Memory allocation is a fundamental aspect of operating system design that determines how programs and data are stored and accessed in computer memory. Understanding the different allocation techniques is crucial for system administrators, developers, and anyone working with system-level programming.

What is Memory Allocation?

Memory allocation refers to the process of assigning portions of physical memory (RAM) to running processes and programs. The operating system’s memory manager is responsible for tracking which memory locations are free, which are occupied, and efficiently distributing available memory among competing processes.

The choice of memory allocation technique directly impacts system performance, memory utilization efficiency, and the complexity of memory management operations. Modern operating systems employ sophisticated algorithms to balance these factors while ensuring system stability and optimal resource usage.

Types of Memory Allocation Techniques

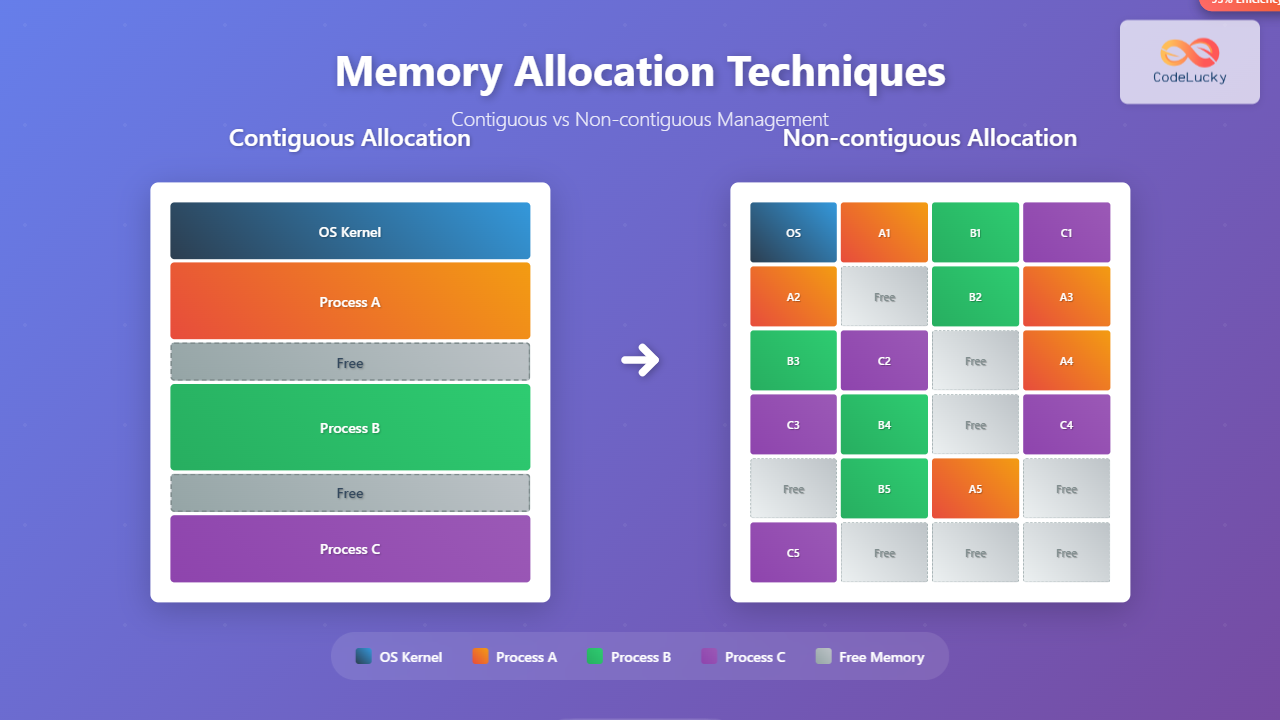

Memory allocation techniques are broadly categorized into two main approaches:

- Contiguous Memory Allocation – Allocates consecutive memory blocks

- Non-contiguous Memory Allocation – Allows scattered memory block allocation

Contiguous Memory Allocation

Contiguous memory allocation assigns consecutive memory addresses to a process. This means all memory locations allocated to a program are adjacent to each other in physical memory, creating a single continuous block.

Characteristics of Contiguous Allocation

- Simple memory management with minimal overhead

- Fast access due to locality of reference

- Easy implementation of memory protection

- Direct mapping between logical and physical addresses

- Susceptible to external fragmentation

Types of Contiguous Allocation Strategies

1. Fixed Partitioning

Memory is divided into fixed-size partitions at system startup. Each process is allocated to a partition that can accommodate its size requirements.

Memory Layout Example:

┌─────────────────┐ 0KB

│ OS Kernel │

├─────────────────┤ 100KB

│ Partition 1 │ (200KB)

├─────────────────┤ 300KB

│ Partition 2 │ (200KB)

├─────────────────┤ 500KB

│ Partition 3 │ (300KB)

├─────────────────┤ 800KB

│ Partition 4 │ (200KB)

└─────────────────┘ 1000KBAdvantages:

- Simple implementation and management

- Fast allocation and deallocation

- No external fragmentation

Disadvantages:

- Internal fragmentation when process size < partition size

- Limited number of concurrent processes

- Poor memory utilization

2. Dynamic Partitioning

Partitions are created dynamically based on process requirements. The system allocates exactly the amount of memory requested by each process.

Initial State:

┌─────────────────┐ 0KB

│ OS Kernel │

├─────────────────┤ 100KB

│ │

│ Free Memory │

│ │

└─────────────────┘ 1000KB

After Process Allocation:

┌─────────────────┐ 0KB

│ OS Kernel │

├─────────────────┤ 100KB

│ Process A │ (150KB)

├─────────────────┤ 250KB

│ Process B │ (200KB)

├─────────────────┤ 450KB

│ Free Memory │

└─────────────────┘ 1000KBAllocation Algorithms for Dynamic Partitioning

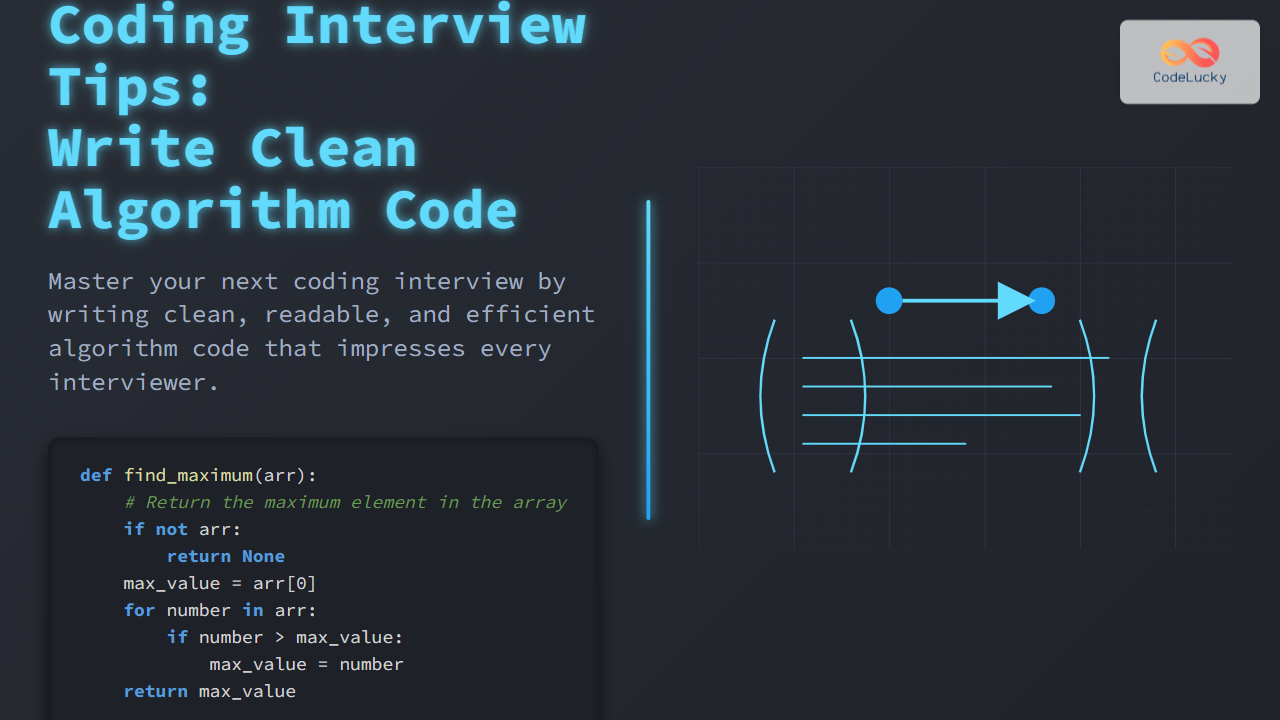

First Fit Algorithm

Allocates the first available free block that is large enough to accommodate the process.

def first_fit(memory_blocks, process_size):

for i, block in enumerate(memory_blocks):

if block['free'] and block['size'] >= process_size:

# Allocate memory

block['free'] = False

block['process'] = current_process

return block['start_address']

return None # No suitable block foundBest Fit Algorithm

Searches for the smallest free block that can accommodate the process, minimizing wasted space.

def best_fit(memory_blocks, process_size):

best_block = None

min_waste = float('inf')

for block in memory_blocks:

if block['free'] and block['size'] >= process_size:

waste = block['size'] - process_size

if waste < min_waste:

min_waste = waste

best_block = block

if best_block:

best_block['free'] = False

best_block['process'] = current_process

return best_block['start_address']

return NoneWorst Fit Algorithm

Allocates the largest available free block, leaving the maximum remaining free space.

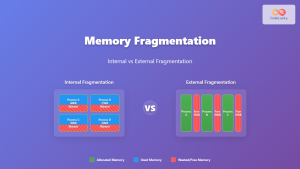

Memory Compaction

To address external fragmentation in dynamic partitioning, operating systems use memory compaction – relocating allocated partitions to create larger contiguous free spaces.

Non-contiguous Memory Allocation

Non-contiguous memory allocation allows a process to occupy multiple non-adjacent memory blocks. This approach eliminates the requirement for consecutive memory addresses, providing greater flexibility in memory management.

Advantages of Non-contiguous Allocation

- Eliminates external fragmentation

- Better memory utilization

- Supports virtual memory implementation

- Allows processes larger than available contiguous memory

- Facilitates memory sharing between processes

Disadvantages of Non-contiguous Allocation

- Complex memory management overhead

- Address translation complexity

- Potential for internal fragmentation

- Hardware support requirements

Paging – A Non-contiguous Technique

Paging divides physical memory into fixed-size blocks called frames and logical memory into blocks of the same size called pages. The operating system maintains a page table to map logical pages to physical frames.

Paging Implementation

Page Table Structure

Page Table Example (4KB pages):

┌─────────────┬─────────────┬─────────────┐

│ Page Number │ Frame Number│ Valid Bit │

├─────────────┼─────────────┼─────────────┤

│ 0 │ 5 │ 1 │

│ 1 │ 2 │ 1 │

│ 2 │ 8 │ 1 │

│ 3 │ 1 │ 1 │

│ 4 │ - │ 0 │

└─────────────┴─────────────┴─────────────┘Address Translation in Paging

The memory management unit (MMU) translates logical addresses to physical addresses using the following process:

- Extract page number from the logical address

- Look up frame number in the page table

- Combine frame number with page offset to form physical address

Address Translation Example:

Logical Address: 8196 (binary: 10000000000100)

Page Size: 4KB (4096 bytes)

Page Number = 8196 / 4096 = 2

Page Offset = 8196 % 4096 = 4

From Page Table: Page 2 → Frame 8

Physical Address = (Frame 8 × 4096) + 4 = 32772Multi-level Paging

For systems with large address spaces, single-level page tables become impractically large. Multi-level paging breaks the page table into smaller, manageable pieces.

Segmentation – Another Non-contiguous Approach

Segmentation divides programs into logical segments such as code, data, and stack. Each segment can vary in size and is allocated non-contiguously in memory.

Segment Table Structure

Segment Table:

┌─────────────┬─────────────┬─────────────┬─────────────┐

│ Segment # │ Base Address│ Limit │ Permissions │

├─────────────┼─────────────┼─────────────┼─────────────┤

│ 0 │ 1000 │ 500 │ R-X │ Code

│ 1 │ 2000 │ 300 │ RW- │ Data

│ 2 │ 3500 │ 200 │ RW- │ Stack

│ 3 │ 4000 │ 150 │ R-- │ Constants

└─────────────┴─────────────┴─────────────┴─────────────┘Segmented Paging

Many modern systems combine segmentation and paging to leverage benefits of both techniques. Each segment is divided into pages, providing both logical organization and efficient memory utilization.

Comparison: Contiguous vs Non-contiguous Allocation

| Aspect | Contiguous Allocation | Non-contiguous Allocation |

|---|---|---|

| Memory Utilization | Lower due to fragmentation | Higher, better space efficiency |

| Implementation Complexity | Simple and straightforward | Complex with hardware support |

| Address Translation | Direct, minimal overhead | Requires translation tables |

| External Fragmentation | Significant problem | Eliminated completely |

| Internal Fragmentation | Possible in fixed partitioning | Minimal in paging systems |

| Memory Protection | Simple base-limit registers | Page-level protection bits |

| Virtual Memory Support | Limited or impossible | Full virtual memory support |

| Process Size Limitations | Limited by largest free block | Can exceed physical memory |

Performance Considerations

Memory Access Patterns

The choice between contiguous and non-contiguous allocation significantly impacts system performance based on memory access patterns:

- Sequential Access: Contiguous allocation provides better cache performance

- Random Access: Non-contiguous allocation offers more flexibility

- Large Data Sets: Non-contiguous allocation prevents memory starvation

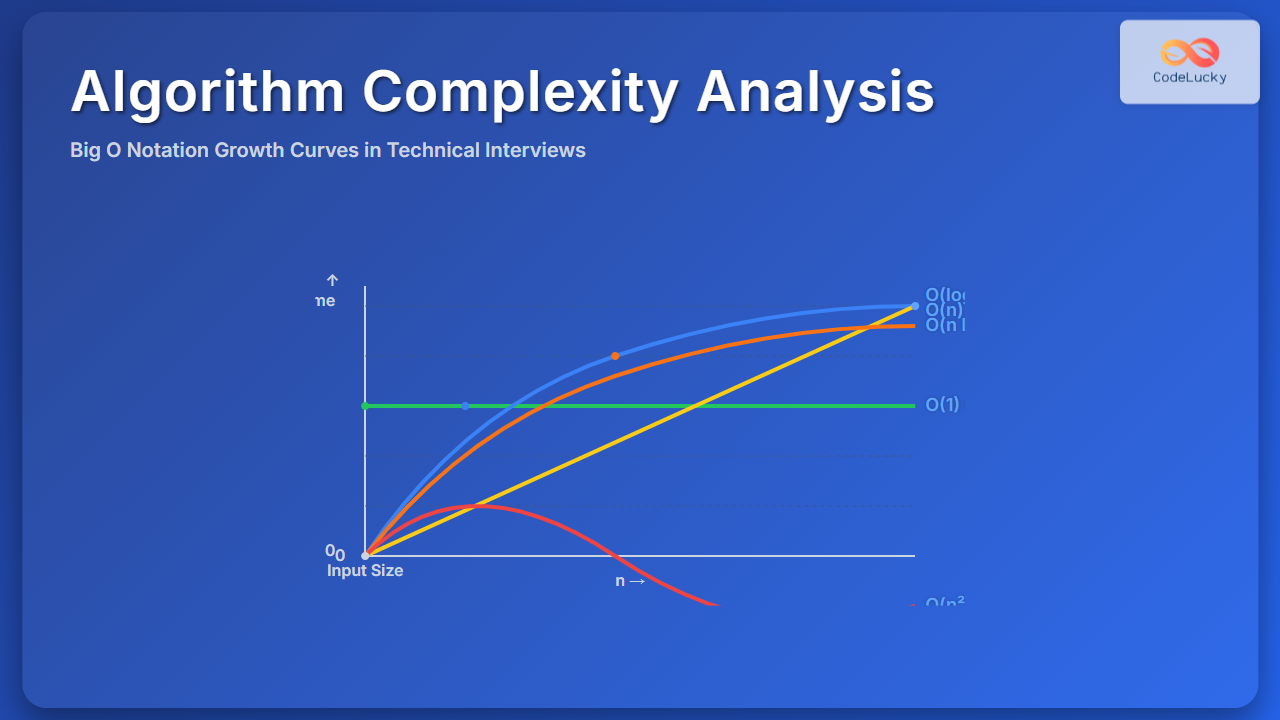

Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

In non-contiguous systems, the TLB caches recent address translations to reduce the overhead of page table lookups:

TLB Hit Rate Impact:

- TLB Hit: ~1 cycle access time

- TLB Miss: ~100+ cycles (page table walk)

- Effective Access Time = Hit Rate × Hit Time + Miss Rate × Miss TimeModern Memory Management Trends

Hybrid Approaches

Contemporary operating systems often employ hybrid strategies combining multiple allocation techniques:

- Kernel Space: Often uses contiguous allocation for critical data structures

- User Space: Primarily uses paging for process memory

- Device Drivers: May require contiguous memory for DMA operations

- File Systems: Use both approaches depending on file size and access patterns

Large Page Support

Modern processors support multiple page sizes (4KB, 2MB, 1GB) to reduce TLB pressure for large applications while maintaining granular control for smaller allocations.

Implementation Examples

Simple Memory Allocator

class MemoryAllocator:

def __init__(self, total_memory):

self.memory_blocks = [

{'start': 0, 'size': total_memory, 'free': True, 'process': None}

]

def allocate(self, process_id, size, algorithm='first_fit'):

if algorithm == 'first_fit':

return self._first_fit(process_id, size)

elif algorithm == 'best_fit':

return self._best_fit(process_id, size)

return None

def deallocate(self, process_id):

for block in self.memory_blocks:

if block['process'] == process_id:

block['free'] = True

block['process'] = None

self._coalesce() # Merge adjacent free blocks

def _first_fit(self, process_id, size):

for i, block in enumerate(self.memory_blocks):

if block['free'] and block['size'] >= size:

self._split_block(i, size, process_id)

return block['start']

return NonePage Table Implementation

class PageTable:

def __init__(self, page_size=4096):

self.page_size = page_size

self.entries = {} # page_number -> frame_number

def map_page(self, page_number, frame_number):

self.entries[page_number] = {

'frame': frame_number,

'valid': True,

'dirty': False,

'referenced': False

}

def translate_address(self, logical_address):

page_number = logical_address // self.page_size

page_offset = logical_address % self.page_size

if page_number not in self.entries or not self.entries[page_number]['valid']:

raise PageFaultException(f"Page {page_number} not in memory")

frame_number = self.entries[page_number]['frame']

physical_address = (frame_number * self.page_size) + page_offset

# Update reference bit for LRU replacement

self.entries[page_number]['referenced'] = True

return physical_addressBest Practices and Recommendations

When to Use Contiguous Allocation

- Real-time systems requiring predictable memory access

- Embedded systems with limited hardware capabilities

- Device driver development for DMA operations

- High-performance computing applications with sequential access patterns

When to Use Non-contiguous Allocation

- General-purpose operating systems

- Multi-user environments with varying process sizes

- Systems requiring virtual memory support

- Applications with unpredictable memory access patterns

Optimization Strategies

- Memory Pool Allocation: Pre-allocate fixed-size blocks for frequent allocations

- Buddy System: Combine benefits of both approaches for efficient allocation

- NUMA Awareness: Consider processor-memory topology in allocation decisions

- Huge Page Usage: Leverage large pages for memory-intensive applications

Understanding memory allocation techniques is essential for developing efficient systems and applications. While contiguous allocation offers simplicity and performance benefits in specific scenarios, non-contiguous allocation provides the flexibility and efficiency required by modern computing environments. The choice between these approaches depends on specific system requirements, hardware constraints, and performance objectives.

As computing systems continue evolving, hybrid approaches that intelligently combine multiple allocation strategies are becoming increasingly prevalent, offering the benefits of both contiguous and non-contiguous techniques while minimizing their respective drawbacks.