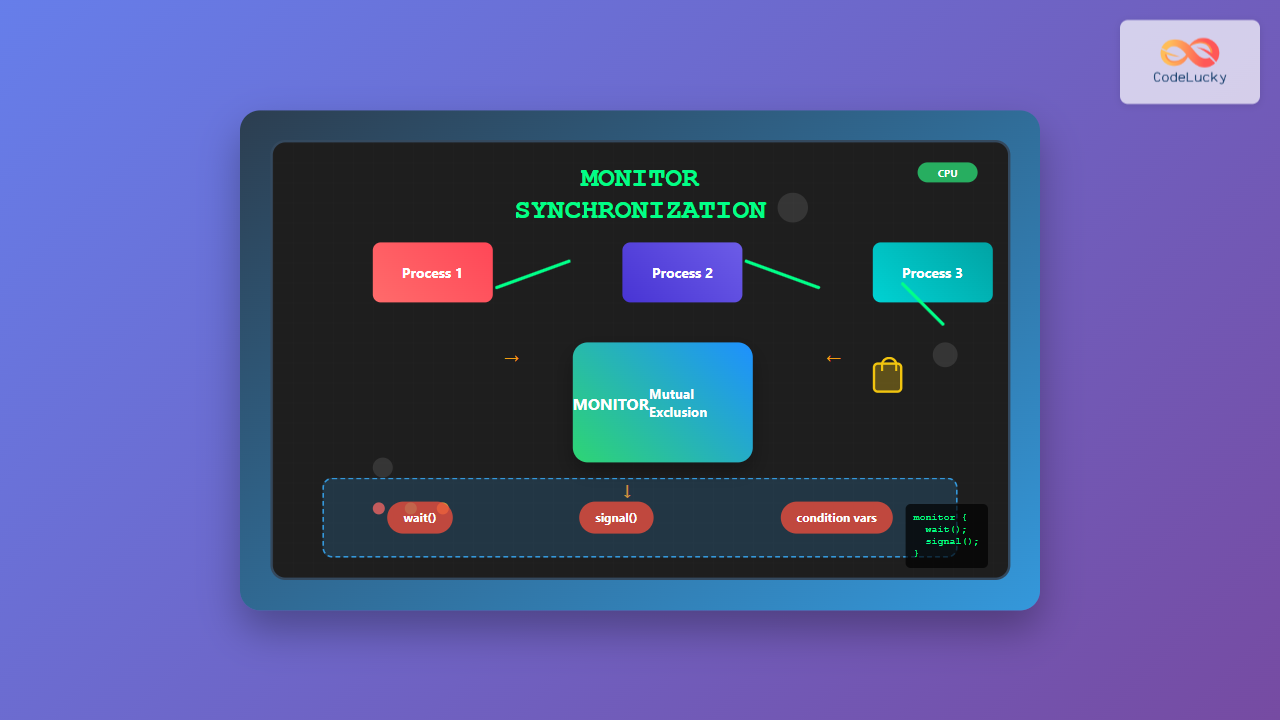

What is a Monitor in Operating System?

A monitor is a high-level synchronization construct in operating systems that provides a structured approach to process synchronization. It encapsulates shared data and the procedures that operate on that data, ensuring that only one process can execute within the monitor at any given time. This mechanism simplifies concurrent programming by automatically handling mutual exclusion and providing condition synchronization.

Monitors were first introduced by C.A.R. Hoare in 1974 as a programming language construct to solve synchronization problems more elegantly than traditional methods like semaphores or mutex locks.

Key Components of a Monitor

A monitor consists of several essential components that work together to provide synchronization:

1. Mutual Exclusion

Only one process can be active within the monitor at any time. This is automatically enforced by the monitor’s implementation, eliminating the need for explicit locking mechanisms.

2. Condition Variables

Special variables that allow processes to wait for certain conditions to become true. They provide two main operations:

wait()– Suspends the calling process and releases the monitor locksignal()– Wakes up one waiting process

3. Shared Data

Variables and data structures that are shared among processes and protected by the monitor.

4. Procedures/Methods

Functions that operate on the shared data and can be called by external processes.

How Monitors Work

The monitor mechanism operates on the following principles:

- Entry Protocol: When a process wants to access the monitor, it must acquire exclusive access

- Execution: The process executes the desired procedure within the monitor

- Condition Checking: If a condition is not met, the process can wait on a condition variable

- Exit Protocol: When the process completes or waits, it releases the monitor lock

Types of Monitor Implementations

1. Hoare Monitors

In Hoare’s original design, when a process signals a condition variable, the signaling process is immediately suspended, and the waiting process is awakened. This ensures that the condition remains true when the waiting process resumes.

// Hoare Monitor Example

monitor BoundedBuffer {

int buffer[N];

int count = 0;

condition notFull, notEmpty;

procedure deposit(item) {

if (count == N)

wait(notFull);

buffer[count++] = item;

signal(notEmpty);

}

procedure remove() {

if (count == 0)

wait(notEmpty);

item = buffer[--count];

signal(notFull);

return item;

}

}

2. Mesa Monitors

In Mesa monitors, when a process signals a condition variable, the signaling process continues execution, and the waiting process is placed in the ready queue. This requires the use of while loops instead of if statements when checking conditions.

// Mesa Monitor Example

monitor BoundedBuffer {

int buffer[N];

int count = 0;

condition notFull, notEmpty;

procedure deposit(item) {

while (count == N)

wait(notFull);

buffer[count++] = item;

signal(notEmpty);

}

procedure remove() {

while (count == 0)

wait(notEmpty);

item = buffer[--count];

signal(notFull);

return item;

}

}

Classic Synchronization Problems Using Monitors

Producer-Consumer Problem

The producer-consumer problem is elegantly solved using monitors. Here’s a complete implementation:

monitor ProducerConsumer {

int buffer[BUFFER_SIZE];

int in = 0, out = 0, count = 0;

condition notFull, notEmpty;

procedure produce(item) {

while (count == BUFFER_SIZE)

wait(notFull);

buffer[in] = item;

in = (in + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

count++;

signal(notEmpty);

}

procedure consume() {

while (count == 0)

wait(notEmpty);

item = buffer[out];

out = (out + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

count--;

signal(notFull);

return item;

}

}

// Producer Process

process Producer {

while (true) {

item = produce_item();

ProducerConsumer.produce(item);

}

}

// Consumer Process

process Consumer {

while (true) {

item = ProducerConsumer.consume();

consume_item(item);

}

}

Readers-Writers Problem

The readers-writers problem can also be solved using monitors:

monitor ReadersWriters {

int readers = 0;

boolean writing = false;

condition okToRead, okToWrite;

procedure startRead() {

while (writing)

wait(okToRead);

readers++;

}

procedure endRead() {

readers--;

if (readers == 0)

signal(okToWrite);

}

procedure startWrite() {

while (readers > 0 || writing)

wait(okToWrite);

writing = true;

}

procedure endWrite() {

writing = false;

signal(okToWrite);

signal(okToRead);

}

}

Advantages of Monitors

- Automatic Mutual Exclusion: No need for explicit lock management

- Structured Approach: Encapsulation of shared data and synchronization logic

- Reduced Errors: Less prone to deadlocks and race conditions

- High-level Abstraction: Easier to understand and maintain than low-level primitives

- Condition Synchronization: Built-in support for waiting on conditions

Disadvantages of Monitors

- Language Support Required: Not all programming languages provide native monitor support

- Performance Overhead: Additional abstraction layer can impact performance

- Limited Flexibility: Less control compared to low-level synchronization primitives

- Potential for Priority Inversion: High-priority processes may wait for low-priority ones

Monitor Implementation in Different Languages

Java Monitors

Java provides built-in monitor support through synchronized methods and blocks:

public class BoundedBuffer {

private int[] buffer;

private int count, in, out;

public BoundedBuffer(int size) {

buffer = new int[size];

count = in = out = 0;

}

public synchronized void put(int item) throws InterruptedException {

while (count == buffer.length)

wait();

buffer[in] = item;

in = (in + 1) % buffer.length;

count++;

notifyAll();

}

public synchronized int get() throws InterruptedException {

while (count == 0)

wait();

int item = buffer[out];

out = (out + 1) % buffer.length;

count--;

notifyAll();

return item;

}

}

C# Monitors

C# provides the Monitor class and lock statement:

public class BoundedBuffer {

private int[] buffer;

private int count, in, out;

private object lockObject = new object();

public void Put(int item) {

lock(lockObject) {

while (count == buffer.Length)

Monitor.Wait(lockObject);

buffer[in] = item;

in = (in + 1) % buffer.Length;

count++;

Monitor.PulseAll(lockObject);

}

}

public int Get() {

lock(lockObject) {

while (count == 0)

Monitor.Wait(lockObject);

int item = buffer[out];

out = (out + 1) % buffer.Length;

count--;

Monitor.PulseAll(lockObject);

return item;

}

}

}

Monitor vs Other Synchronization Mechanisms

| Feature | Monitor | Semaphore | Mutex |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutual Exclusion | Automatic | Manual | Manual |

| Condition Synchronization | Built-in | Complex | Not supported |

| Error Prone | Low | High | Medium |

| Performance | Medium | High | High |

| Abstraction Level | High | Low | Low |

Best Practices for Using Monitors

- Use While Loops: Always use while loops instead of if statements when checking conditions in Mesa-style monitors

- Minimize Monitor Size: Keep monitors small and focused on specific synchronization tasks

- Avoid Nested Monitor Calls: Don’t call one monitor from within another to prevent deadlocks

- Signal at the End: Signal condition variables at the end of procedures when possible

- Use Broadcast Carefully: Use broadcast (notifyAll) sparingly as it can cause unnecessary context switches

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

1. Lost Wake-up Problem

This occurs when a signal is sent before a process is waiting. Always check conditions in loops.

2. Priority Inversion

High-priority processes may wait for low-priority ones. Use priority inheritance protocols when available.

3. Starvation

Some processes may never get access. Implement fair scheduling policies within monitors.

Real-world Applications

Monitors are widely used in:

- Database Systems: Transaction management and resource locking

- Operating System Kernels: Process scheduling and resource allocation

- Web Servers: Connection pool management

- GUI Applications: Event handling and thread synchronization

- Embedded Systems: Real-time task coordination

Conclusion

Monitors provide a powerful and elegant solution for process synchronization in operating systems. They offer automatic mutual exclusion, structured condition synchronization, and reduce the complexity of concurrent programming. While they may have some performance overhead compared to low-level primitives, their benefits in terms of code maintainability, correctness, and reduced development time make them an excellent choice for many synchronization problems.

Understanding monitors is crucial for system programmers and anyone working with concurrent systems. They represent a significant advancement in synchronization techniques and continue to be relevant in modern operating systems and programming languages.