Understanding Memory Protection in Modern Computing

Memory protection is a fundamental security mechanism that prevents programs from accessing memory regions they shouldn’t touch. This critical system feature protects against both accidental bugs and malicious attacks, ensuring system stability and security. Modern operating systems implement memory protection through a combination of hardware features and software policies.

Without proper memory protection, a single faulty program could crash the entire system by overwriting critical operating system data or other applications’ memory spaces. This article explores the intricate mechanisms that prevent such scenarios.

Hardware-Based Memory Protection Mechanisms

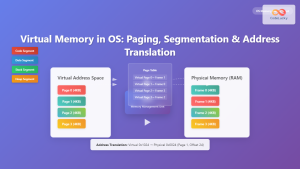

Memory Management Unit (MMU)

The Memory Management Unit (MMU) serves as the primary hardware component responsible for memory protection. It sits between the CPU and physical memory, translating virtual addresses to physical addresses while enforcing access permissions.

Key MMU Functions:

- Address Translation: Converts virtual addresses to physical addresses

- Permission Checking: Validates read, write, and execute permissions

- Page Fault Generation: Triggers exceptions for invalid memory accesses

- TLB Management: Caches recent address translations for performance

Page Tables and Permission Bits

Page tables contain entries that map virtual pages to physical pages, with each entry containing permission bits that define allowed operations:

| Permission Bit | Description | Effect if Set |

|---|---|---|

| Present (P) | Page is in physical memory | Memory access allowed |

| Read/Write (R/W) | Write permission | Page can be modified |

| User/Supervisor (U/S) | User-level access | User programs can access |

| Execute Disable (XD/NX) | Execution prevention | Code execution blocked |

Example: x86-64 Page Table Entry

Bit Layout of Page Table Entry:

63 52 51 12 11 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

[Reserved] [Physical Address] [AVL] [G|P|C|W|U|R|P]

P = Present (1 = page in memory)

R = Read/Write (1 = writable)

U = User/Supervisor (1 = user accessible)

W = Write-Through caching

C = Cache Disable

G = Global page

Hardware Protection Rings

Modern processors implement protection rings (privilege levels) that create hierarchical access control. x86 processors provide four rings (0-3), though most operating systems use only two:

Software-Based Memory Protection Techniques

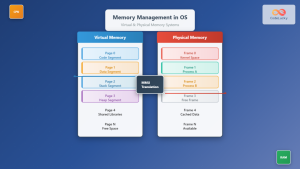

Virtual Memory Management

Operating systems implement sophisticated virtual memory systems that provide each process with its own isolated address space. This isolation is fundamental to memory protection.

Process Address Space Layout:

High Addresses (0xFFFFFFFF)

┌─────────────────────────┐

│ Kernel Space │ ← Protected from user access

├─────────────────────────┤

│ Stack │ ← Grows downward

│ ↓ │

│ │

│ Heap │ ← Grows upward

│ ↑ │

├─────────────────────────┤

│ Data Segment │ ← Global variables

├─────────────────────────┤

│ Text Segment │ ← Program code (read-only)

└─────────────────────────┘

Low Addresses (0x00000000)

Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR)

ASLR randomizes the memory layout of processes, making it difficult for attackers to predict memory addresses. This technique significantly reduces the effectiveness of buffer overflow attacks.

ASLR Implementation Example:

# Check ASLR status on Linux

cat /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

# Output meanings:

# 0 = Disabled

# 1 = Conservative randomization

# 2 = Full randomization (recommended)

# Example memory layout without ASLR:

Process 1: Stack at 0x7fff12345000

Process 2: Stack at 0x7fff12345000 ← Predictable

# Example memory layout with ASLR:

Process 1: Stack at 0x7fff8a2b1000

Process 2: Stack at 0x7fff3f9c8000 ← Randomized

Stack Canaries and Buffer Overflow Protection

Stack canaries are random values placed between local variables and return addresses to detect buffer overflows:

Stack Canary Example:

// Vulnerable function without protection

void vulnerable_function(char *input) {

char buffer[64];

strcpy(buffer, input); // Buffer overflow possible

return;

}

// Protected function with stack canary

void protected_function(char *input) {

// Compiler inserts canary here

char buffer[64];

strcpy(buffer, input);

// Compiler checks canary before return

return; // Abort if canary corrupted

}

Memory Protection in Practice

Segmentation vs. Paging

Two primary approaches exist for implementing memory protection:

| Aspect | Segmentation | Paging |

|---|---|---|

| Granularity | Variable-sized segments | Fixed-sized pages (4KB typical) |

| Protection | Per-segment permissions | Per-page permissions |

| Fragmentation | External fragmentation | Internal fragmentation |

| Modern Usage | Limited (x86 legacy) | Dominant approach |

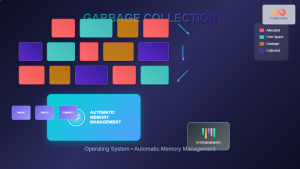

Copy-on-Write (COW) Protection

Copy-on-Write is an optimization technique that provides memory protection while reducing memory usage. When processes fork, they initially share the same physical memory pages marked as read-only.

COW Implementation Example:

# Demonstrating COW behavior

pid = fork()

if pid == 0: # Child process

# Initially shares parent's memory

data = "shared_data"

# This triggers COW - page copied

data = "modified_data"

else: # Parent process

# Parent still has original data

data = "shared_data"

Execute Disable (XD) and No-Execute (NX)

Modern processors support Execute Disable bits that prevent code execution from data pages, effectively blocking many code injection attacks:

// Memory region types and their typical permissions

Text Segment: Read + Execute (no write)

Data Segment: Read + Write (no execute)

Stack: Read + Write (no execute with NX)

Heap: Read + Write (no execute with NX)

// Example: Attempting to execute code from stack

void vulnerable() {

char shellcode[] = "\x48\x31\xc0..."; // Machine code

((void(*)())shellcode)(); // Fails with NX bit set

}

// Result with NX protection:

// Segmentation fault (SIGSEGV) - attempted execution from non-executable page

Advanced Memory Protection Features

Control Flow Integrity (CFI)

CFI ensures that program execution follows legitimate control flow paths, preventing attacks that hijack program execution:

- Forward-Edge CFI: Protects function calls and jumps

- Backward-Edge CFI: Protects return addresses

- Hardware Support: Intel CET, ARM Pointer Authentication

Memory Tagging and Bounds Checking

Emerging technologies provide fine-grained memory safety:

| Technology | Description | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| ARM MTE | Memory Tagging Extension | 4-bit tags per 16-byte granule |

| Intel MPX | Memory Protection Extensions | Hardware bounds checking |

| CHERI | Capability Hardware | Fine-grained capabilities |

Memory Tagging Example:

// Conceptual memory tagging

void *ptr = malloc(1024); // Allocate with tag 0x5

*((char*)ptr + 1023) = 'A'; // Valid access (within bounds)

*((char*)ptr + 1024) = 'B'; // Tag mismatch - bounds violation detected

// Hardware automatically checks:

// - Pointer tag matches memory tag

// - Access within allocated bounds

// - Generates exception on violation

Memory Protection Violations and Handling

Common Protection Violations

Understanding common memory protection violations helps in debugging and security analysis:

Violation Examples:

// 1. Write to read-only memory

char *text = "Hello World";

text[0] = 'h'; // Segmentation fault - text segment is read-only

// 2. Execute data as code

char data[] = {0x90, 0x90, 0x90}; // NOP instructions

((void(*)())data)(); // Segmentation fault - data not executable

// 3. Access kernel memory from user space

char *kernel_addr = (char*)0xFFFFFFFF80000000;

*kernel_addr = 0x42; // Segmentation fault - kernel space protected

// 4. Stack overflow

void recursive_function() {

char large_array[1000000];

recursive_function(); // Stack overflow - guard page violation

}

Debugging Memory Protection Issues

Tools and techniques for investigating memory protection violations:

# Using GDB to analyze segmentation faults

gdb ./program core

(gdb) bt # Show stack trace

(gdb) info registers # Check register values

(gdb) x/10i $pc # Examine instructions at crash

# Using valgrind for memory error detection

valgrind --tool=memcheck ./program

# Output example:

==12345== Invalid write of size 1

==12345== at 0x40056B: main (test.c:10)

==12345== Address 0x4008c0 is not stack'd, malloc'd or free'd

# Checking memory maps

cat /proc/PID/maps

# Shows virtual memory layout and permissions

Performance Impact and Optimization

TLB Performance Considerations

Memory protection mechanisms can impact performance, particularly through TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer) misses:

- TLB Hit: Address translation cached, ~1 CPU cycle

- TLB Miss: Page table walk required, ~100+ CPU cycles

- Optimization: Large pages reduce TLB pressure

TLB Optimization Example:

# Check TLB statistics

perf stat -e dTLB-loads,dTLB-load-misses,iTLB-loads,iTLB-load-misses ./program

# Enable huge pages for better TLB efficiency

echo always > /sys/kernel/mm/transparent_hugepage/enabled

# Application can request huge pages

mmap(NULL, 2*1024*1024, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS|MAP_HUGETLB, -1, 0);

Future of Memory Protection

Emerging trends in memory protection technology include:

- Hardware Capabilities: CHERI and similar capability-based systems

- AI-Assisted Protection: Machine learning for anomaly detection

- Quantum-Resistant Security: Post-quantum cryptographic protections

- Real-Time Protection: Low-latency security for embedded systems

Memory protection remains a cornerstone of system security, continuously evolving to address new threats while maintaining system performance. The combination of hardware features like MMUs and NX bits with software techniques like ASLR and stack canaries provides robust defense against memory-based attacks.

Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for system programmers, security researchers, and anyone working with low-level system software. As computing environments become more complex and security threats more sophisticated, memory protection mechanisms will continue to advance, providing stronger guarantees while minimizing performance overhead.

- Understanding Memory Protection in Modern Computing

- Hardware-Based Memory Protection Mechanisms

- Software-Based Memory Protection Techniques

- Memory Protection in Practice

- Advanced Memory Protection Features

- Memory Protection Violations and Handling

- Performance Impact and Optimization

- Future of Memory Protection