Spin locks are fundamental synchronization primitives in operating systems that implement busy waiting mechanisms to protect critical sections from concurrent access. Unlike traditional blocking locks, spin locks keep threads actively polling until the lock becomes available, making them essential for low-latency scenarios and kernel-level programming.

What are Spin Locks?

A spin lock is a synchronization mechanism where threads continuously check (spin) for lock availability rather than being put to sleep. When a thread attempts to acquire a busy spin lock, it enters a tight loop, repeatedly testing the lock’s state until it becomes free.

The key characteristic of spin locks is that waiting threads remain active, consuming CPU cycles while polling the lock status. This approach contrasts with blocking locks where threads are suspended and scheduled later.

How Spin Locks Work

Spin locks operate using atomic operations to ensure thread safety. The basic mechanism involves:

- Acquisition Phase: Thread attempts to atomically change lock state from 0 (free) to 1 (locked)

- Spinning Phase: If unsuccessful, thread continuously polls the lock variable

- Critical Section: Once acquired, thread executes protected code

- Release Phase: Thread atomically resets lock state to 0

Basic Spin Lock Implementation

typedef struct {

volatile int locked;

} spinlock_t;

void spinlock_init(spinlock_t *lock) {

lock->locked = 0;

}

void spinlock_acquire(spinlock_t *lock) {

while (__sync_lock_test_and_set(&lock->locked, 1)) {

// Busy wait - keep spinning

while (lock->locked) {

// Optional: CPU pause instruction for better performance

__asm__ __volatile__("pause" ::: "memory");

}

}

}

void spinlock_release(spinlock_t *lock) {

__sync_lock_release(&lock->locked);

}

Types of Spin Locks

1. Test-and-Set Spin Lock

The simplest form using atomic test-and-set operations:

void simple_spinlock_acquire(volatile int *lock) {

while (__sync_lock_test_and_set(lock, 1)) {

// Spin until lock is acquired

}

}

// Usage example

volatile int my_lock = 0;

simple_spinlock_acquire(&my_lock);

// Critical section

*lock = 0; // Release

2. Test-and-Test-and-Set (TTAS) Spin Lock

An optimized version that reduces memory traffic:

void ttas_spinlock_acquire(volatile int *lock) {

while (1) {

// First test without atomic operation

while (*lock == 1) {

// Spin without generating memory traffic

}

// Then try atomic test-and-set

if (__sync_lock_test_and_set(lock, 1) == 0) {

break; // Successfully acquired

}

}

}

3. Exponential Backoff Spin Lock

Implements delays between attempts to reduce contention:

void backoff_spinlock_acquire(volatile int *lock) {

int delay = 1;

while (__sync_lock_test_and_set(lock, 1)) {

for (int i = 0; i < delay; i++) {

__asm__ __volatile__("pause" ::: "memory");

}

delay = (delay < 1024) ? delay * 2 : delay; // Cap the delay

}

}

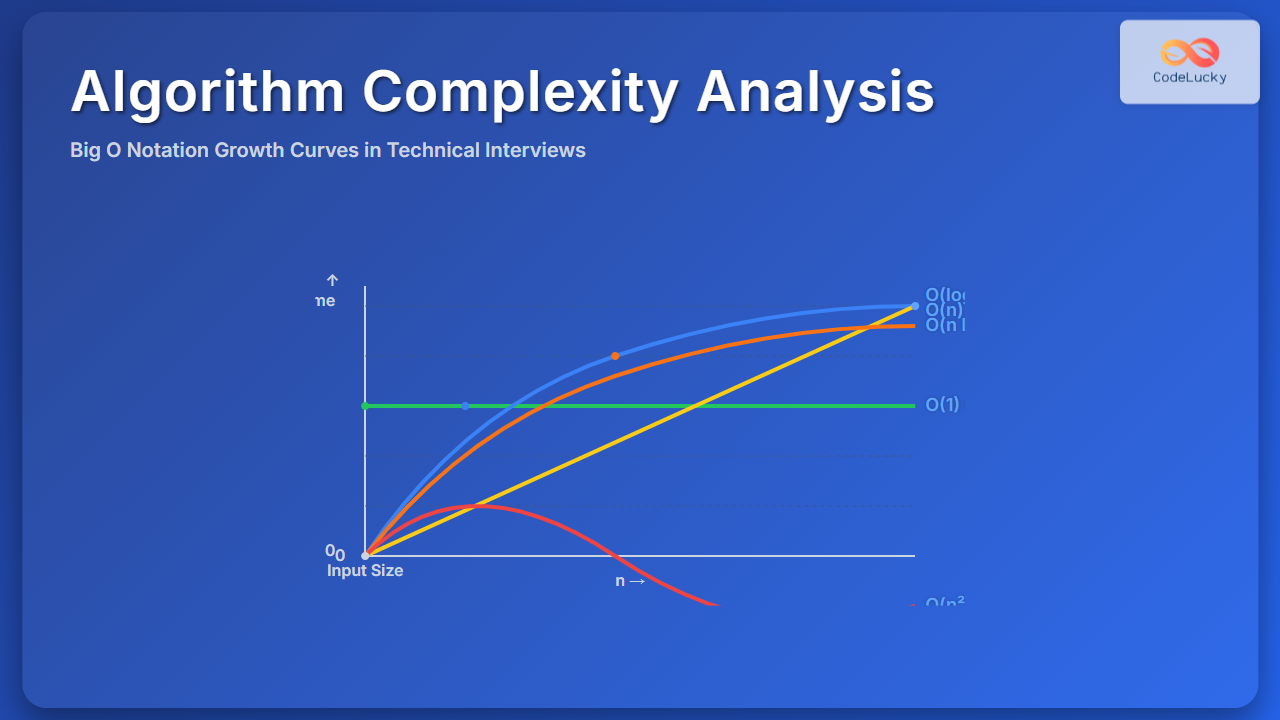

Spin Lock vs Traditional Locks Comparison

| Aspect | Spin Locks | Mutex/Blocking Locks |

|---|---|---|

| CPU Usage | High (continuous polling) | Low (threads sleep) |

| Latency | Very low | Higher (context switching) |

| Best Use Case | Short critical sections | Long critical sections |

| Context Switching | None | Required |

| Memory Overhead | Minimal | Higher (thread queues) |

Real-World Implementation Example

Here’s a complete example demonstrating spin lock usage in a multi-threaded counter scenario:

#include

#include

#include

typedef struct {

atomic_flag locked;

} spinlock_t;

typedef struct {

int counter;

spinlock_t lock;

} shared_data_t;

void spinlock_init(spinlock_t *lock) {

atomic_flag_clear(&lock->locked);

}

void spinlock_lock(spinlock_t *lock) {

while (atomic_flag_test_and_set_explicit(&lock->locked, memory_order_acquire)) {

// Spin wait with CPU pause

__asm__ __volatile__("pause" ::: "memory");

}

}

void spinlock_unlock(spinlock_t *lock) {

atomic_flag_clear_explicit(&lock->locked, memory_order_release);

}

void* worker_thread(void *arg) {

shared_data_t *data = (shared_data_t*)arg;

for (int i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

spinlock_lock(&data->lock);

// Critical section

data->counter++;

spinlock_unlock(&data->lock);

}

return NULL;

}

int main() {

shared_data_t data = {0};

spinlock_init(&data.lock);

pthread_t threads[4];

// Create 4 threads

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

pthread_create(&threads[i], NULL, worker_thread, &data);

}

// Wait for all threads

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

pthread_join(threads[i], NULL);

}

printf("Final counter value: %d\n", data.counter);

// Expected output: Final counter value: 400000

return 0;

}

Performance Characteristics

Memory Traffic Analysis

The performance of spin locks depends heavily on:

- Critical Section Duration: Shorter sections favor spin locks

- Number of Contending Threads: More threads increase spinning overhead

- Cache Coherency: Frequent lock state changes cause cache invalidation

- CPU Architecture: NUMA systems may experience higher latency

Optimization Techniques

// Optimized spin lock with adaptive behavior

typedef struct {

atomic_int locked;

int spin_count;

} adaptive_spinlock_t;

void adaptive_spinlock_acquire(adaptive_spinlock_t *lock) {

int spins = 0;

int max_spins = lock->spin_count;

while (1) {

// Try to acquire immediately

if (atomic_exchange(&lock->locked, 1) == 0) {

lock->spin_count = (spins + lock->spin_count) / 2; // Adapt

return;

}

if (spins++ < max_spins) {

// Continue spinning with backoff

for (int i = 0; i < spins; i++) {

__asm__ __volatile__("pause" ::: "memory");

}

} else {

// Fall back to yielding CPU

sched_yield();

spins = 0;

}

}

}

Use Cases and Applications

1. Kernel-Level Synchronization

Operating system kernels extensively use spin locks for:

- Interrupt handlers (cannot sleep)

- Scheduler data structures

- Memory management routines

- Device driver synchronization

2. High-Performance Applications

// Example: Lock-free queue with spin lock fallback

typedef struct {

volatile int head;

volatile int tail;

spinlock_t resize_lock;

void **buffer;

int capacity;

} spsc_queue_t;

bool queue_enqueue(spsc_queue_t *queue, void *item) {

int current_tail = queue->tail;

int next_tail = (current_tail + 1) % queue->capacity;

if (next_tail == queue->head) {

// Queue full, need resize

spinlock_lock(&queue->resize_lock);

// Resize logic here

spinlock_unlock(&queue->resize_lock);

}

queue->buffer[current_tail] = item;

queue->tail = next_tail;

return true;

}

3. Real-Time Systems

In real-time systems where predictable timing is crucial:

- Avoiding context switch overhead

- Maintaining thread priority levels

- Ensuring bounded execution times

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages

- Low Latency: No context switching overhead

- Simple Implementation: Minimal code complexity

- Predictable Timing: No scheduler interference

- Cache Friendly: Lock variable stays in cache

- Interrupt Safe: Can be used in interrupt contexts

Disadvantages

- CPU Wastage: Consumes cycles while waiting

- Power Consumption: High energy usage on mobile devices

- Scalability Issues: Performance degrades with many threads

- Priority Inversion: Low-priority threads can block high-priority ones

- Unsuitable for Long Waits: Inefficient for lengthy critical sections

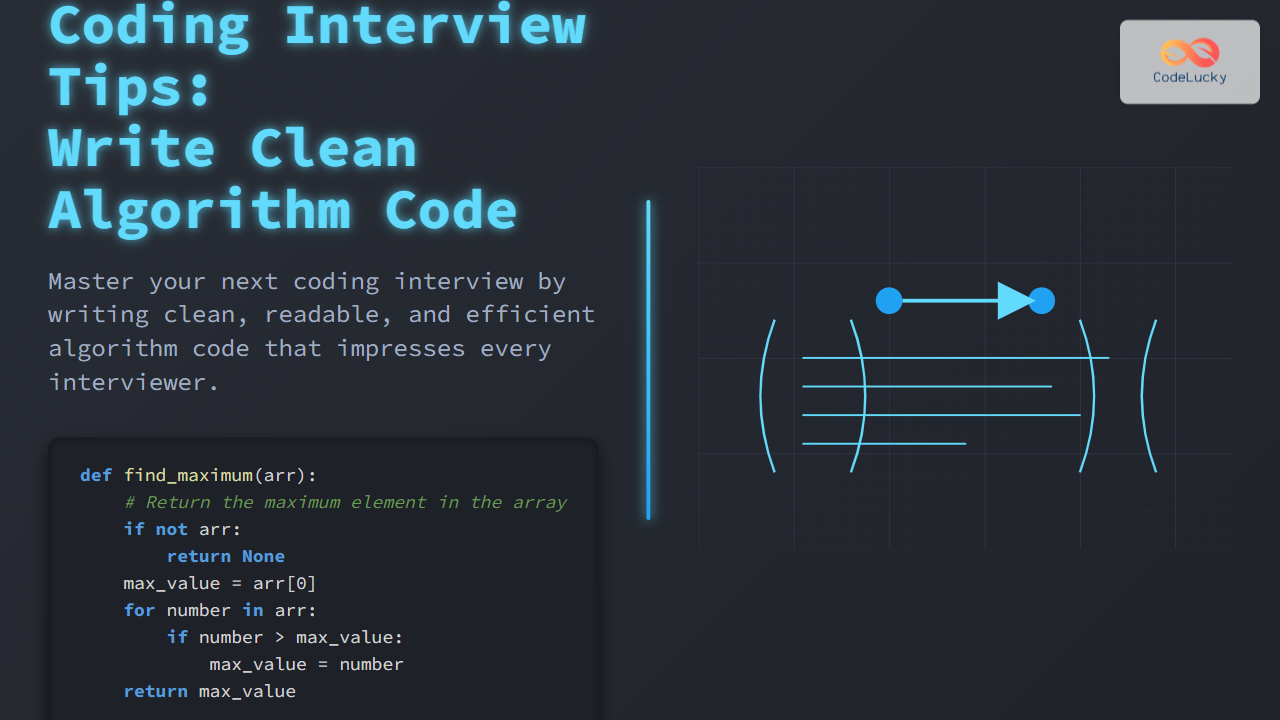

Best Practices and Guidelines

Implementation Guidelines

- Keep Critical Sections Short: Aim for less than 100 CPU cycles

- Limit Thread Count: Don’t exceed the number of CPU cores

- Use Appropriate Memory Barriers: Ensure proper synchronization

- Consider NUMA Topology: Account for memory access patterns

- Profile Performance: Measure actual spinning overhead

// Good practice: Short critical section

spinlock_lock(&cache_lock);

cache_entry->value = new_value; // Fast operation

cache_entry->timestamp = current_time();

spinlock_unlock(&cache_lock);

// Bad practice: Long critical section

spinlock_lock(&file_lock);

result = complex_file_processing(); // Slow I/O operation

write_results_to_disk(result); // Another slow operation

spinlock_unlock(&file_lock);

Alternative Synchronization Mechanisms

When spin locks aren’t suitable, consider these alternatives:

- Mutex Locks: For longer critical sections

- Read-Write Locks: When reads are more frequent than writes

- Semaphores: For resource counting scenarios

- Lock-Free Data Structures: Using atomic operations

- Futex (Fast Userspace Mutex): Hybrid spin-then-block approach

Conclusion

Spin locks are powerful synchronization primitives that excel in specific scenarios requiring low-latency access to shared resources. Their busy-waiting mechanism makes them ideal for short critical sections in kernel code, real-time systems, and high-performance applications. However, their CPU-intensive nature requires careful consideration of use cases, thread counts, and critical section durations.

Understanding when to use spin locks versus traditional blocking mechanisms is crucial for system performance. By following best practices and considering the trade-offs between latency and CPU utilization, developers can effectively leverage spin locks to build efficient concurrent systems.

The key to successful spin lock implementation lies in profiling your specific use case, keeping critical sections minimal, and being aware of the underlying hardware characteristics that influence performance.