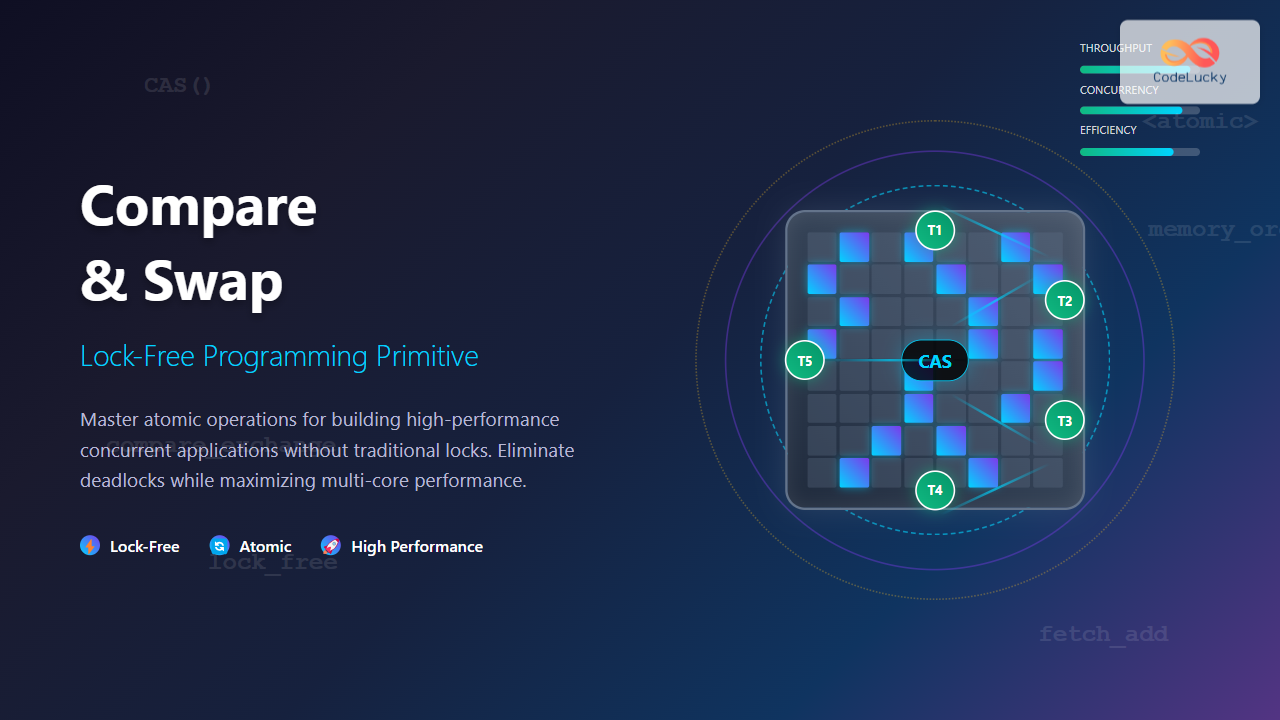

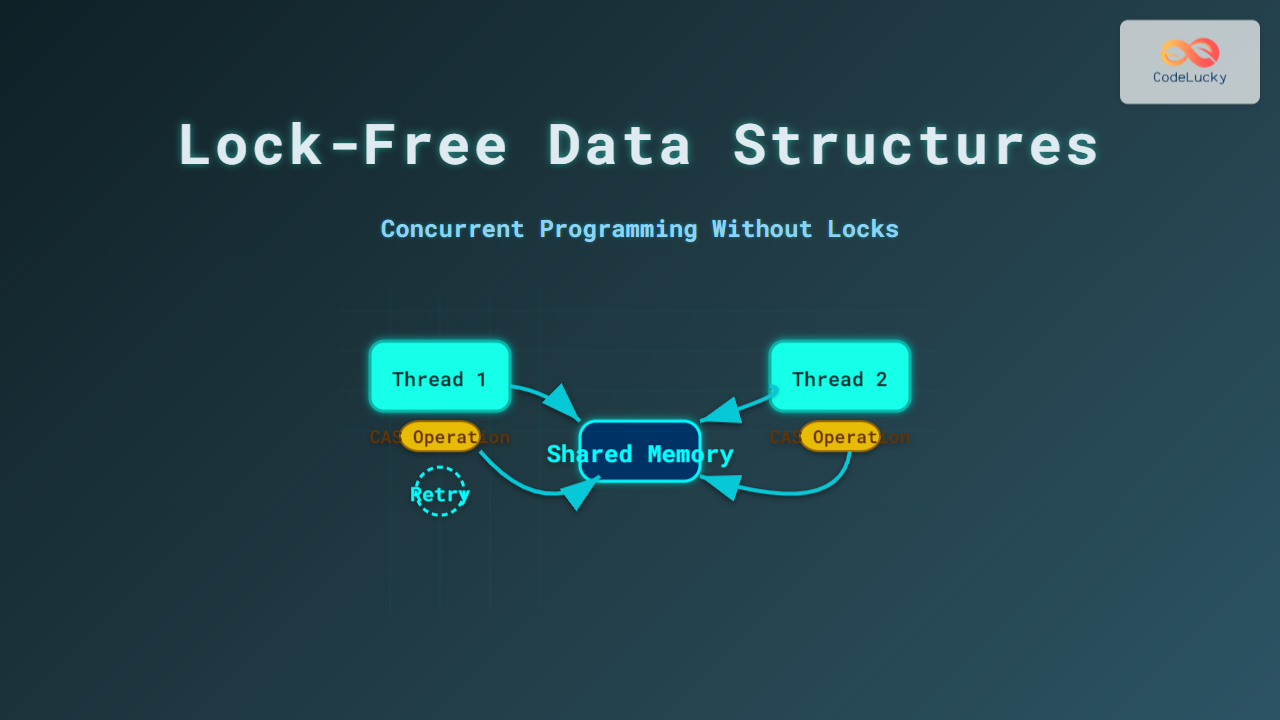

Compare and Swap (CAS) is a fundamental atomic operation that forms the backbone of lock-free programming and high-performance concurrent systems. This powerful primitive allows multiple threads to safely modify shared data without traditional locking mechanisms, resulting in better performance and avoiding common concurrency pitfalls like deadlocks.

What is Compare and Swap (CAS)?

Compare and Swap is an atomic instruction that compares the contents of a memory location with a given value and, only if they match, modifies the contents to a new value. This entire operation happens atomically, meaning it cannot be interrupted by other threads.

The basic CAS operation can be described as:

boolean CAS(memory_location, expected_value, new_value) {

if (*memory_location == expected_value) {

*memory_location = new_value;

return true;

}

return false;

}

How CAS Works Under the Hood

At the hardware level, CAS is implemented as a single atomic instruction supported by modern processors. Different architectures provide different implementations:

- x86/x64: CMPXCHG instruction

- ARM: LDREX/STREX instruction pair

- RISC-V: LR/SC (Load-Reserved/Store-Conditional)

- SPARC: CAS instruction

Memory Ordering and CAS

CAS operations typically provide sequential consistency, ensuring that all threads observe the same order of operations. However, modern implementations often allow specifying memory ordering constraints for better performance:

// C++ example with memory ordering

std::atomic<int> counter{0};

// Sequential consistency (default)

bool success = counter.compare_exchange_weak(expected, desired);

// Relaxed ordering for better performance

bool success = counter.compare_exchange_weak(expected, desired,

std::memory_order_relaxed);

Advantages of Compare and Swap

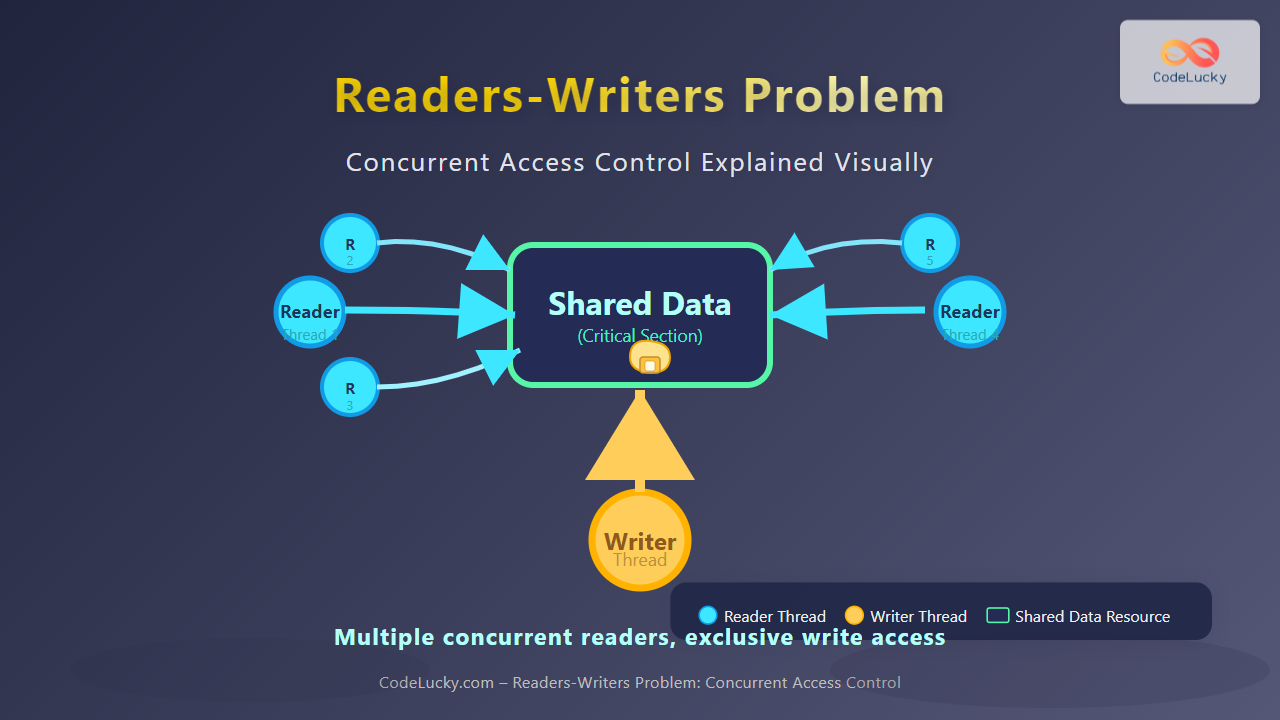

1. Lock-Free Programming

CAS enables lock-free data structures that don’t suffer from the overhead and potential issues of traditional locks:

- No deadlock possibility

- No priority inversion

- Better scalability on multi-core systems

- Reduced context switching overhead

2. Performance Benefits

Lock-free algorithms using CAS often provide superior performance characteristics:

// Performance comparison example (conceptual)

// Traditional lock-based counter

class LockedCounter {

private:

int value = 0;

mutex mtx;

public:

void increment() {

lock_guard<mutex> lock(mtx);

value++;

}

int get() {

lock_guard<mutex> lock(mtx);

return value;

}

};

// Lock-free CAS-based counter

class LockFreeCounter {

private:

atomic<int> value{0};

public:

void increment() {

int current = value.load();

while (!value.compare_exchange_weak(current, current + 1)) {

// Retry until successful

}

}

int get() {

return value.load();

}

};

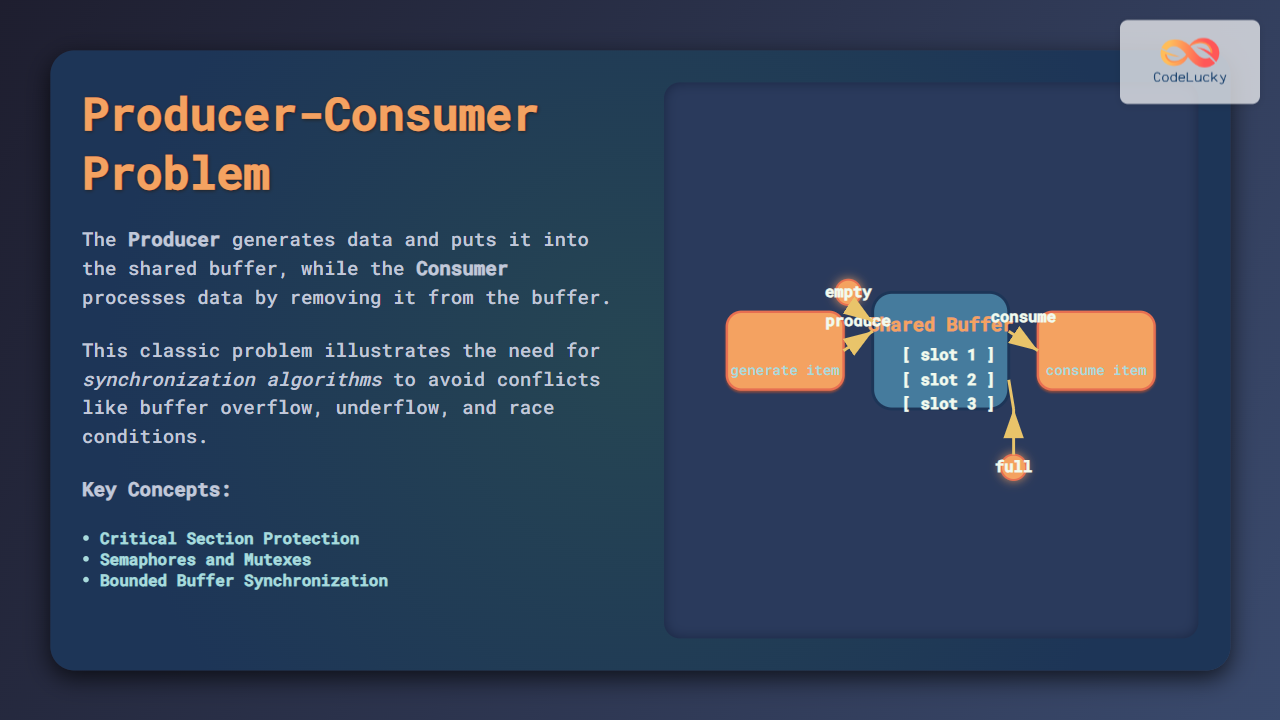

Common Use Cases and Applications

1. Atomic Counters

One of the simplest applications of CAS is implementing atomic counters without locks:

#include <atomic>

#include <thread>

#include <vector>

#include <iostream>

class AtomicCounter {

private:

std::atomic<int> count{0};

public:

void increment() {

int expected = count.load();

while (!count.compare_exchange_weak(expected, expected + 1)) {

// CAS failed, expected was updated with current value

// Loop will retry with the new expected value

}

}

int getValue() const {

return count.load();

}

};

int main() {

AtomicCounter counter;

std::vector<std::thread> threads;

// Launch 10 threads, each incrementing 1000 times

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i) {

threads.emplace_back([&counter]() {

for (int j = 0; j < 1000; ++j) {

counter.increment();

}

});

}

// Wait for all threads to complete

for (auto& t : threads) {

t.join();

}

std::cout << "Final counter value: " << counter.getValue() << std::endl;

// Output: Final counter value: 10000

return 0;

}

2. Lock-Free Stack Implementation

CAS is essential for implementing lock-free data structures like stacks:

template<typename T>

class LockFreeStack {

private:

struct Node {

T data;

Node* next;

Node(T item) : data(std::move(item)), next(nullptr) {}

};

std::atomic<Node*> head{nullptr};

public:

void push(T item) {

Node* new_node = new Node(std::move(item));

new_node->next = head.load();

while (!head.compare_exchange_weak(new_node->next, new_node)) {

// CAS failed, new_node->next was updated with current head

// Retry the operation

}

}

bool pop(T& result) {

Node* old_head = head.load();

while (old_head &&

!head.compare_exchange_weak(old_head, old_head->next)) {

// CAS failed, old_head was updated with current head

// Retry if head is not null

}

if (old_head) {

result = std::move(old_head->data);

delete old_head;

return true;

}

return false; // Stack was empty

}

};

3. Memory Management with CAS

CAS is crucial in memory management systems, particularly for reference counting:

class RefCountedObject {

private:

mutable std::atomic<int> ref_count{0};

public:

void addRef() const {

int current = ref_count.load();

while (!ref_count.compare_exchange_weak(current, current + 1)) {

// Retry until successful

}

}

bool releaseRef() const {

int current = ref_count.load();

while (true) {

if (current == 0) {

return false; // Object already destroyed

}

if (ref_count.compare_exchange_weak(current, current - 1)) {

return current == 1; // Return true if this was the last reference

}

// current was updated by CAS failure, retry

}

}

int getRefCount() const {

return ref_count.load();

}

};

CAS in Different Programming Languages

C++ std::atomic

#include <atomic>

std::atomic<int> value{10};

int expected = 10;

int desired = 20;

// Weak CAS - may fail spuriously on some architectures

if (value.compare_exchange_weak(expected, desired)) {

std::cout << "CAS succeeded" << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "CAS failed, current value: " << expected << std::endl;

}

// Strong CAS - will not fail spuriously

expected = 20;

desired = 30;

if (value.compare_exchange_strong(expected, desired)) {

std::cout << "Strong CAS succeeded" << std::endl;

}

Java AtomicReference

import java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicReference;

public class CASExample {

private AtomicReference<String> atomicString =

new AtomicReference<>("initial");

public boolean updateValue(String expectedValue, String newValue) {

return atomicString.compareAndSet(expectedValue, newValue);

}

public String getValue() {

return atomicString.get();

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

CASExample example = new CASExample();

// This will succeed

boolean success1 = example.updateValue("initial", "updated");

System.out.println("First update: " + success1); // true

// This will fail because expected value doesn't match

boolean success2 = example.updateValue("initial", "failed");

System.out.println("Second update: " + success2); // false

System.out.println("Current value: " + example.getValue()); // "updated"

}

}

Go sync/atomic

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync/atomic"

)

func main() {

var value int64 = 10

// Atomic compare and swap

swapped := atomic.CompareAndSwapInt64(&value, 10, 20)

fmt.Printf("CAS result: %v, new value: %d\n", swapped, value)

// Output: CAS result: true, new value: 20

// This will fail because current value is 20, not 10

swapped = atomic.CompareAndSwapInt64(&value, 10, 30)

fmt.Printf("CAS result: %v, current value: %d\n", swapped, value)

// Output: CAS result: false, current value: 20

}

ABA Problem and Solutions

One of the most significant challenges with CAS operations is the ABA problem, where a value changes from A to B and back to A between CAS operations, potentially causing logical errors.

Example of ABA Problem

// Problematic scenario in a lock-free stack

class ProblematicStack {

struct Node {

int data;

Node* next;

};

std::atomic<Node*> head;

public:

bool pop(int& result) {

Node* old_head = head.load();

if (!old_head) return false;

// DANGER: Between these two operations, another thread might:

// 1. Pop this node (freeing it)

// 2. Push it back (reusing the same memory address)

// 3. The CAS below will succeed even though the stack changed!

Node* new_head = old_head->next;

if (head.compare_exchange_weak(old_head, new_head)) {

result = old_head->data; // Potential use-after-free!

delete old_head;

return true;

}

return false;

}

};

Solutions to ABA Problem

1. Version Numbers/Tags

template<typename T>

class TaggedPointer {

private:

struct TaggedPtr {

T* ptr;

uint64_t tag;

};

std::atomic<TaggedPtr> tagged_ptr;

public:

bool compare_exchange_weak(T* expected_ptr, T* desired_ptr) {

TaggedPtr expected = tagged_ptr.load();

if (expected.ptr != expected_ptr) return false;

TaggedPtr desired = {desired_ptr, expected.tag + 1};

TaggedPtr expected_tagged = {expected_ptr, expected.tag};

return tagged_ptr.compare_exchange_weak(expected_tagged, desired);

}

};

2. Hazard Pointers

class HazardPointer {

static thread_local std::vector<void*> hazard_ptrs;

public:

static void protect(void* ptr) {

hazard_ptrs.push_back(ptr);

}

static void unprotect(void* ptr) {

auto it = std::find(hazard_ptrs.begin(), hazard_ptrs.end(), ptr);

if (it != hazard_ptrs.end()) {

hazard_ptrs.erase(it);

}

}

static bool is_protected(void* ptr) {

return std::find(hazard_ptrs.begin(), hazard_ptrs.end(), ptr) != hazard_ptrs.end();

}

};

Performance Considerations

CAS Performance Characteristics

- Contention Impact: High contention can lead to many CAS failures and retries

- Cache Line Bouncing: Multiple cores competing for the same cache line

- Memory Ordering Overhead: Stronger memory ordering guarantees cost performance

Optimization Techniques

// Exponential backoff to reduce contention

class OptimizedCounter {

private:

std::atomic<int> count{0};

public:

void increment() {

int expected = count.load(std::memory_order_relaxed);

int backoff = 1;

while (!count.compare_exchange_weak(expected, expected + 1,

std::memory_order_relaxed)) {

// Exponential backoff

for (int i = 0; i < backoff; ++i) {

std::this_thread::yield();

}

backoff = std::min(backoff * 2, 1024);

}

}

};

// Batching operations to reduce CAS frequency

class BatchedCounter {

private:

std::atomic<int> global_count{0};

thread_local int local_count = 0;

static const int BATCH_SIZE = 100;

public:

void increment() {

++local_count;

if (local_count >= BATCH_SIZE) {

flush();

}

}

void flush() {

if (local_count > 0) {

int expected = global_count.load();

while (!global_count.compare_exchange_weak(expected,

expected + local_count)) {

// Retry

}

local_count = 0;

}

}

};

When to Use CAS vs Traditional Locks

Use CAS When:

- Operations are simple (increment, swap, etc.)

- Low to moderate contention expected

- Maximum performance is critical

- Avoiding deadlocks is important

- Building foundational concurrent primitives

Use Traditional Locks When:

- Complex multi-step operations need atomicity

- Very high contention scenarios

- Code simplicity is more important than maximum performance

- Working with legacy systems or APIs

Real-World Examples and Benchmarks

Here’s a practical benchmark comparing different synchronization approaches:

#include <chrono>

#include <thread>

#include <vector>

#include <mutex>

#include <atomic>

#include <iostream>

class PerformanceTest {

public:

// Test different counter implementations

static void benchmarkCounters() {

const int NUM_THREADS = 8;

const int INCREMENTS_PER_THREAD = 1000000;

std::cout << "Benchmarking different counter implementations:\n";

std::cout << "Threads: " << NUM_THREADS << ", Increments per thread: "

<< INCREMENTS_PER_THREAD << "\n\n";

// Mutex-based counter

auto mutex_time = benchmarkMutexCounter(NUM_THREADS, INCREMENTS_PER_THREAD);

std::cout << "Mutex counter: " << mutex_time << "ms\n";

// CAS-based counter

auto cas_time = benchmarkCASCounter(NUM_THREADS, INCREMENTS_PER_THREAD);

std::cout << "CAS counter: " << cas_time << "ms\n";

// Relaxed atomic counter

auto relaxed_time = benchmarkRelaxedCounter(NUM_THREADS, INCREMENTS_PER_THREAD);

std::cout << "Relaxed atomic: " << relaxed_time << "ms\n";

std::cout << "\nPerformance improvement:\n";

std::cout << "CAS vs Mutex: " << (double(mutex_time) / cas_time) << "x faster\n";

std::cout << "Relaxed vs CAS: " << (double(cas_time) / relaxed_time) << "x faster\n";

}

private:

static long benchmarkMutexCounter(int threads, int increments) {

int counter = 0;

std::mutex mtx;

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::vector<std::thread> workers;

for (int i = 0; i < threads; ++i) {

workers.emplace_back([&counter, &mtx, increments]() {

for (int j = 0; j < increments; ++j) {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(mtx);

++counter;

}

});

}

for (auto& t : workers) {

t.join();

}

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

return std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::milliseconds>(end - start).count();

}

static long benchmarkCASCounter(int threads, int increments) {

std::atomic<int> counter{0};

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::vector<std::thread> workers;

for (int i = 0; i < threads; ++i) {

workers.emplace_back([&counter, increments]() {

for (int j = 0; j < increments; ++j) {

int expected = counter.load();

while (!counter.compare_exchange_weak(expected, expected + 1)) {

// Retry

}

}

});

}

for (auto& t : workers) {

t.join();

}

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

return std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::milliseconds>(end - start).count();

}

static long benchmarkRelaxedCounter(int threads, int increments) {

std::atomic<int> counter{0};

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::vector<std::thread> workers;

for (int i = 0; i < threads; ++i) {

workers.emplace_back([&counter, increments]() {

for (int j = 0; j < increments; ++j) {

counter.fetch_add(1, std::memory_order_relaxed);

}

});

}

for (auto& t : workers) {

t.join();

}

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

return std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::milliseconds>(end - start).count();

}

};

Advanced CAS Patterns

Double-Width CAS (DCAS)

Some architectures support double-width CAS operations that can atomically update two adjacent memory locations:

// x86-64 CMPXCHG16B example (128-bit CAS)

struct alignas(16) DoubleWord {

uint64_t low;

uint64_t high;

};

bool double_cas(volatile DoubleWord* location,

DoubleWord expected,

DoubleWord desired) {

return __sync_bool_compare_and_swap_16(

reinterpret_cast<volatile __int128*>(location),

*reinterpret_cast<__int128*>(&expected),

*reinterpret_cast<__int128*>(&desired)

);

}

Load-Link/Store-Conditional (LL/SC)

Some architectures provide LL/SC as an alternative to CAS, offering more flexibility:

// Conceptual LL/SC implementation

template<typename T>

class LLSCVariable {

private:

std::atomic<T> value;

thread_local bool reservation_valid = false;

thread_local T reserved_value;

public:

T load_linked() {

reserved_value = value.load();

reservation_valid = true;

return reserved_value;

}

bool store_conditional(T new_value) {

if (!reservation_valid) return false;

T expected = reserved_value;

bool success = value.compare_exchange_strong(expected, new_value);

reservation_valid = false;

return success && (expected == reserved_value);

}

};

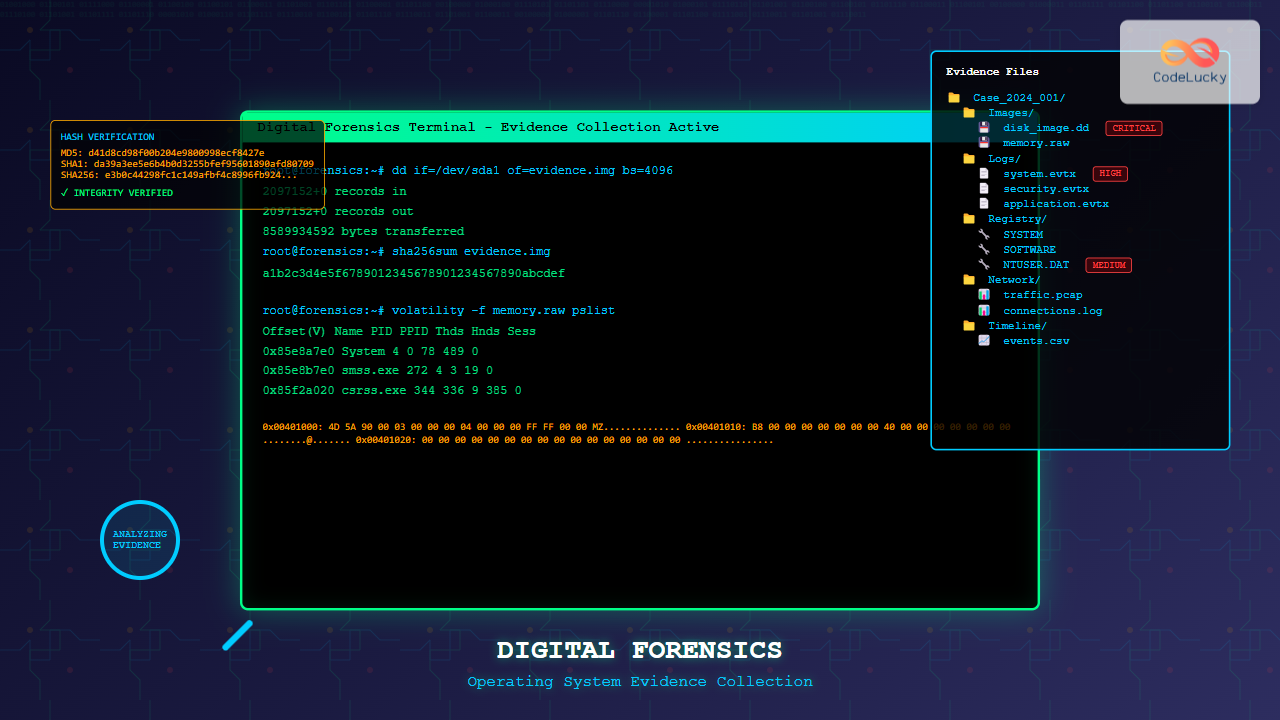

Debugging CAS-Based Code

Debugging lock-free code can be challenging. Here are some strategies:

class DebuggableAtomicCounter {

private:

std::atomic<int> count{0};

std::atomic<uint64_t> cas_attempts{0};

std::atomic<uint64_t> cas_failures{0};

public:

void increment() {

int expected = count.load();

cas_attempts.fetch_add(1, std::memory_order_relaxed);

while (!count.compare_exchange_weak(expected, expected + 1)) {

cas_failures.fetch_add(1, std::memory_order_relaxed);

}

}

void printStats() {

uint64_t attempts = cas_attempts.load();

uint64_t failures = cas_failures.load();

std::cout << "CAS Statistics:\n";

std::cout << " Total attempts: " << attempts << "\n";

std::cout << " Failures: " << failures << "\n";

std::cout << " Success rate: " << (100.0 * (attempts - failures) / attempts) << "%\n";

std::cout << " Current value: " << count.load() << "\n";

}

};

Future of CAS and Lock-Free Programming

The future of CAS and lock-free programming looks promising with several emerging trends:

- Hardware Transactional Memory (HTM): Intel TSX and similar technologies

- Persistent Memory Support: CAS operations for non-volatile memory

- GPU Computing: Atomic operations in CUDA and OpenCL

- Formal Verification: Tools to verify correctness of lock-free algorithms

Conclusion

Compare and Swap is a powerful primitive that enables high-performance lock-free programming. While it comes with challenges like the ABA problem and complexity in debugging, the performance benefits and elimination of traditional locking issues make it an essential tool for system programmers and performance-critical applications.

Key takeaways for using CAS effectively:

- Start simple with atomic counters and basic data structures

- Be aware of the ABA problem and use appropriate mitigation strategies

- Profile your code to ensure CAS provides actual performance benefits

- Consider memory ordering requirements for your specific use case

- Use established libraries and patterns when possible rather than rolling your own

As multi-core systems become increasingly prevalent and performance demands continue to grow, mastering CAS and lock-free programming techniques becomes increasingly valuable for developing efficient concurrent applications.