory:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <unistd.h>

// Shared data structure

struct shared_data {

int counter;

char message[100];

pthread_mutex_t mutex;

};

struct shared_data shared = {0, "", PTHREAD_MUTEX_INITIALIZER};

void* producer(void* arg) {

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&shared.mutex);

shared.counter++;

sprintf(shared.message, "Message %d from producer", shared.counter);

printf("Producer: %s\n", shared.message);

pthread_mutex_unlock(&shared.mutex);

sleep(1);

}

return NULL;

}

void* consumer(void* arg) {

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

sleep(1);

pthread_mutex_lock(&shared.mutex);

printf("Consumer read: %s (Counter: %d)\n", shared.message, shared.counter);

pthread_mutex_unlock(&shared.mutex);

}

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t prod_thread, cons_thread;

pthread_create(∏_thread, NULL, producer, NULL);

pthread_create(&cons_thread, NULL, consumer, NULL);

pthread_join(prod_thread, NULL);

pthread_join(cons_thread, NULL);

pthread_mutex_destroy(&shared.mutex);

return 0;

}

When to Use Processes

Use processes when:

- Fault Isolation: Critical applications where one component’s failure shouldn’t affect others

- Security Requirements: Different privilege levels or security domains needed

- Independent Services: Microservices architecture or separate application components

- Different Programming Languages: Components written in different languages

- Legacy System Integration: Integrating with existing standalone applications

Real-World Process Examples

# Example: Web server with multiple worker processes

# nginx configuration

worker_processes auto; # One process per CPU core

events {

worker_connections 1024;

use epoll;

}

http {

upstream backend {

server 127.0.0.1:3001; # Process 1

server 127.0.0.1:3002; # Process 2

server 127.0.0.1:3003; # Process 3

}

server {

listen 80;

location / {

proxy_pass http://backend;

}

}

}

When to Use Threads

Use threads when:

- Shared State: Multiple execution units need to access the same data frequently

- Performance Critical: Low latency and high throughput requirements

- Resource Efficiency: Limited memory or need to minimize resource usage

- Fine-grained Parallelism: Breaking down tasks into small, parallel operations

- I/O Bound Operations: Handling multiple I/O operations concurrently

Thread Pool Example

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define THREAD_POOL_SIZE 4

#define TASK_QUEUE_SIZE 20

typedef struct {

void (*function)(void*);

void* argument;

} task_t;

typedef struct {

task_t task_queue[TASK_QUEUE_SIZE];

int queue_front;

int queue_rear;

int queue_count;

pthread_mutex_t queue_mutex;

pthread_cond_t queue_cond;

pthread_t threads[THREAD_POOL_SIZE];

int shutdown;

} thread_pool_t;

thread_pool_t pool;

void* worker_thread(void* arg) {

while (1) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&pool.queue_mutex);

while (pool.queue_count == 0 && !pool.shutdown) {

pthread_cond_wait(&pool.queue_cond, &pool.queue_mutex);

}

if (pool.shutdown) {

pthread_mutex_unlock(&pool.queue_mutex);

break;

}

// Get task from queue

task_t task = pool.task_queue[pool.queue_front];

pool.queue_front = (pool.queue_front + 1) % TASK_QUEUE_SIZE;

pool.queue_count--;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&pool.queue_mutex);

// Execute task

task.function(task.argument);

}

return NULL;

}

void add_task(void (*function)(void*), void* argument) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&pool.queue_mutex);

if (pool.queue_count < TASK_QUEUE_SIZE) {

pool.task_queue[pool.queue_rear].function = function;

pool.task_queue[pool.queue_rear].argument = argument;

pool.queue_rear = (pool.queue_rear + 1) % TASK_QUEUE_SIZE;

pool.queue_count++;

pthread_cond_signal(&pool.queue_cond);

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&pool.queue_mutex);

}

void process_request(void* arg) {

int request_id = *(int*)arg;

printf("Processing request %d by thread %lu\n",

request_id, pthread_self());

sleep(2); // Simulate work

printf("Completed request %d\n", request_id);

free(arg);

}

int main() {

// Initialize thread pool

pool.queue_front = 0;

pool.queue_rear = 0;

pool.queue_count = 0;

pool.shutdown = 0;

pthread_mutex_init(&pool.queue_mutex, NULL);

pthread_cond_init(&pool.queue_cond, NULL);

// Create worker threads

for (int i = 0; i < THREAD_POOL_SIZE; i++) {

pthread_create(&pool.threads[i], NULL, worker_thread, NULL);

}

// Add tasks

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) {

int* request_id = malloc(sizeof(int));

*request_id = i;

add_task(process_request, request_id);

printf("Added request %d to queue\n", i);

}

sleep(15); // Wait for tasks to complete

// Shutdown thread pool

pthread_mutex_lock(&pool.queue_mutex);

pool.shutdown = 1;

pthread_cond_broadcast(&pool.queue_cond);

pthread_mutex_unlock(&pool.queue_mutex);

// Wait for threads to finish

for (int i = 0; i < THREAD_POOL_SIZE; i++) {

pthread_join(pool.threads[i], NULL);

}

pthread_mutex_destroy(&pool.queue_mutex);

pthread_cond_destroy(&pool.queue_cond);

return 0;

}

Best Practices and Common Pitfalls

Process Best Practices

- Resource Management: Always clean up child processes to avoid zombies

- Error Handling: Implement proper error handling for process creation

- Communication Design: Choose appropriate IPC mechanisms based on data volume and frequency

- Security: Use least privilege principle for process permissions

Thread Best Practices

- Synchronization: Always protect shared data with mutexes or other synchronization primitives

- Deadlock Prevention: Establish lock ordering to prevent deadlocks

- Thread Safety: Use thread-safe functions and libraries

- Resource Cleanup: Properly join or detach threads

Common Pitfalls

// WRONG: Race condition in threads

int global_counter = 0;

void* unsafe_increment(void* arg) {

for (int i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

global_counter++; // Race condition!

}

return NULL;

}

// CORRECT: Protected with mutex

pthread_mutex_t counter_mutex = PTHREAD_MUTEX_INITIALIZER;

void* safe_increment(void* arg) {

for (int i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&counter_mutex);

global_counter++;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&counter_mutex);

}

return NULL;

}

Modern Alternatives and Hybrid Approaches

Event-Driven Programming

Modern applications often use event loops and asynchronous I/O to handle concurrency without the overhead of multiple threads or processes:

// Node.js event-driven example

const http = require('http');

const fs = require('fs').promises;

const server = http.createServer(async (req, res) => {

try {

// Non-blocking file read

const data = await fs.readFile('large-file.txt');

res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/plain'});

res.end(data);

} catch (error) {

res.writeHead(500);

res.end('Error reading file');

}

});

server.listen(3000, () => {

console.log('Server running on port 3000');

});

Container and Microservices Architecture

Modern distributed systems often combine both approaches:

- Processes: For service isolation and fault tolerance

- Threads: Within each service for handling concurrent requests

- Event-driven: For I/O-intensive operations

Conclusion

The choice between threads and processes depends on your specific requirements:

Choose processes for: Security, fault isolation, independent services, and different privilege levels.

Choose threads for: Performance-critical applications, shared state, resource efficiency, and fine-grained parallelism.

Modern applications often use hybrid approaches, combining processes for service boundaries with threads for internal concurrency, and event-driven programming for I/O operations. Understanding these fundamental concepts enables you to make informed architectural decisions and write efficient concurrent applications.

Remember that concurrency introduces complexity, so always consider whether the benefits outweigh the added complexity for your specific use case. Start simple and add concurrency only when needed for performance or functionality requirements.