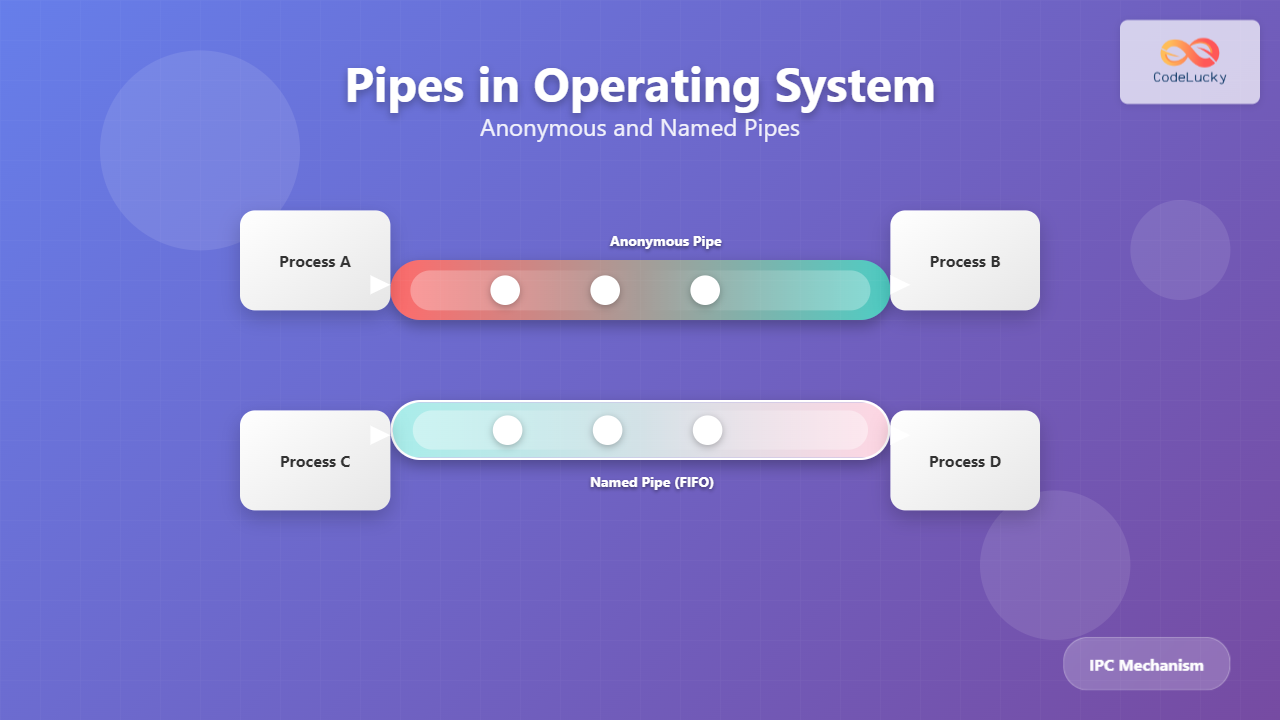

Pipes are one of the most fundamental and widely used Inter-Process Communication (IPC) mechanisms in Unix-like operating systems. They provide a simple yet powerful way for processes to communicate by allowing data to flow from one process to another in a unidirectional manner.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore both anonymous pipes and named pipes, their implementation, use cases, and provide practical examples to help you understand when and how to use each type effectively.

What are Pipes in Operating Systems?

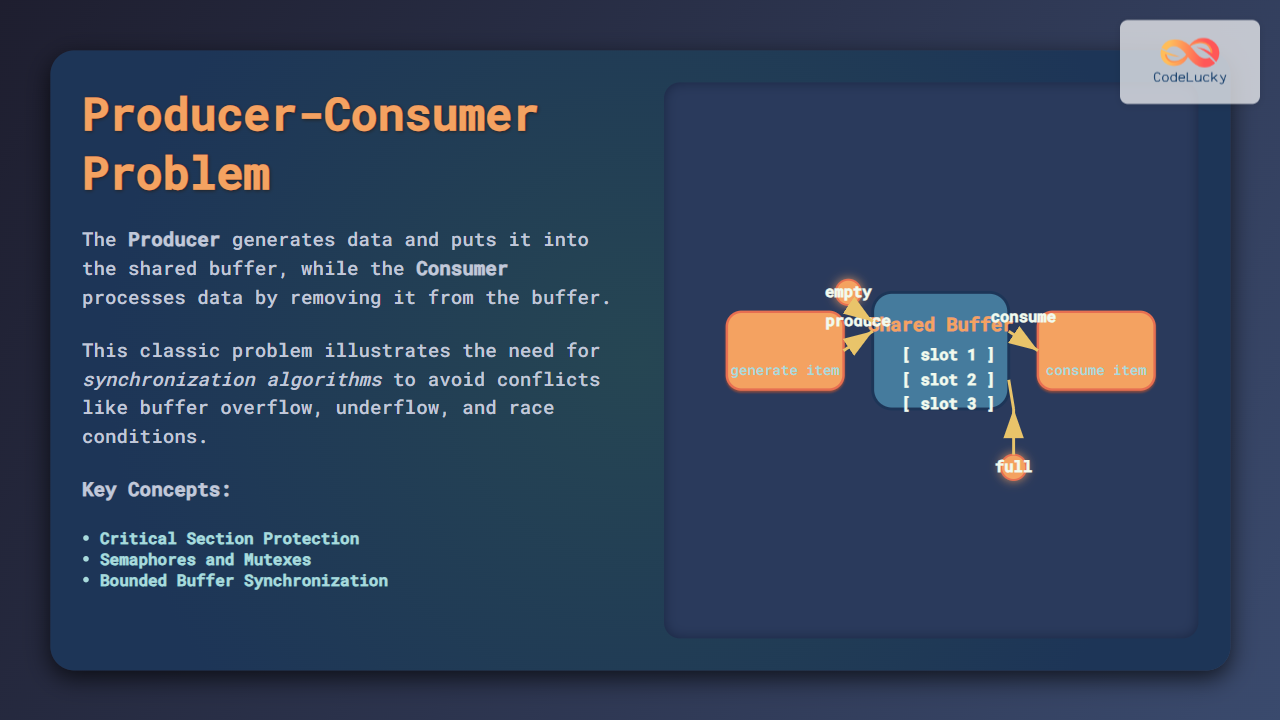

A pipe is a communication channel that connects the output of one process to the input of another process. Think of it as a virtual tube through which data flows from a producer process to a consumer process. Pipes follow the FIFO (First In, First Out) principle, meaning data written first will be read first.

Key Characteristics of Pipes

- Unidirectional: Data flows in only one direction

- Buffered: Operating system provides a buffer to store data temporarily

- Blocking: Read operations block when no data is available; write operations block when buffer is full

- Atomic: Small writes (typically under PIPE_BUF bytes) are atomic

Anonymous Pipes (Unnamed Pipes)

Anonymous pipes are the simplest form of pipes, created using the pipe() system call. They exist only in memory and are automatically destroyed when all processes using them terminate. These pipes can only be used between related processes (parent and child processes).

Creating Anonymous Pipes

Here’s how to create and use anonymous pipes in C:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <string.h>

int main() {

int pipefd[2]; // Array to hold pipe file descriptors

pid_t pid;

char write_msg[] = "Hello from parent process!";

char read_msg[100];

// Create pipe

if (pipe(pipefd) == -1) {

perror("pipe failed");

return 1;

}

// Create child process

pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

// Child process - reader

close(pipefd[1]); // Close write end

// Read from pipe

read(pipefd[0], read_msg, sizeof(read_msg));

printf("Child received: %s\n", read_msg);

close(pipefd[0]); // Close read end

} else {

// Parent process - writer

close(pipefd[0]); // Close read end

// Write to pipe

write(pipefd[1], write_msg, strlen(write_msg) + 1);

printf("Parent sent: %s\n", write_msg);

close(pipefd[1]); // Close write end

wait(NULL); // Wait for child to complete

}

return 0;

}

Output:

Parent sent: Hello from parent process!

Child received: Hello from parent process!

Pipe File Descriptors

The pipe() system call creates two file descriptors:

- pipefd[0]: Read end of the pipe

- pipefd[1]: Write end of the pipe

It’s crucial to close unused ends of the pipe in each process to avoid issues like hanging reads or writes.

Bidirectional Communication with Anonymous Pipes

For bidirectional communication, you need to create two pipes:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

int main() {

int pipe1[2], pipe2[2]; // Two pipes for bidirectional communication

pid_t pid;

char parent_msg[] = "Message from parent";

char child_msg[] = "Message from child";

char buffer[100];

// Create both pipes

if (pipe(pipe1) == -1 || pipe(pipe2) == -1) {

perror("pipe creation failed");

return 1;

}

pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

// Child process

close(pipe1[1]); // Close write end of pipe1

close(pipe2[0]); // Close read end of pipe2

// Read from parent

read(pipe1[0], buffer, sizeof(buffer));

printf("Child received: %s\n", buffer);

// Send response to parent

write(pipe2[1], child_msg, strlen(child_msg) + 1);

close(pipe1[0]);

close(pipe2[1]);

} else {

// Parent process

close(pipe1[0]); // Close read end of pipe1

close(pipe2[1]); // Close write end of pipe2

// Send message to child

write(pipe1[1], parent_msg, strlen(parent_msg) + 1);

// Read response from child

read(pipe2[0], buffer, sizeof(buffer));

printf("Parent received: %s\n", buffer);

close(pipe1[1]);

close(pipe2[0]);

wait(NULL);

}

return 0;

}

Named Pipes (FIFOs)

Named pipes, also called FIFOs (First In, First Out), are a more advanced form of pipes that exist as special files in the filesystem. Unlike anonymous pipes, named pipes can be used for communication between unrelated processes and persist until explicitly deleted.

Creating Named Pipes

Named pipes can be created using the mkfifo() system call or the mkfifo command:

# Command line creation

mkfifo /tmp/mypipe

# Check the created FIFO

ls -l /tmp/mypipe

# Output: prw-rw-r-- 1 user user 0 Aug 28 14:30 /tmp/mypipe

# Note the 'p' at the beginning indicating it's a pipe

Named Pipe Implementation

Writer Process (producer.c):

#include <stdio.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main() {

const char *fifo_path = "/tmp/mypipe";

int fd;

char message[] = "Hello from producer process!";

// Create FIFO if it doesn't exist

mkfifo(fifo_path, 0666);

// Open FIFO for writing

printf("Opening FIFO for writing...\n");

fd = open(fifo_path, O_WRONLY);

if (fd == -1) {

perror("Failed to open FIFO");

return 1;

}

// Write message

printf("Writing: %s\n", message);

write(fd, message, strlen(message) + 1);

close(fd);

printf("Producer finished.\n");

return 0;

}

Reader Process (consumer.c):

#include <stdio.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

const char *fifo_path = "/tmp/mypipe";

int fd;

char buffer[100];

// Open FIFO for reading

printf("Opening FIFO for reading...\n");

fd = open(fifo_path, O_RDONLY);

if (fd == -1) {

perror("Failed to open FIFO");

return 1;

}

// Read message

read(fd, buffer, sizeof(buffer));

printf("Consumer received: %s\n", buffer);

close(fd);

printf("Consumer finished.\n");

return 0;

}

Compilation and Execution:

# Compile both programs

gcc -o producer producer.c

gcc -o consumer consumer.c

# Run consumer in background (it will wait for data)

./consumer &

# Run producer

./producer

# Output:

# Opening FIFO for reading...

# Opening FIFO for writing...

# Writing: Hello from producer process!

# Consumer received: Hello from producer process!

# Producer finished.

# Consumer finished.

Anonymous Pipes vs Named Pipes

| Feature | Anonymous Pipes | Named Pipes (FIFOs) |

|---|---|---|

| Creation | pipe() system call | mkfifo() system call or command |

| Visibility | Only between related processes | Any process with appropriate permissions |

| Persistence | Exists only while processes are running | Persists in filesystem until deleted |

| Location | Memory only | Filesystem entry |

| Use Case | Parent-child communication | Unrelated process communication |

| Performance | Faster (no filesystem overhead) | Slightly slower due to filesystem access |

Advanced Pipe Concepts

Non-blocking Pipes

By default, pipe operations are blocking. You can make them non-blocking using the O_NONBLOCK flag:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <errno.h>

int main() {

int pipefd[2];

char buffer[100];

int flags;

pipe(pipefd);

// Make read end non-blocking

flags = fcntl(pipefd[0], F_GETFL);

fcntl(pipefd[0], F_SETFL, flags | O_NONBLOCK);

// Try to read from empty pipe

if (read(pipefd[0], buffer, sizeof(buffer)) == -1) {

if (errno == EAGAIN) {

printf("No data available - would block\n");

}

}

close(pipefd[0]);

close(pipefd[1]);

return 0;

}

Pipe Capacity and PIPE_BUF

Pipes have a finite capacity (usually 64KB on Linux). The PIPE_BUF constant defines the maximum number of bytes that can be written atomically:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <limits.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

printf("PIPE_BUF: %ld bytes\n", (long)PIPE_BUF);

// Get pipe capacity (Linux-specific)

int pipefd[2];

pipe(pipefd);

long capacity = fpathconf(pipefd[1], _PC_PIPE_BUF);

printf("Pipe buffer size: %ld bytes\n", capacity);

close(pipefd[0]);

close(pipefd[1]);

return 0;

}

Practical Applications and Use Cases

Shell Command Piping

The most common use of pipes is in shell command chaining:

# List files, filter for .txt files, count them

ls -la | grep ".txt" | wc -l

# Find processes and search for specific ones

ps aux | grep "python" | head -5

Producer-Consumer Pattern

Named pipes are excellent for implementing producer-consumer patterns where multiple processes generate and consume data:

// Log aggregator using named pipe

#include <stdio.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <string.h>

// Logger process

void logger_process() {

const char *log_pipe = "/tmp/logpipe";

int fd;

char log_entry[256];

time_t now;

mkfifo(log_pipe, 0666);

while (1) {

fd = open(log_pipe, O_RDONLY);

if (read(fd, log_entry, sizeof(log_entry)) > 0) {

time(&now);

printf("[%s] %s", ctime(&now), log_entry);

}

close(fd);

}

}

// Application sending logs

void send_log(const char *message) {

int fd = open("/tmp/logpipe", O_WRONLY);

write(fd, message, strlen(message));

close(fd);

}

Error Handling and Best Practices

Common Pitfalls and Solutions

- Broken Pipe (SIGPIPE): Occurs when writing to a pipe with no readers

- Deadlocks: Can happen with bidirectional communication if not handled properly

- Buffer Overflow: Writing more data than pipe capacity without proper flow control

#include <signal.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

void handle_sigpipe(int sig) {

printf("Received SIGPIPE - reader has closed the pipe\n");

}

int main() {

// Handle SIGPIPE signal

signal(SIGPIPE, handle_sigpipe);

int pipefd[2];

pipe(pipefd);

// Close read end to simulate broken pipe

close(pipefd[0]);

// This write will generate SIGPIPE

if (write(pipefd[1], "data", 4) == -1) {

perror("Write failed");

}

close(pipefd[1]);

return 0;

}

Best Practices

- Always close unused pipe ends to prevent hanging processes

- Handle SIGPIPE signal appropriately in your applications

- Use error checking for all pipe operations

- Consider buffer sizes and implement flow control for large data transfers

- Clean up named pipes when no longer needed

Performance Considerations

Pipes are highly optimized for local inter-process communication:

- Zero-copy operations: Data is transferred through kernel buffers without unnecessary copying

- Efficient blocking: Processes are suspended efficiently when waiting for data

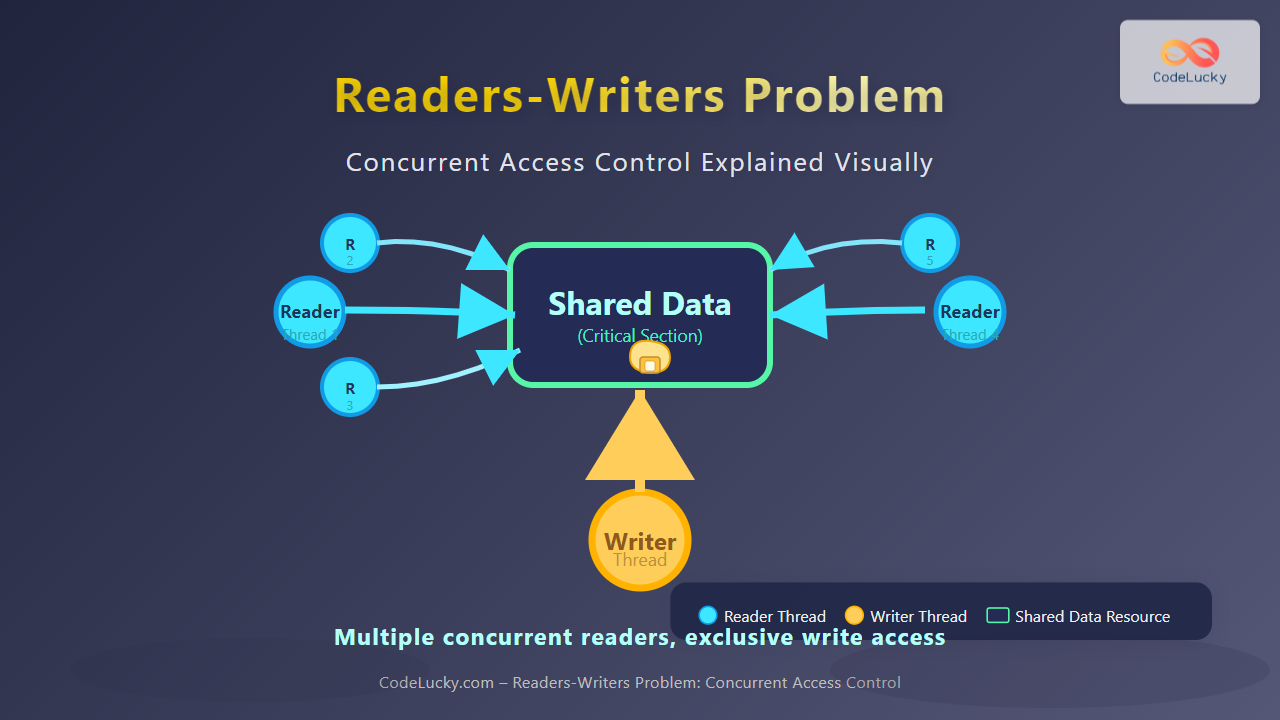

- Automatic synchronization: No need for explicit locking mechanisms

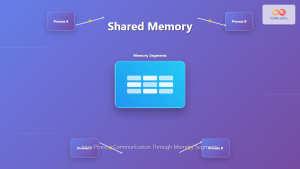

However, for high-throughput applications, consider alternatives like shared memory with semaphores or message queues.

Conclusion

Pipes are fundamental building blocks for inter-process communication in Unix-like systems. Anonymous pipes provide a simple, efficient method for parent-child process communication, while named pipes offer more flexibility for communication between unrelated processes.

Understanding when to use each type of pipe, their limitations, and best practices will help you build robust, efficient applications that leverage the power of process communication. Whether you’re building simple command-line tools or complex multi-process applications, pipes remain an essential tool in the system programmer’s toolkit.

The key to successful pipe implementation lies in proper resource management, error handling, and understanding the blocking nature of pipe operations. With these concepts mastered, you’ll be able to create efficient, communicating processes that form the backbone of many Unix applications.