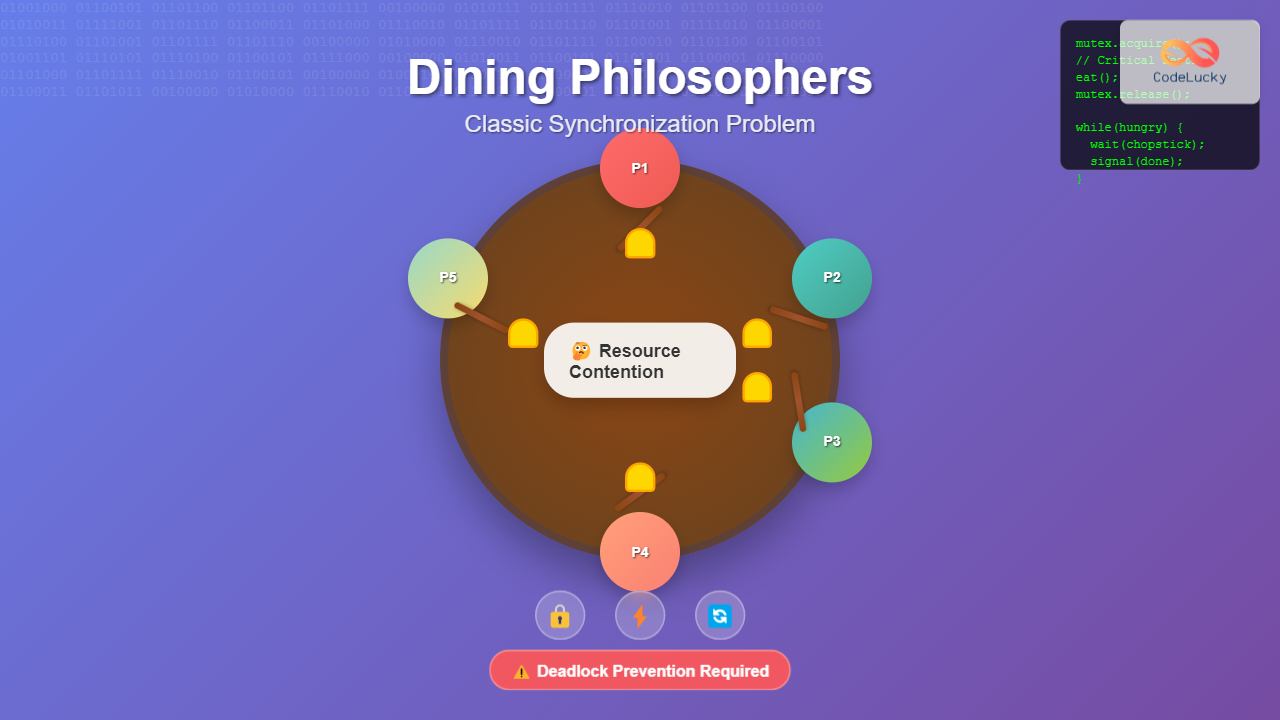

The Dining Philosophers Problem stands as one of the most iconic examples in computer science for understanding synchronization challenges in concurrent programming. Originally formulated by Edsger Dijkstra in 1965, this thought experiment elegantly illustrates the complexities of resource allocation, deadlock prevention, and process synchronization in operating systems.

What is the Dining Philosophers Problem?

The Dining Philosophers Problem presents a scenario where five philosophers sit around a circular dining table. Each philosopher alternates between two activities: thinking and eating. To eat, a philosopher needs both chopsticks (or forks) that are placed between adjacent philosophers. The challenge lies in designing a synchronization mechanism that allows all philosophers to eat without causing deadlock, starvation, or resource conflicts.

Core Components and Rules

The Philosophers

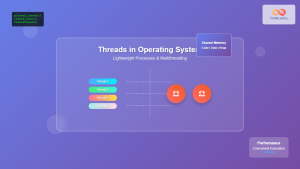

- Five philosophers represent concurrent processes or threads

- Each philosopher has two states: thinking and eating

- Philosophers think for a random amount of time

- When hungry, they attempt to acquire resources (chopsticks) to eat

The Chopsticks (Resources)

- Five chopsticks represent shared resources

- Each chopstick can be held by only one philosopher at a time

- A philosopher needs both adjacent chopsticks to eat

- Chopsticks must be released after eating

Fundamental Rules

- A philosopher can only eat when holding both adjacent chopsticks

- Chopsticks cannot be shared simultaneously

- A philosopher must release both chopsticks after eating

- The process continues indefinitely

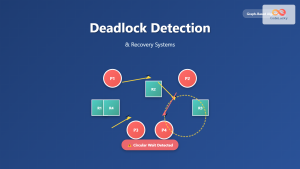

The Deadlock Problem

The most critical issue in the Dining Philosophers Problem is deadlock. This occurs when all philosophers simultaneously pick up their left chopstick and wait indefinitely for their right chopstick, which is already held by their neighbor.

Deadlock Conditions

The dining philosophers scenario satisfies all four Coffman conditions for deadlock:

- Mutual Exclusion: Only one philosopher can hold a chopstick

- Hold and Wait: Philosophers hold one chopstick while waiting for another

- No Preemption: Chopsticks cannot be forcibly taken away

- Circular Wait: Each philosopher waits for their neighbor’s chopstick

Naive Solution and Its Problems

A straightforward approach might look like this:

class Philosopher:

def __init__(self, id, left_chopstick, right_chopstick):

self.id = id

self.left_chopstick = left_chopstick

self.right_chopstick = right_chopstick

def eat(self):

# Naive approach - PRONE TO DEADLOCK

self.left_chopstick.acquire() # Pick up left chopstick

self.right_chopstick.acquire() # Pick up right chopstick

print(f"Philosopher {self.id} is eating")

time.sleep(random.uniform(1, 3)) # Eating time

self.right_chopstick.release() # Put down right chopstick

self.left_chopstick.release() # Put down left chopstick

Problem: If all philosophers simultaneously execute left_chopstick.acquire(), they’ll all wait indefinitely for their right chopstick, creating a deadlock.

Classical Solutions

1. Asymmetric Solution

The most elegant solution breaks the circular wait by making one philosopher pick up chopsticks in reverse order:

import threading

import time

import random

class DiningPhilosophers:

def __init__(self):

self.chopsticks = [threading.Lock() for _ in range(5)]

self.philosophers = []

def philosopher(self, id):

left = id

right = (id + 1) % 5

while True:

self.think(id)

# Asymmetric solution: philosopher 0 picks up in reverse order

if id == 0:

first, second = right, left

else:

first, second = left, right

# Acquire chopsticks in determined order

self.chopsticks[first].acquire()

self.chopsticks[second].acquire()

self.eat(id)

# Release chopsticks

self.chopsticks[second].release()

self.chopsticks[first].release()

def think(self, id):

print(f"Philosopher {id} is thinking")

time.sleep(random.uniform(1, 3))

def eat(self, id):

print(f"Philosopher {id} is eating")

time.sleep(random.uniform(1, 2))

# Usage

dining = DiningPhilosophers()

threads = []

for i in range(5):

t = threading.Thread(target=dining.philosopher, args=(i,))

threads.append(t)

t.start()

2. Semaphore Solution

Another approach uses a semaphore to limit the number of philosophers that can attempt to eat simultaneously:

import threading

import time

import random

class DiningPhilosophersSemaphore:

def __init__(self):

self.chopsticks = [threading.Lock() for _ in range(5)]

# Allow only 4 philosophers to compete for chopsticks

self.eating_semaphore = threading.Semaphore(4)

def philosopher(self, id):

left = id

right = (id + 1) % 5

while True:

self.think(id)

# Wait for permission to attempt eating

self.eating_semaphore.acquire()

# Acquire chopsticks

self.chopsticks[left].acquire()

self.chopsticks[right].acquire()

self.eat(id)

# Release chopsticks

self.chopsticks[right].release()

self.chopsticks[left].release()

# Release eating permission

self.eating_semaphore.release()

def think(self, id):

print(f"Philosopher {id} is thinking")

time.sleep(random.uniform(1, 3))

def eat(self, id):

print(f"Philosopher {id} is eating")

time.sleep(random.uniform(1, 2))

3. Monitor Solution

A more sophisticated approach uses monitors with condition variables:

import threading

import time

import random

from enum import Enum

class State(Enum):

THINKING = 1

HUNGRY = 2

EATING = 3

class DiningPhilosophersMonitor:

def __init__(self):

self.state = [State.THINKING] * 5

self.condition = [threading.Condition() for _ in range(5)]

self.lock = threading.Lock()

def philosopher(self, id):

while True:

self.think(id)

self.pickup_chopsticks(id)

self.eat(id)

self.putdown_chopsticks(id)

def pickup_chopsticks(self, id):

with self.lock:

self.state[id] = State.HUNGRY

self.test(id)

if self.state[id] != State.EATING:

self.condition[id].wait()

def putdown_chopsticks(self, id):

with self.lock:

self.state[id] = State.THINKING

# Check if neighbors can now eat

self.test((id + 4) % 5) # Left neighbor

self.test((id + 1) % 5) # Right neighbor

def test(self, id):

left = (id + 4) % 5

right = (id + 1) % 5

if (self.state[id] == State.HUNGRY and

self.state[left] != State.EATING and

self.state[right] != State.EATING):

self.state[id] = State.EATING

self.condition[id].notify()

def think(self, id):

print(f"Philosopher {id} is thinking")

time.sleep(random.uniform(1, 3))

def eat(self, id):

print(f"Philosopher {id} is eating")

time.sleep(random.uniform(1, 2))

Advanced Solutions and Optimizations

Timeout-Based Solution

This solution prevents indefinite waiting by implementing timeouts:

class TimeoutDiningPhilosophers:

def __init__(self):

self.chopsticks = [threading.Lock() for _ in range(5)]

def philosopher(self, id):

left = id

right = (id + 1) % 5

while True:

self.think(id)

# Try to acquire left chopstick with timeout

if self.chopsticks[left].acquire(timeout=2):

# Try to acquire right chopstick with timeout

if self.chopsticks[right].acquire(timeout=2):

self.eat(id)

self.chopsticks[right].release()

else:

print(f"Philosopher {id} couldn't get right chopstick, backing off")

self.chopsticks[left].release()

else:

print(f"Philosopher {id} couldn't get left chopstick, backing off")

# Random backoff to prevent starvation

time.sleep(random.uniform(0.1, 0.5))

Resource Hierarchy Solution

This approach assigns a global ordering to resources:

class HierarchicalDiningPhilosophers:

def __init__(self):

self.chopsticks = [threading.Lock() for _ in range(5)]

def philosopher(self, id):

left = id

right = (id + 1) % 5

# Always acquire lower-numbered chopstick first

first = min(left, right)

second = max(left, right)

while True:

self.think(id)

self.chopsticks[first].acquire()

self.chopsticks[second].acquire()

self.eat(id)

self.chopsticks[second].release()

self.chopsticks[first].release()

Performance Analysis and Comparison

Real-World Applications

The Dining Philosophers Problem models many real-world scenarios in computer systems:

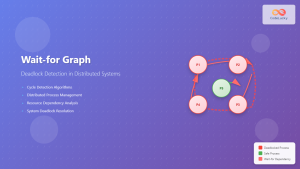

Database Systems

- Lock Management: Transactions acquiring multiple locks on database records

- Deadlock Detection: Implementing timeout-based recovery mechanisms

- Resource Scheduling: Managing concurrent access to database resources

Operating Systems

- Process Synchronization: Managing shared memory and file access

- Device Allocation: Coordinating access to hardware resources

- Network Resources: Managing bandwidth and connection pools

Distributed Systems

- Microservices: Coordinating resource access across services

- Load Balancing: Distributing requests to prevent resource contention

- Cluster Management: Orchestrating resource allocation in distributed environments

Interactive Example

Here’s a complete interactive simulation that demonstrates the problem and solution:

import threading

import time

import random

import queue

from datetime import datetime

class InteractiveDiningPhilosophers:

def __init__(self, solution_type="asymmetric"):

self.chopsticks = [threading.Lock() for _ in range(5)]

self.solution_type = solution_type

self.log_queue = queue.Queue()

self.running = True

if solution_type == "semaphore":

self.eating_semaphore = threading.Semaphore(4)

def log(self, message):

timestamp = datetime.now().strftime("%H:%M:%S.%f")[:-3]

self.log_queue.put(f"[{timestamp}] {message}")

def philosopher(self, id):

left = id

right = (id + 1) % 5

while self.running:

self.think(id)

if self.solution_type == "asymmetric":

self.asymmetric_eat(id, left, right)

elif self.solution_type == "semaphore":

self.semaphore_eat(id, left, right)

elif self.solution_type == "naive":

self.naive_eat(id, left, right)

def asymmetric_eat(self, id, left, right):

if id == 0:

first, second = right, left

else:

first, second = left, right

self.log(f"Philosopher {id} is hungry")

self.chopsticks[first].acquire()

self.log(f"Philosopher {id} picked up chopstick {first}")

self.chopsticks[second].acquire()

self.log(f"Philosopher {id} picked up chopstick {second}")

self.eat(id)

self.chopsticks[second].release()

self.log(f"Philosopher {id} put down chopstick {second}")

self.chopsticks[first].release()

self.log(f"Philosopher {id} put down chopstick {first}")

def think(self, id):

self.log(f"Philosopher {id} is thinking")

time.sleep(random.uniform(0.5, 1.5))

def eat(self, id):

self.log(f"Philosopher {id} is EATING")

time.sleep(random.uniform(0.5, 1.0))

def start_simulation(self, duration=10):

self.log("=== DINING PHILOSOPHERS SIMULATION STARTED ===")

self.log(f"Using solution: {self.solution_type}")

threads = []

for i in range(5):

t = threading.Thread(target=self.philosopher, args=(i,))

threads.append(t)

t.start()

# Run simulation for specified duration

time.sleep(duration)

self.running = False

# Wait for threads to finish

for t in threads:

t.join(timeout=1)

self.log("=== SIMULATION ENDED ===")

# Print collected logs

while not self.log_queue.empty():

print(self.log_queue.get())

# Run the simulation

if __name__ == "__main__":

print("Asymmetric Solution:")

sim = InteractiveDiningPhilosophers("asymmetric")

sim.start_simulation(5)

Key Takeaways and Best Practices

Essential Lessons

- Resource Ordering: Establishing a consistent order for resource acquisition prevents circular wait

- Limiting Concurrency: Sometimes reducing parallelism improves overall system performance

- Timeout Mechanisms: Implementing timeouts provides robustness against indefinite blocking

- Fair Scheduling: Monitor-based solutions can prevent starvation while maintaining efficiency

Design Principles

- Avoid Hold-and-Wait: Acquire all resources at once or none at all

- Break Circular Dependencies: Use asymmetric approaches or resource hierarchies

- Implement Backoff Strategies: Random delays can reduce contention

- Monitor System State: Track resource usage and detect potential deadlocks

Conclusion

The Dining Philosophers Problem remains a cornerstone example in concurrent programming education because it elegantly demonstrates the fundamental challenges of synchronization. From simple asymmetric solutions to sophisticated monitor implementations, each approach offers unique insights into managing shared resources in concurrent systems.

Understanding these concepts is crucial for developing robust, scalable applications in modern computing environments. Whether you’re designing database systems, implementing microservices, or working with multi-threaded applications, the principles learned from the Dining Philosophers Problem will guide you toward creating deadlock-free, efficient concurrent systems.

The key to mastering concurrent programming lies not just in understanding these classical problems, but in recognizing their patterns in real-world scenarios and applying appropriate solutions. As systems continue to grow in complexity and scale, these fundamental synchronization concepts become increasingly valuable for building reliable, high-performance software systems.