Understanding CPU Scheduling in Operating Systems

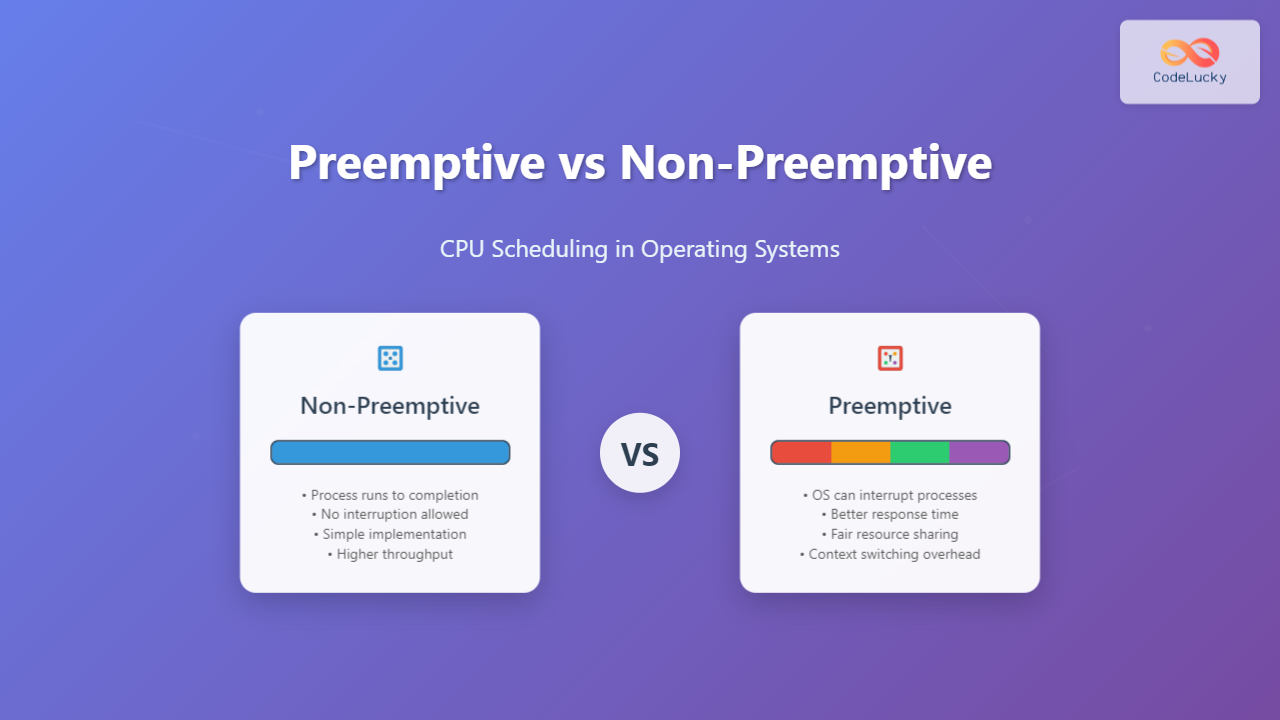

CPU scheduling is one of the most critical functions of an operating system, determining which process gets to execute on the processor at any given time. The scheduler’s primary goal is to maximize CPU utilization while ensuring fair resource allocation among competing processes. Two fundamental approaches govern how operating systems handle process scheduling: preemptive and non-preemptive scheduling.

The choice between these scheduling methods significantly impacts system responsiveness, throughput, and overall user experience. Understanding their differences is crucial for system administrators, developers, and anyone working with operating system internals.

What is Non-Preemptive Scheduling?

Non-preemptive scheduling, also known as cooperative scheduling, allows a running process to complete its execution or voluntarily release the CPU before another process can take control. Once a process begins execution, it continues until one of the following occurs:

- The process completes its execution

- The process voluntarily yields the CPU (system call)

- The process enters a waiting state (I/O operation)

- The process terminates abnormally

Characteristics of Non-Preemptive Scheduling

Non-preemptive scheduling systems exhibit several key characteristics that distinguish them from their preemptive counterparts:

- Process Control: Running processes have complete control over the CPU until they decide to release it

- No Interruption: External events cannot force a process to stop execution midway

- Simple Implementation: Easier to implement due to reduced complexity in context switching

- Predictable Behavior: Process execution times are more predictable as they run to completion

Non-Preemptive Scheduling Algorithms

First Come First Serve (FCFS)

FCFS is the simplest non-preemptive scheduling algorithm where processes are executed in the order they arrive in the ready queue.

Process Arrival Time | Burst Time | Completion Time | Turnaround Time | Waiting Time

P1 0 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0

P2 1 | 4 | 12 | 11 | 7

P3 2 | 9 | 21 | 19 | 10

P4 3 | 5 | 26 | 23 | 18

Average Turnaround Time: (8 + 11 + 19 + 23) / 4 = 15.25 ms

Average Waiting Time: (0 + 7 + 10 + 18) / 4 = 8.75 ms

Shortest Job First (SJF)

SJF selects the process with the smallest burst time for execution. This algorithm is optimal for minimizing average waiting time.

Process Burst Time | Execution Order | Completion Time | Turnaround Time | Waiting Time

P1 6 | 3rd | 16 | 16 | 10

P2 8 | 4th | 24 | 24 | 16

P3 7 | 2nd | 10 | 10 | 3

P4 3 | 1st | 3 | 3 | 0

Average Turnaround Time: (16 + 24 + 10 + 3) / 4 = 13.25 ms

Average Waiting Time: (10 + 16 + 3 + 0) / 4 = 7.25 ms

What is Preemptive Scheduling?

Preemptive scheduling allows the operating system to interrupt a running process and allocate the CPU to another process based on scheduling policies. The scheduler can forcibly remove a process from the CPU at any time, typically triggered by:

- Timer interrupts (time quantum expiration)

- Higher priority process arrival

- System calls or interrupts

- Resource availability changes

Context Switching in Preemptive Systems

Context switching is the mechanism that enables preemptive scheduling. When the scheduler decides to preempt a process, it must:

- Save the current process state: Registers, program counter, stack pointer

- Select the next process: Based on scheduling algorithm

- Restore the new process state: Load saved context from previous execution

- Transfer control: Jump to the appropriate instruction in the new process

// Simplified context switch representation

struct process_context {

int registers[16];

int program_counter;

int stack_pointer;

int process_id;

int priority;

int state;

};

void context_switch(struct process_context *old_process,

struct process_context *new_process) {

// Save current process state

save_registers(old_process->registers);

old_process->program_counter = get_program_counter();

old_process->stack_pointer = get_stack_pointer();

// Load new process state

load_registers(new_process->registers);

set_program_counter(new_process->program_counter);

set_stack_pointer(new_process->stack_pointer);

// Update process states

old_process->state = READY;

new_process->state = RUNNING;

}

Preemptive Scheduling Algorithms

Round Robin (RR)

Round Robin assigns each process a fixed time quantum. When the quantum expires, the process is preempted and moved to the end of the ready queue.

Time Quantum: 3 ms

Process | Burst Time | Execution Timeline | Completion Time | Turnaround Time

P1 | 9 | 0-3, 9-12, 15-18 | 18 | 18

P2 | 6 | 3-6, 12-15 | 15 | 15

P3 | 3 | 6-9 | 9 | 9

Average Turnaround Time: (18 + 15 + 9) / 3 = 14 ms

Context Switches: 5

Shortest Remaining Time First (SRTF)

SRTF is the preemptive version of SJF. It selects the process with the shortest remaining execution time, preempting the current process if a shorter job arrives.

Process | Arrival Time | Burst Time | Start Time | Completion Time | Turnaround

P1 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 17 | 17

P2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 4

P3 | 2 | 9 | 17 | 26 | 24

P4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 7

Execution Order: P1(0-1) → P2(1-5) → P4(5-10) → P1(10-17) → P3(17-26)

Average Turnaround Time: (17 + 4 + 24 + 7) / 4 = 13 ms

Comprehensive Comparison: Preemptive vs Non-Preemptive

| Aspect | Non-Preemptive | Preemptive |

|---|---|---|

| Process Control | Process controls CPU until completion | OS can interrupt process execution |

| Response Time | Higher for interactive systems | Lower, better for real-time systems |

| Context Switching | Minimal overhead | Higher overhead due to frequent switches |

| System Complexity | Simpler implementation | Complex due to interrupt handling |

| Fairness | Poor for CPU-bound processes | Better resource sharing |

| Starvation Risk | High for short processes | Lower with proper algorithms |

| Throughput | Higher due to less overhead | May be lower due to context switching |

Performance Analysis and Trade-offs

Response Time Comparison

The choice between preemptive and non-preemptive scheduling significantly affects system responsiveness. Consider a scenario with mixed workloads:

Workload Mix: 1 CPU-intensive process (100ms) + 4 I/O-intensive processes (5ms each)

Non-Preemptive FCFS:

- CPU process executes first: 0-100ms

- I/O processes wait: 100ms, 105ms, 110ms, 115ms

- Average response time: (0 + 100 + 105 + 110 + 115) / 5 = 86ms

Preemptive Round Robin (Quantum = 10ms):

- All processes get CPU time within first 50ms

- Average response time: (0 + 10 + 20 + 30 + 40) / 5 = 20ms

- 76% improvement in response time

Context Switching Overhead

Context switching introduces measurable overhead that affects overall system performance:

// Typical context switch times on different architectures

Architecture | Context Switch Time | Memory Access Impact

x86-64 | 2-5 microseconds | L1 cache pollution

ARM Cortex-A | 1-3 microseconds | TLB flush required

RISC-V | 1-4 microseconds | Pipeline stall

// Impact on system with 1000 context switches per second

Total overhead = 1000 × 3μs = 3ms per second = 0.3% CPU utilization

Real-World Applications and Use Cases

When to Use Non-Preemptive Scheduling

Batch Processing Systems: Large computational jobs that benefit from uninterrupted execution.

# Example: Scientific computation batch job

#!/bin/bash

# Non-preemptive environment optimal for:

./large_matrix_multiplication input.dat > output.dat

./monte_carlo_simulation 1000000 > results.dat

./data_analysis_pipeline results.dat > final_report.dat

Embedded Systems: Resource-constrained environments where context switching overhead is significant.

Real-time Systems: Deterministic environments where process completion time predictability is crucial.

When to Use Preemptive Scheduling

Interactive Desktop Systems: Multiple applications requiring responsive user interaction.

Server Environments: Handling multiple concurrent requests with varying priorities.

# Example: Web server handling multiple requests

import threading

import time

def handle_request(request_id, processing_time):

"""Simulate request processing with preemptive scheduling"""

print(f"Request {request_id} started at {time.time():.2f}")

# Simulate processing with potential preemption

for chunk in range(processing_time):

time.sleep(0.1) # Allows OS to preempt if needed

print(f"Request {request_id} chunk {chunk} completed")

print(f"Request {request_id} finished at {time.time():.2f}")

# Multiple concurrent requests benefit from preemptive scheduling

threads = []

for i in range(5):

thread = threading.Thread(target=handle_request, args=(i, 10))

threads.append(thread)

thread.start()

for thread in threads:

thread.join()

Modern Operating System Implementations

Linux Kernel Scheduler

Linux uses the Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS), a preemptive scheduler that maintains fairness through virtual runtime tracking:

// Simplified CFS concept

struct task_struct {

u64 vruntime; // Virtual runtime

int nice; // Process priority

struct sched_entity se; // Scheduling entity

};

// CFS selection algorithm (simplified)

struct task_struct *pick_next_task_fair(struct rq *rq) {

struct sched_entity *se = __pick_first_entity(&rq->cfs);

return task_of(se); // Return task with lowest vruntime

}

Windows Task Scheduler

Windows implements a multilevel feedback queue with preemptive priority-based scheduling:

- Priority Levels: 0-31 (0 = lowest, 31 = highest)

- Time Quantum: Varies by priority level and system type

- Priority Boosting: Temporary priority increases for I/O completion

Advanced Scheduling Concepts

Hybrid Scheduling Approaches

Modern systems often combine both approaches based on process characteristics:

Process Classification for Hybrid Scheduling:

CPU-Bound Processes:

- Longer time quantum (non-preemptive behavior)

- Lower context switching frequency

- Examples: Compilers, mathematical computations

I/O-Bound Processes:

- Shorter time quantum (preemptive behavior)

- Higher responsiveness priority

- Examples: Text editors, web browsers

Real-Time Processes:

- Strict deadline-based scheduling

- Preemptive with priority inheritance

- Examples: Audio/video streaming, control systems

Priority Inversion and Solutions

Priority inversion occurs when a high-priority process waits for a low-priority process holding a required resource:

// Priority Inheritance Protocol Implementation

void acquire_mutex(mutex_t *mutex, task_t *task) {

if (mutex->owner && mutex->owner->priority < task->priority) {

// Temporarily boost mutex owner's priority

mutex->owner->inherited_priority = task->priority;

reschedule_task(mutex->owner);

}

// Standard mutex acquisition

lock_mutex(mutex, task);

}

void release_mutex(mutex_t *mutex, task_t *task) {

// Restore original priority

if (task->inherited_priority > task->base_priority) {

task->inherited_priority = task->base_priority;

}

unlock_mutex(mutex);

schedule(); // Trigger rescheduling

}

Performance Optimization Strategies

Minimizing Context Switch Overhead

Several techniques can reduce the performance impact of preemptive scheduling:

- Lazy Context Switching: Defer full context switch until necessary

- CPU Affinity: Keep processes on the same CPU core

- Adaptive Time Quantum: Adjust based on process behavior

# Linux CPU affinity example

# Bind process to specific CPU cores to reduce context switch overhead

taskset -c 0,1 ./cpu_intensive_task

taskset -c 2,3 ./another_cpu_task

# Check current CPU affinity

taskset -p [process_id]

# Set CPU affinity for running process

taskset -cp 0-3 [process_id]

Scheduling Algorithm Selection

Choose scheduling algorithms based on system requirements:

| System Type | Recommended Algorithm | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Interactive Desktop | Preemptive Priority + Round Robin | Good response time for user applications |

| Web Server | Preemptive with Fair Queuing | Equal treatment of client requests |

| Batch Processing | Non-preemptive SJF | Minimizes average completion time |

| Real-time System | Preemptive Priority | Guarantees deadline compliance |

| Mobile Device | Hybrid with Power Awareness | Balances performance and battery life |

Debugging and Monitoring Scheduling Behavior

Linux Tools for Scheduler Analysis

# Monitor context switches per second

sar -w 1 10

# View detailed process scheduling information

cat /proc/[pid]/sched

# Monitor CPU usage by process

top -p [pid] -d 1

# Analyze scheduler latency

perf record -e sched:sched_switch ./your_program

perf report

# Check current scheduling policy

chrt -p [pid]

# Set real-time scheduling policy

chrt -f -p 99 [pid] # FIFO with priority 99

chrt -r -p 50 [pid] # Round Robin with priority 50

Performance Metrics to Monitor

- Context Switch Rate: Number of context switches per second

- CPU Utilization: Percentage of time CPU is busy

- Average Response Time: Time from request to first response

- Throughput: Number of processes completed per unit time

- Waiting Time: Time processes spend in ready queue

Conclusion

The choice between preemptive and non-preemptive scheduling represents a fundamental trade-off in operating system design. Non-preemptive scheduling offers simplicity and efficiency for batch processing and resource-constrained environments, while preemptive scheduling provides the responsiveness and fairness essential for interactive and multi-user systems.

Modern operating systems typically employ sophisticated hybrid approaches that combine the benefits of both paradigms. Understanding these scheduling mechanisms enables system administrators and developers to make informed decisions about process priorities, resource allocation, and performance optimization.

As computing environments continue to evolve with multi-core processors, containerization, and cloud computing, scheduling algorithms must adapt to new challenges while maintaining the core principles of fairness, efficiency, and responsiveness that define effective CPU scheduling.

- Understanding CPU Scheduling in Operating Systems

- What is Non-Preemptive Scheduling?

- What is Preemptive Scheduling?

- Comprehensive Comparison: Preemptive vs Non-Preemptive

- Performance Analysis and Trade-offs

- Real-World Applications and Use Cases

- Modern Operating System Implementations

- Advanced Scheduling Concepts

- Performance Optimization Strategies

- Debugging and Monitoring Scheduling Behavior

- Conclusion