What is the Critical Section Problem?

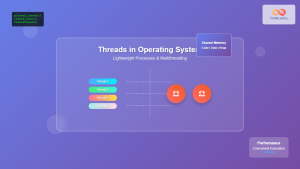

The critical section problem is a fundamental challenge in operating systems where multiple processes need to access shared resources simultaneously. When processes execute concurrently, they may need to access common variables, files, or hardware devices. Without proper coordination, this can lead to race conditions and inconsistent data states.

A critical section is a segment of code where a process accesses shared resources that must not be accessed by more than one process at a time. The critical section problem involves designing protocols to ensure that when one process is executing in its critical section, no other process can execute in its critical section for the same shared resource.

Structure of Critical Section

Every process that needs to access shared resources follows a specific structure:

do {

entry_section(); // Request permission to enter

critical_section(); // Access shared resources

exit_section(); // Release access permission

remainder_section(); // Non-critical code

} while (true);

Components Explained

- Entry Section: Code that requests permission to enter the critical section

- Critical Section: Code segment accessing shared resources

- Exit Section: Code that releases the permission

- Remainder Section: Rest of the process code

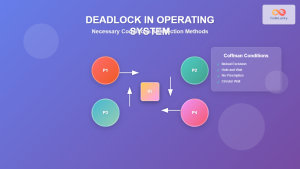

Requirements for Critical Section Solutions

Any solution to the critical section problem must satisfy three essential requirements:

1. Mutual Exclusion

If a process is executing in its critical section, then no other process can execute in its critical section simultaneously.

2. Progress

If no process is executing in the critical section and some processes wish to enter, only those processes not in their remainder section can participate in deciding which will enter next.

3. Bounded Waiting

There must be a bound on the number of times other processes are allowed to enter their critical sections after a process has made a request and before that request is granted.

Classical Solutions to Critical Section Problem

1. Peterson’s Algorithm

Peterson’s algorithm is a software-based solution for two processes. It uses two shared variables:

flag[2]: Boolean array indicating if a process wants to enter critical sectionturn: Integer variable indicating whose turn it is to enter

// Shared variables

boolean flag[2] = {false, false};

int turn = 0;

// Process Pi (i = 0 or 1)

do {

flag[i] = true; // Show interest

turn = j; // Give turn to other process

while (flag[j] && turn == j); // Wait

// Critical Section

flag[i] = false; // Release interest

// Remainder Section

} while (true);

Peterson’s Algorithm Analysis

Advantages:

- Satisfies all three requirements

- Simple software solution

- No special hardware instructions needed

Disadvantages:

- Works only for two processes

- Busy waiting (CPU wastage)

- Not suitable for modern architectures with relaxed memory models

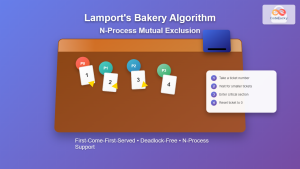

2. Bakery Algorithm

The Bakery Algorithm extends Peterson’s approach to n processes, similar to a bakery numbering system:

// Shared variables

boolean choosing[n] = {false};

int number[n] = {0};

// Process Pi

do {

choosing[i] = true;

number[i] = max(number[0], number[1], ..., number[n-1]) + 1;

choosing[i] = false;

for (j = 0; j < n; j++) {

while (choosing[j]);

while ((number[j] != 0) &&

((number[j], j) < (number[i], i)));

}

// Critical Section

number[i] = 0;

// Remainder Section

} while (true);

3. Hardware-Based Solutions

Test-and-Set Instruction

Many processors provide atomic test-and-set instructions:

boolean test_and_set(boolean *target) {

boolean rv = *target;

*target = true;

return rv;

}

// Shared variable

boolean lock = false;

// Process Pi

do {

while (test_and_set(&lock)); // Acquire lock

// Critical Section

lock = false; // Release lock

// Remainder Section

} while (true);

Compare-and-Swap Instruction

int compare_and_swap(int *value, int expected, int new_value) {

int temp = *value;

if (*value == expected)

*value = new_value;

return temp;

}

// Usage

int lock = 0;

do {

while (compare_and_swap(&lock, 0, 1) != 0); // Acquire

// Critical Section

lock = 0; // Release

// Remainder Section

} while (true);

High-Level Synchronization Primitives

1. Semaphores

Semaphores are integer variables accessed through two atomic operations: wait() and signal().

Binary Semaphore (Mutex)

// Semaphore operations

wait(semaphore S) {

while (S <= 0); // Busy wait

S--;

}

signal(semaphore S) {

S++;

}

// Usage

semaphore mutex = 1;

// Process Pi

do {

wait(mutex);

// Critical Section

signal(mutex);

// Remainder Section

} while (true);

Counting Semaphore Example

// Resource allocation example

semaphore resource_count = 3; // 3 identical resources

// Process requesting resource

do {

wait(resource_count); // Acquire resource

// Use resource (Critical Section)

signal(resource_count); // Release resource

// Other work

} while (true);

2. Mutex Locks

Mutex (Mutual Exclusion) locks are simpler than semaphores, designed specifically for mutual exclusion:

// Mutex structure

typedef struct {

boolean available;

queue waiting_processes;

} mutex_lock;

// Acquire lock

acquire(mutex_lock *lock) {

while (!lock->available); // Spin wait or block

lock->available = false;

}

// Release lock

release(mutex_lock *lock) {

lock->available = true;

}

// Usage

mutex_lock lock;

do {

acquire(&lock);

// Critical Section

release(&lock);

// Remainder Section

} while (true);

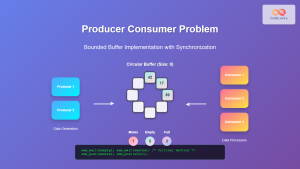

3. Condition Variables

Condition variables allow processes to wait for certain conditions:

// Producer-Consumer with condition variables

mutex_lock mutex;

condition full, empty;

int count = 0;

int buffer[BUFFER_SIZE];

// Producer

void producer() {

while (true) {

// Produce item

lock(mutex);

while (count == BUFFER_SIZE)

wait(full, mutex);

// Add item to buffer

count++;

signal(empty);

unlock(mutex);

}

}

// Consumer

void consumer() {

while (true) {

lock(mutex);

while (count == 0)

wait(empty, mutex);

// Remove item from buffer

count--;

signal(full);

unlock(mutex);

// Consume item

}

}

Real-World Examples and Applications

Database Transaction Management

Database systems use critical sections to ensure ACID properties:

// Bank transfer example

mutex account_mutex;

void transfer(Account from, Account to, double amount) {

acquire(&account_mutex);

// Critical Section

if (from.balance >= amount) {

from.balance -= amount;

to.balance += amount;

log_transaction(from.id, to.id, amount);

}

release(&account_mutex);

}

Web Server Request Handling

// Shared resource: log file

mutex log_mutex;

FILE *log_file;

void handle_request(Request req) {

// Process request

acquire(&log_mutex);

// Critical Section: Write to log

fprintf(log_file, "[%s] %s %s\n",

get_timestamp(), req.method, req.url);

fflush(log_file);

release(&log_mutex);

// Send response

}

Performance Considerations and Trade-offs

Busy Waiting vs Blocking

| Aspect | Busy Waiting | Blocking |

|---|---|---|

| CPU Usage | High (continuous polling) | Low (process sleeps) |

| Response Time | Fast (immediate detection) | Slower (context switch overhead) |

| Best For | Short critical sections | Long critical sections |

| Scalability | Poor with many processes | Better scalability |

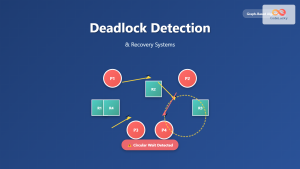

Deadlock Prevention

Critical section solutions must avoid deadlocks:

// Potential deadlock scenario

mutex mutex1, mutex2;

// Process A

void processA() {

acquire(&mutex1);

acquire(&mutex2); // May deadlock with Process B

// Critical work

release(&mutex2);

release(&mutex1);

}

// Process B

void processB() {

acquire(&mutex2);

acquire(&mutex1); // May deadlock with Process A

// Critical work

release(&mutex1);

release(&mutex2);

}

// Solution: Ordered locking

void safe_processA() {

acquire(&mutex1); // Always acquire in same order

acquire(&mutex2);

// Critical work

release(&mutex2);

release(&mutex1);

}

void safe_processB() {

acquire(&mutex1); // Same order as Process A

acquire(&mutex2);

// Critical work

release(&mutex2);

release(&mutex1);

}

Modern Operating System Implementations

Linux Kernel Synchronization

Linux provides several synchronization primitives:

- Spinlocks: For short critical sections in kernel space

- Mutexes: For longer critical sections that can sleep

- Semaphores: For counting resources

- RCU (Read-Copy-Update): For high-performance read-mostly scenarios

// Linux kernel mutex example

#include

static DEFINE_MUTEX(my_mutex);

void critical_function(void) {

mutex_lock(&my_mutex);

// Critical section

// Access shared kernel data

mutex_unlock(&my_mutex);

}

Windows Synchronization Objects

Windows provides various synchronization objects:

// Windows Critical Section

#include

CRITICAL_SECTION cs;

void InitializeSynchronization() {

InitializeCriticalSection(&cs);

}

void SafeFunction() {

EnterCriticalSection(&cs);

// Critical section code

LeaveCriticalSection(&cs);

}

void Cleanup() {

DeleteCriticalSection(&cs);

}

Best Practices and Guidelines

Design Principles

- Keep Critical Sections Short: Minimize time spent in critical sections

- Avoid Nested Locks: Reduce complexity and deadlock risk

- Use Appropriate Synchronization: Choose the right tool for the job

- Consider Lock-Free Algorithms: For high-performance scenarios

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Priority Inversion: Low-priority process holding lock needed by high-priority process

- Lock Convoys: Many processes queuing for the same lock

- Forgot to Release: Always pair acquire with release operations

- Double Locking: Attempting to acquire the same lock twice

Testing and Debugging Synchronization

Race Condition Detection

// Example: Detecting race conditions

#include

#include

int shared_counter = 0;

pthread_mutex_t counter_mutex = PTHREAD_MUTEX_INITIALIZER;

void* increment_thread(void* arg) {

for (int i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

// Uncomment next line to fix race condition

// pthread_mutex_lock(&counter_mutex);

shared_counter++; // Critical section

// pthread_mutex_unlock(&counter_mutex);

}

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t thread1, thread2;

pthread_create(&thread1, NULL, increment_thread, NULL);

pthread_create(&thread2, NULL, increment_thread, NULL);

pthread_join(thread1, NULL);

pthread_join(thread2, NULL);

printf("Final counter value: %d\n", shared_counter);

// Without synchronization: likely < 200000

// With synchronization: exactly 200000

return 0;

}

Debugging Tools

- Valgrind (Helgrind): Detects race conditions in C/C++ programs

- ThreadSanitizer: Google’s race condition detector

- Intel Inspector: Commercial tool for threading error detection

- Static Analysis: Tools like Coverity, PVS-Studio

Conclusion

The critical section problem is fundamental to understanding concurrent programming and operating systems. While simple in concept, implementing robust solutions requires careful consideration of mutual exclusion, progress, and bounded waiting requirements.

Modern operating systems provide sophisticated synchronization primitives that abstract away the complexity of low-level solutions like Peterson’s algorithm. However, understanding these foundational concepts is crucial for:

- Designing efficient concurrent systems

- Debugging synchronization issues

- Making informed decisions about synchronization strategies

- Understanding system behavior under load

As systems become increasingly parallel and distributed, mastering critical section solutions becomes even more important for developers working on high-performance applications, system software, and distributed systems.

- What is the Critical Section Problem?

- Structure of Critical Section

- Requirements for Critical Section Solutions

- Classical Solutions to Critical Section Problem

- High-Level Synchronization Primitives

- Real-World Examples and Applications

- Performance Considerations and Trade-offs

- Modern Operating System Implementations

- Best Practices and Guidelines

- Testing and Debugging Synchronization

- Conclusion