What is Buffering in Operating System?

Buffering in operating systems is a fundamental technique used to temporarily store data in memory while it’s being transferred between two locations with different processing speeds. This mechanism helps bridge the gap between fast processors and slower I/O devices, ensuring smooth data flow and optimal system performance.

When data moves from a fast device (like CPU) to a slower device (like disk storage), or vice versa, buffering provides a temporary holding area that prevents data loss and reduces waiting times. Think of it as a warehouse where goods are temporarily stored before being shipped to their final destination.

Why is Buffering Important?

Buffering serves several critical purposes in modern operating systems:

- Speed Matching: Synchronizes data transfer between devices operating at different speeds

- Data Integrity: Prevents data loss during transmission delays

- System Efficiency: Reduces CPU idle time by allowing concurrent operations

- Resource Optimization: Maximizes utilization of both fast and slow devices

- User Experience: Provides smoother application performance

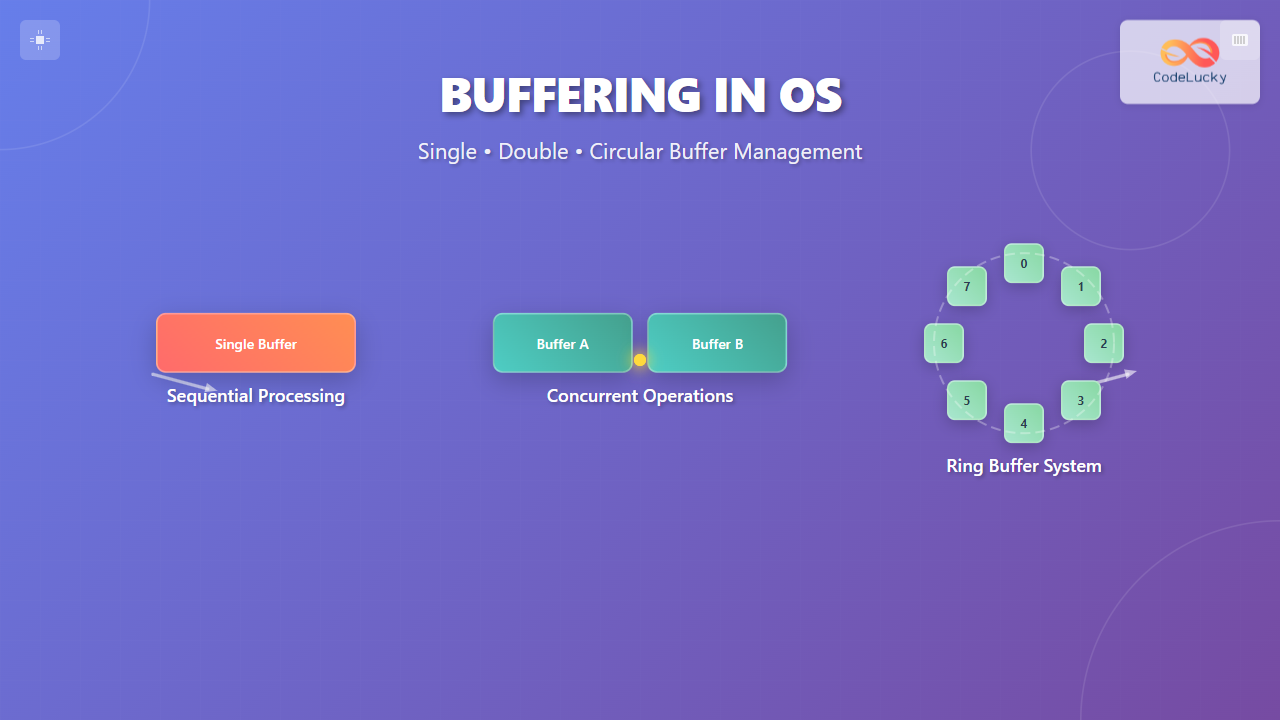

Types of Buffering Techniques

Operating systems implement three primary buffering strategies, each designed for specific scenarios and performance requirements. Let’s explore each type in detail.

Single Buffer System

Single buffering uses one buffer to handle data transfer between two devices. In this system, data is temporarily stored in the buffer before being processed or transmitted to the destination.

How Single Buffer Works

The single buffer operation follows these steps:

- Input device writes data to the buffer

- Processing unit reads data from the buffer

- Processed data is sent to the output device

- Buffer becomes available for the next data chunk

Single Buffer Example

Consider a simple file reading operation:

// Single Buffer Implementation Example

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define BUFFER_SIZE 1024

typedef struct {

char data[BUFFER_SIZE];

int size;

int is_full;

} SingleBuffer;

void read_to_buffer(SingleBuffer* buffer, FILE* file) {

buffer->size = fread(buffer->data, 1, BUFFER_SIZE, file);

buffer->is_full = (buffer->size > 0) ? 1 : 0;

}

void process_buffer(SingleBuffer* buffer) {

if (buffer->is_full) {

printf("Processing %d bytes of data\n", buffer->size);

// Process the data here

buffer->is_full = 0;

}

}

int main() {

SingleBuffer buffer = {0};

FILE* file = fopen("input.txt", "r");

while (!feof(file)) {

read_to_buffer(&buffer, file);

process_buffer(&buffer);

}

fclose(file);

return 0;

}

Advantages of Single Buffer

- Simple implementation and low memory overhead

- Suitable for sequential data processing

- Minimal complexity in buffer management

- Cost-effective for basic applications

Disadvantages of Single Buffer

- Can create bottlenecks when input/output speeds differ significantly

- CPU may remain idle while waiting for I/O operations

- Not optimal for continuous data streams

- Limited concurrent processing capabilities

Double Buffer System

Double buffering employs two buffers working in tandem to achieve better performance. While one buffer receives new data, the other buffer’s data is being processed, enabling concurrent operations.

Double Buffer Operation

The double buffering process works as follows:

- Buffer 1 receives data while Buffer 2 is being processed

- When Buffer 1 is full and Buffer 2 is empty, they swap roles

- This alternating pattern continues throughout the operation

- Both input and processing operations can occur simultaneously

Double Buffer Implementation

// Double Buffer Implementation Example

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#define BUFFER_SIZE 1024

typedef struct {

char data[BUFFER_SIZE];

int size;

int is_ready;

pthread_mutex_t mutex;

} Buffer;

typedef struct {

Buffer buffer1;

Buffer buffer2;

Buffer* active_input;

Buffer* active_output;

} DoubleBuffer;

void* input_thread(void* arg) {

DoubleBuffer* db = (DoubleBuffer*)arg;

FILE* file = fopen("input.txt", "r");

while (!feof(file)) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&db->active_input->mutex);

if (!db->active_input->is_ready) {

db->active_input->size = fread(db->active_input->data, 1, BUFFER_SIZE, file);

db->active_input->is_ready = 1;

// Swap buffers

Buffer* temp = db->active_input;

db->active_input = db->active_output;

db->active_output = temp;

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&db->active_input->mutex);

}

fclose(file);

return NULL;

}

void* output_thread(void* arg) {

DoubleBuffer* db = (DoubleBuffer*)arg;

while (1) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&db->active_output->mutex);

if (db->active_output->is_ready) {

printf("Processing %d bytes\n", db->active_output->size);

// Process the data

db->active_output->is_ready = 0;

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&db->active_output->mutex);

}

return NULL;

}

Advantages of Double Buffer

- Enables concurrent input and output operations

- Reduces CPU idle time significantly

- Better performance for continuous data streams

- Minimizes bottlenecks in data processing pipelines

Disadvantages of Double Buffer

- Higher memory consumption (2x single buffer)

- Increased complexity in implementation

- Requires synchronization mechanisms

- May have overhead in buffer switching

Circular Buffer System

Circular buffering, also known as ring buffering, uses a fixed-size buffer that wraps around when it reaches the end. This creates a continuous loop of buffer space that’s highly efficient for streaming data.

Circular Buffer Structure

Key components of a circular buffer:

- Write Pointer: Points to the next position for writing data

- Read Pointer: Points to the next position for reading data

- Buffer Size: Fixed size that determines buffer capacity

- Full/Empty Flags: Indicate buffer status

Circular Buffer Implementation

// Circular Buffer Implementation Example

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

#define BUFFER_SIZE 8

typedef struct {

int data[BUFFER_SIZE];

int head; // Write pointer

int tail; // Read pointer

int count; // Current number of elements

} CircularBuffer;

void init_circular_buffer(CircularBuffer* cb) {

cb->head = 0;

cb->tail = 0;

cb->count = 0;

}

bool is_full(CircularBuffer* cb) {

return cb->count == BUFFER_SIZE;

}

bool is_empty(CircularBuffer* cb) {

return cb->count == 0;

}

bool write_to_buffer(CircularBuffer* cb, int value) {

if (is_full(cb)) {

printf("Buffer is full! Cannot write %d\n", value);

return false;

}

cb->data[cb->head] = value;

cb->head = (cb->head + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

cb->count++;

printf("Written %d at position %d\n", value,

(cb->head - 1 + BUFFER_SIZE) % BUFFER_SIZE);

return true;

}

bool read_from_buffer(CircularBuffer* cb, int* value) {

if (is_empty(cb)) {

printf("Buffer is empty! Cannot read\n");

return false;

}

*value = cb->data[cb->tail];

cb->tail = (cb->tail + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

cb->count--;

printf("Read %d from position %d\n", *value,

(cb->tail - 1 + BUFFER_SIZE) % BUFFER_SIZE);

return true;

}

void display_buffer(CircularBuffer* cb) {

printf("Buffer status: [");

for (int i = 0; i < BUFFER_SIZE; i++) {

if (i == cb->head && i == cb->tail && cb->count == 0) {

printf(" E "); // Empty position

} else if (i == cb->head) {

printf(" W "); // Write position

} else if (i == cb->tail) {

printf(" R "); // Read position

} else {

printf("%3d", cb->data[i]);

}

}

printf("]\n");

}

int main() {

CircularBuffer cb;

init_circular_buffer(&cb);

// Demonstrate circular buffer operations

printf("=== Circular Buffer Demo ===\n");

// Write some data

for (int i = 1; i <= 5; i++) {

write_to_buffer(&cb, i * 10);

display_buffer(&cb);

}

// Read some data

int value;

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

read_from_buffer(&cb, &value);

display_buffer(&cb);

}

// Write more data (demonstrating wrap-around)

for (int i = 6; i <= 8; i++) {

write_to_buffer(&cb, i * 10);

display_buffer(&cb);

}

return 0;

}

Expected Output

=== Circular Buffer Demo ===

Written 10 at position 0

Buffer status: [ W E E E E E E E ]

Written 20 at position 1

Buffer status: [10 W E E E E E E ]

Written 30 at position 2

Buffer status: [10 20 W E E E E E ]

Written 40 at position 3

Buffer status: [10 20 30 W E E E E ]

Written 50 at position 4

Buffer status: [10 20 30 40 W E E E ]

Read 10 from position 0

Buffer status: [ R 20 30 40 50 E E E ]

Read 20 from position 1

Buffer status: [ E R 30 40 50 E E E ]

Read 30 from position 2

Buffer status: [ E E R 40 50 E E E ]

Written 60 at position 5

Buffer status: [ E E 40 40 50 W E E ]

Written 70 at position 6

Buffer status: [ E E 40 40 50 60 W E ]

Written 80 at position 7

Buffer status: [ E E 40 40 50 60 70 W ]

Real-World Applications of Circular Buffers

Circular buffers are extensively used in various applications:

- Audio Processing: Managing continuous audio streams in media players

- Network Protocols: TCP receive and transmit buffers

- Embedded Systems: UART communication buffers

- Real-time Systems: Sensor data collection and processing

- Graphics: Frame buffers in video processing

Comparison of Buffering Techniques

| Aspect | Single Buffer | Double Buffer | Circular Buffer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory Usage | Low (1x buffer size) | High (2x buffer size) | Fixed (predefined size) |

| Performance | Basic | Good | Excellent for streaming |

| Complexity | Simple | Moderate | Moderate to Complex |

| Concurrency | Limited | Good | Excellent |

| Best Use Case | Simple I/O operations | Batch processing | Continuous data streams |

Buffer Management in Modern Operating Systems

Modern operating systems implement sophisticated buffer management strategies that combine multiple techniques:

Linux Buffer Management

Linux uses several buffer types:

- Page Cache: Caches file system data in memory

- Buffer Cache: Manages block device I/O

- Socket Buffers: Handle network communication

- Pipe Buffers: Manage inter-process communication

Windows Buffer Management

Windows implements:

- System Cache: Unified cache for file system operations

- I/O Manager: Coordinates all I/O operations with buffering

- Memory Manager: Handles virtual memory with buffer pools

Performance Optimization Techniques

To maximize buffer performance, consider these optimization strategies:

Buffer Size Optimization

// Dynamic buffer sizing based on data characteristics

int calculate_optimal_buffer_size(int data_rate, int processing_speed) {

int base_size = 4096; // 4KB base

float ratio = (float)data_rate / processing_speed;

if (ratio > 2.0) {

return base_size * 4; // Large buffer for high data rates

} else if (ratio > 1.0) {

return base_size * 2; // Medium buffer

} else {

return base_size; // Standard buffer

}

}

Buffer Pool Management

Using buffer pools can reduce allocation overhead:

typedef struct BufferPool {

void** buffers;

int* available;

int pool_size;

int buffer_size;

pthread_mutex_t mutex;

} BufferPool;

BufferPool* create_buffer_pool(int pool_size, int buffer_size) {

BufferPool* pool = malloc(sizeof(BufferPool));

pool->buffers = malloc(pool_size * sizeof(void*));

pool->available = malloc(pool_size * sizeof(int));

pool->pool_size = pool_size;

pool->buffer_size = buffer_size;

for (int i = 0; i < pool_size; i++) {

pool->buffers[i] = malloc(buffer_size);

pool->available[i] = 1;

}

pthread_mutex_init(&pool->mutex, NULL);

return pool;

}

Advanced Buffering Concepts

Adaptive Buffering

Modern systems implement adaptive buffering that adjusts buffer parameters based on runtime conditions:

- Dynamic sizing: Buffers grow or shrink based on load

- Priority-based allocation: Critical processes get larger buffers

- Predictive buffering: Pre-allocation based on usage patterns

Multi-level Buffering

Multi-level buffering creates a hierarchy of buffers with different characteristics, optimizing both speed and capacity at each level.

Best Practices for Buffer Implementation

Follow these best practices when implementing buffering systems:

Error Handling

typedef enum {

BUFFER_SUCCESS,

BUFFER_FULL,

BUFFER_EMPTY,

BUFFER_ERROR

} BufferStatus;

BufferStatus safe_write_buffer(CircularBuffer* cb, int value) {

if (cb == NULL) {

return BUFFER_ERROR;

}

if (is_full(cb)) {

return BUFFER_FULL;

}

cb->data[cb->head] = value;

cb->head = (cb->head + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

cb->count++;

return BUFFER_SUCCESS;

}

Thread Safety

Always implement proper synchronization for multi-threaded environments:

- Use mutexes for critical sections

- Implement condition variables for blocking operations

- Consider lock-free implementations for high-performance scenarios

- Use atomic operations where appropriate

Memory Management

- Always free allocated buffer memory

- Use memory pools to reduce fragmentation

- Implement buffer overflow protection

- Consider using memory-mapped files for large buffers

Troubleshooting Common Buffer Issues

Common buffer-related problems and their solutions:

Buffer Overflow

Problem: Writing beyond buffer boundaries

Solution: Always check buffer capacity before writing

bool safe_buffer_write(Buffer* buf, const void* data, size_t size) {

if (buf->used + size > buf->capacity) {

return false; // Would overflow

}

memcpy(buf->data + buf->used, data, size);

buf->used += size;

return true;

}

Buffer Underflow

Problem: Reading from empty buffer

Solution: Check buffer contents before reading

Deadlock Prevention

Problem: Multiple threads waiting for buffer resources

Solution: Implement timeout mechanisms and proper lock ordering

Future of Buffering Technology

Emerging trends in buffer management include:

- AI-driven buffer optimization: Machine learning algorithms predict optimal buffer configurations

- Non-volatile memory integration: Using persistent memory technologies for buffers

- Heterogeneous memory systems: Combining different memory types for optimal performance

- Cloud-native buffering: Distributed buffer systems across multiple nodes

Conclusion

Buffering is a cornerstone technology in operating systems that enables efficient data management between components with varying processing speeds. Understanding the differences between single, double, and circular buffers helps developers choose the right approach for their specific use cases.

Single buffers work well for simple, sequential operations with minimal memory overhead. Double buffers excel in scenarios requiring concurrent input and output operations, while circular buffers are ideal for continuous data streams and real-time applications.

Modern operating systems combine these techniques with advanced features like adaptive sizing, multi-level hierarchies, and intelligent caching to deliver optimal performance. As technology continues to evolve, buffering mechanisms will adapt to leverage new hardware capabilities and meet the demands of increasingly complex applications.

Whether you’re developing system software, embedded applications, or high-performance computing solutions, mastering buffering concepts will significantly improve your ability to create efficient and robust systems.