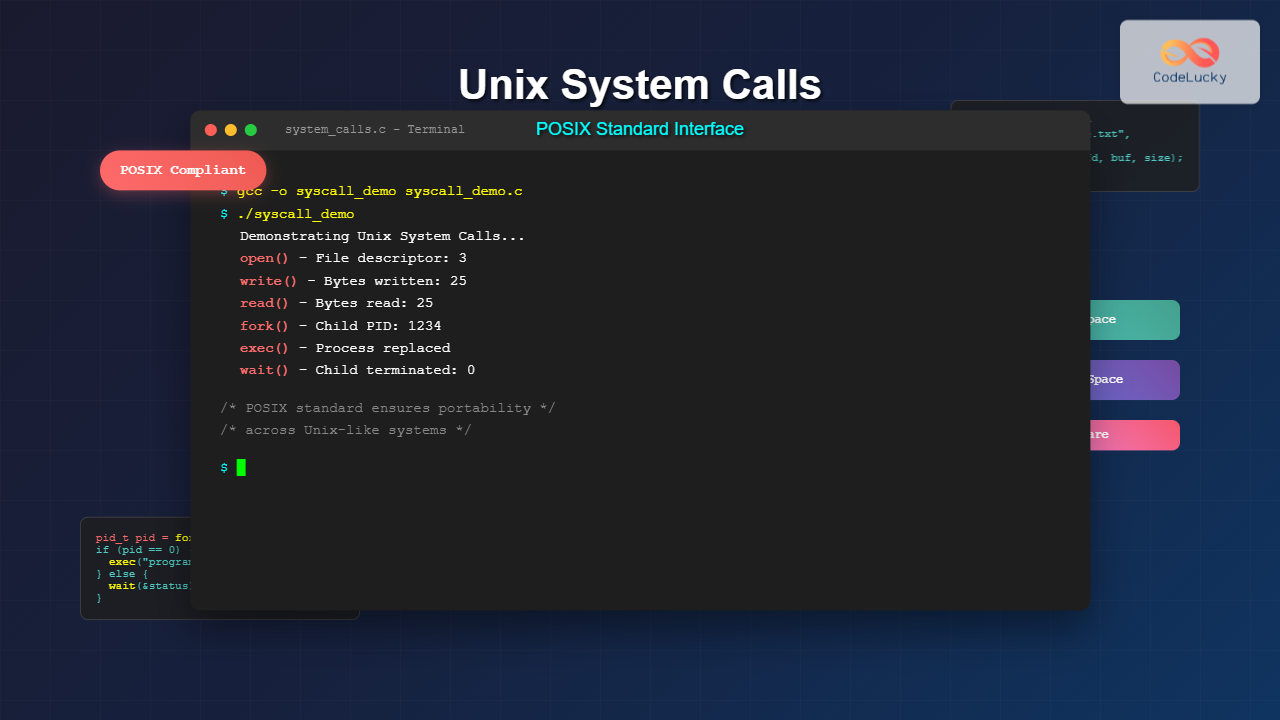

Unix system calls form the fundamental bridge between user applications and the operating system kernel. These low-level interfaces provide direct access to system resources, enabling programs to perform essential operations like file manipulation, process management, and network communication.

The POSIX (Portable Operating System Interface) standard ensures consistency across Unix-like systems, making your code portable between different platforms including Linux, macOS, and various Unix distributions.

Understanding System Calls Architecture

System calls operate at the boundary between user space and kernel space. When your program needs to interact with hardware or system resources, it cannot do so directly due to security and stability reasons. Instead, it must request the kernel to perform these operations through system calls.

System Call Mechanism

The system call process involves several steps:

- Trap instruction: Application executes a special CPU instruction

- Mode switch: CPU switches from user mode to kernel mode

- Kernel execution: Operating system performs the requested operation

- Return: Control returns to user space with results

Essential File System Operations

File operations represent the most commonly used system calls in Unix programming. These calls provide direct access to the file system through file descriptors.

Opening and Creating Files

The open() system call creates or opens a file and returns a file descriptor:

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// Open existing file for reading

int fd1 = open("example.txt", O_RDONLY);

if (fd1 == -1) {

perror("Error opening file");

return 1;

}

// Create new file with write permissions

int fd2 = open("newfile.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0644);

if (fd2 == -1) {

perror("Error creating file");

close(fd1);

return 1;

}

printf("Files opened successfully\n");

printf("File descriptor 1: %d\n", fd1);

printf("File descriptor 2: %d\n", fd2);

close(fd1);

close(fd2);

return 0;

}Output:

Files opened successfully

File descriptor 1: 3

File descriptor 2: 4Reading and Writing Data

The read() and write() system calls handle data transfer:

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

char buffer[100];

char message[] = "Hello, Unix System Calls!";

// Write to file

int fd = open("demo.txt", O_CREAT | O_RDWR | O_TRUNC, 0644);

ssize_t bytes_written = write(fd, message, strlen(message));

printf("Bytes written: %zd\n", bytes_written);

// Reset file pointer to beginning

lseek(fd, 0, SEEK_SET);

// Read from file

ssize_t bytes_read = read(fd, buffer, sizeof(buffer) - 1);

buffer[bytes_read] = '\0'; // Null terminate

printf("Bytes read: %zd\n", bytes_read);

printf("Content: %s\n", buffer);

close(fd);

return 0;

}Output:

Bytes written: 25

Bytes read: 25

Content: Hello, Unix System Calls!Process Management System Calls

Process management forms the core of multitasking operating systems. Unix provides powerful system calls for creating, managing, and synchronizing processes.

Process Creation with fork()

The fork() system call creates a new process by duplicating the calling process:

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

pid_t pid = fork();

if (pid == -1) {

perror("fork failed");

exit(1);

} else if (pid == 0) {

// Child process

printf("Child process: PID = %d, Parent PID = %d\n",

getpid(), getppid());

// Child does some work

for (int i = 1; i <= 3; i++) {

printf("Child working... step %d\n", i);

sleep(1);

}

printf("Child process terminating\n");

exit(42); // Exit with status 42

} else {

// Parent process

printf("Parent process: PID = %d, Child PID = %d\n",

getpid(), pid);

// Wait for child to complete

int status;

pid_t waited_pid = wait(&status);

printf("Parent: Child %d terminated with status %d\n",

waited_pid, WEXITSTATUS(status));

}

return 0;

}Output:

Parent process: PID = 1234, Child PID = 1235

Child process: PID = 1235, Parent PID = 1234

Child working... step 1

Child working... step 2

Child working... step 3

Child process terminating

Parent: Child 1235 terminated with status 42Program Execution with exec() Family

The exec() family replaces the current process image with a new program:

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

pid_t pid = fork();

if (pid == -1) {

perror("fork failed");

exit(1);

} else if (pid == 0) {

// Child process - execute 'ls' command

printf("Child: About to execute 'ls -l'\n");

// Replace process image with 'ls' program

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", "-l", ".", NULL);

// This line should never execute if exec() succeeds

perror("exec failed");

exit(1);

} else {

// Parent process

printf("Parent: Waiting for child to complete ls command\n");

int status;

wait(&status);

printf("Parent: Child completed with status %d\n",

WEXITSTATUS(status));

}

return 0;

}Signal Handling and Inter-Process Communication

Signals provide a mechanism for asynchronous communication between processes and handling system events.

Signal Registration and Handling

#include <signal.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

volatile sig_atomic_t signal_received = 0;

void signal_handler(int sig) {

switch(sig) {

case SIGUSR1:

printf("Received SIGUSR1 signal\n");

signal_received = 1;

break;

case SIGINT:

printf("Received SIGINT (Ctrl+C)\n");

printf("Gracefully shutting down...\n");

exit(0);

break;

}

}

int main() {

// Register signal handlers

signal(SIGUSR1, signal_handler);

signal(SIGINT, signal_handler);

printf("Process PID: %d\n", getpid());

printf("Waiting for signals... (Press Ctrl+C to exit)\n");

printf("Send SIGUSR1 with: kill -USR1 %d\n", getpid());

// Main program loop

while (1) {

if (signal_received) {

printf("Processing signal...\n");

signal_received = 0;

}

printf("Working...\n");

sleep(2);

}

return 0;

}Memory Management System Calls

Unix provides system calls for dynamic memory allocation and memory-mapped file operations.

Memory Mapping with mmap()

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main() {

const char* filename = "mmap_example.txt";

const char* content = "Memory mapped file content example";

// Create and write initial content

int fd = open(filename, O_CREAT | O_RDWR | O_TRUNC, 0644);

write(fd, content, strlen(content));

// Get file size

struct stat sb;

fstat(fd, &sb);

// Memory map the file

char* mapped = mmap(NULL, sb.st_size, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE,

MAP_SHARED, fd, 0);

if (mapped == MAP_FAILED) {

perror("mmap failed");

close(fd);

return 1;

}

printf("Original content: %.*s\n", (int)sb.st_size, mapped);

// Modify through memory mapping

if (sb.st_size >= 6) {

memcpy(mapped, "MAPPED", 6);

}

// Synchronize changes

msync(mapped, sb.st_size, MS_SYNC);

printf("Modified content: %.*s\n", (int)sb.st_size, mapped);

// Cleanup

munmap(mapped, sb.st_size);

close(fd);

return 0;

}Output:

Original content: Memory mapped file content example

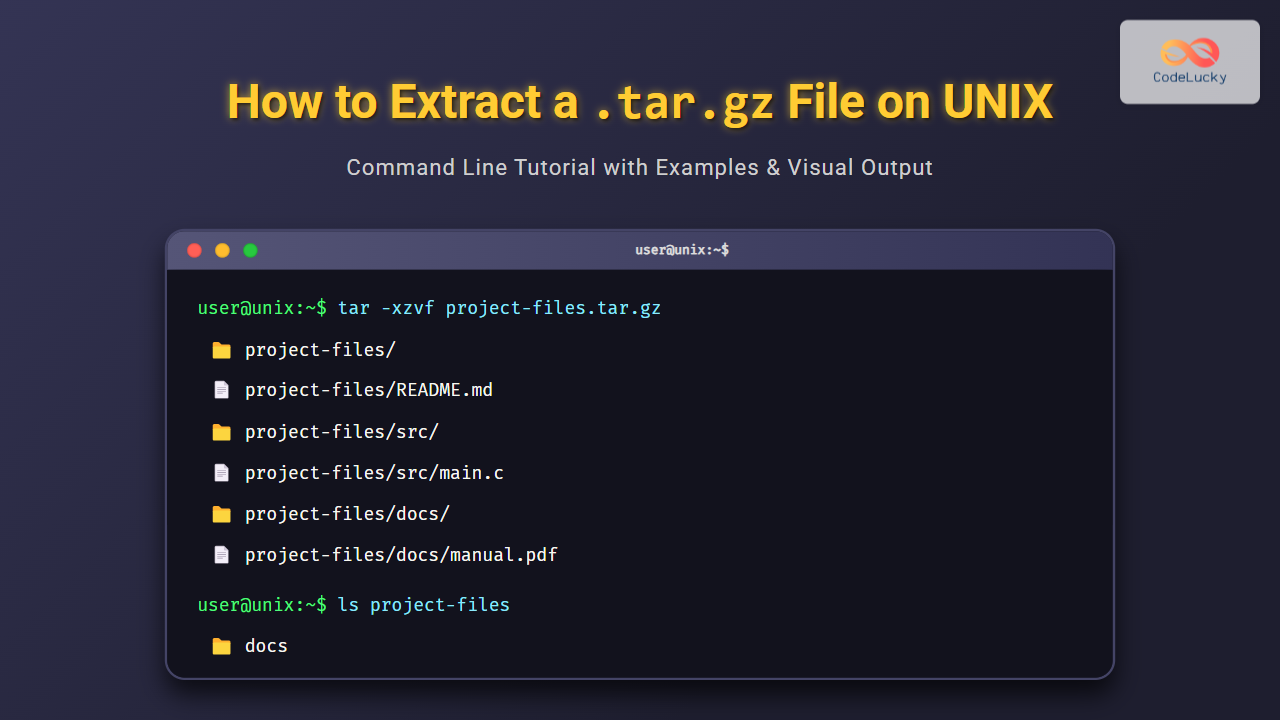

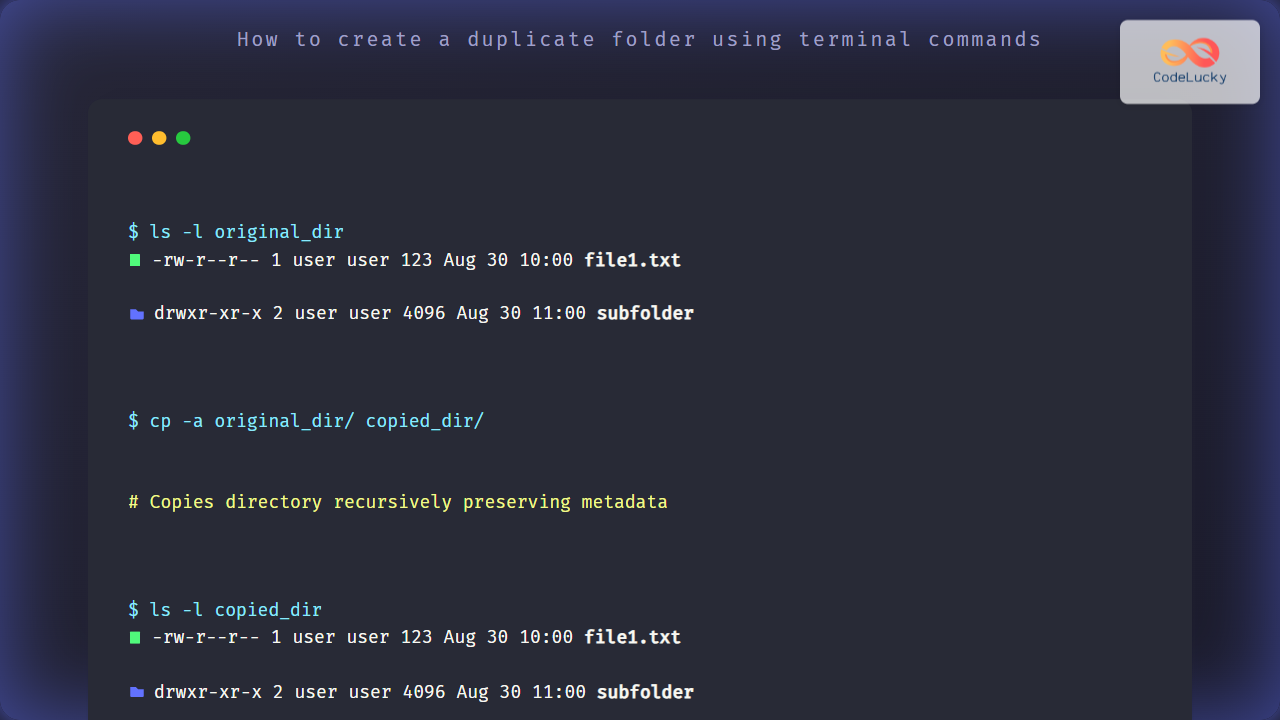

Modified content: MAPPED mapped file content exampleDirectory Operations and File System Navigation

Directory operations enable programs to traverse and manipulate the file system structure.

Directory Traversal Example

#include <dirent.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void list_directory(const char* path) {

DIR* dir = opendir(path);

if (dir == NULL) {

perror("opendir failed");

return;

}

printf("Contents of directory '%s':\n", path);

printf("%-20s %-10s %s\n", "Name", "Type", "Size");

printf("%-20s %-10s %s\n", "----", "----", "----");

struct dirent* entry;

struct stat file_stat;

char full_path[1024];

while ((entry = readdir(dir)) != NULL) {

// Skip . and .. entries

if (strcmp(entry->d_name, ".") == 0 ||

strcmp(entry->d_name, "..") == 0) {

continue;

}

// Create full path

snprintf(full_path, sizeof(full_path), "%s/%s", path, entry->d_name);

// Get file statistics

if (stat(full_path, &file_stat) == 0) {

const char* type = S_ISDIR(file_stat.st_mode) ? "Directory" :

S_ISREG(file_stat.st_mode) ? "File" : "Other";

printf("%-20s %-10s %ld bytes\n",

entry->d_name, type, file_stat.st_size);

}

}

closedir(dir);

}

int main() {

// Create a test directory structure

mkdir("test_dir", 0755);

mkdir("test_dir/subdir", 0755);

// Create some test files

FILE* fp = fopen("test_dir/file1.txt", "w");

fprintf(fp, "Test content 1");

fclose(fp);

fp = fopen("test_dir/file2.txt", "w");

fprintf(fp, "Test content 2 with more data");

fclose(fp);

// List directory contents

list_directory("test_dir");

return 0;

}Output:

Contents of directory 'test_dir':

Name Type Size

---- ---- ----

file1.txt File 14 bytes

file2.txt File 30 bytes

subdir Directory 4096 bytesError Handling and System Call Best Practices

Proper error handling is crucial for robust system programming. Unix system calls use consistent error reporting mechanisms.

Comprehensive Error Handling Pattern

#include <errno.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int safe_file_operation(const char* filename) {

int fd = -1;

char buffer[256];

ssize_t bytes_read;

// Attempt to open file

fd = open(filename, O_RDONLY);

if (fd == -1) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error opening '%s': %s (errno: %d)\n",

filename, strerror(errno), errno);

return -1;

}

printf("Successfully opened '%s' with fd: %d\n", filename, fd);

// Attempt to read data

bytes_read = read(fd, buffer, sizeof(buffer) - 1);

if (bytes_read == -1) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error reading from '%s': %s\n",

filename, strerror(errno));

close(fd); // Cleanup on error

return -1;

}

if (bytes_read == 0) {

printf("End of file reached\n");

} else {

buffer[bytes_read] = '\0';

printf("Read %zd bytes: %.50s%s\n",

bytes_read, buffer, bytes_read > 50 ? "..." : "");

}

// Always close file descriptor

if (close(fd) == -1) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error closing file: %s\n", strerror(errno));

return -1;

}

return 0;

}

int main() {

// Test with existing file

printf("=== Testing with existing file ===\n");

safe_file_operation("/etc/hostname");

// Test with non-existent file

printf("\n=== Testing with non-existent file ===\n");

safe_file_operation("nonexistent.txt");

return 0;

}Advanced System Call Concepts

File Descriptor Management

Understanding file descriptor limits and proper resource management:

#include <sys/resource.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

void display_fd_limits() {

struct rlimit rl;

// Get file descriptor limits

if (getrlimit(RLIMIT_NOFILE, &rl) == 0) {

printf("File Descriptor Limits:\n");

printf(" Soft limit: %ld\n", rl.rlim_cur);

printf(" Hard limit: %ld\n", rl.rlim_max);

}

// Display current file descriptors

printf("\nStandard file descriptors:\n");

printf(" STDIN_FILENO: %d\n", STDIN_FILENO);

printf(" STDOUT_FILENO: %d\n", STDOUT_FILENO);

printf(" STDERR_FILENO: %d\n", STDERR_FILENO);

}

int main() {

display_fd_limits();

// Demonstrate file descriptor allocation

printf("\nOpening multiple files:\n");

int fds[5];

char filename[20];

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

snprintf(filename, sizeof(filename), "temp%d.txt", i);

fds[i] = open(filename, O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0644);

if (fds[i] != -1) {

printf(" %s -> fd: %d\n", filename, fds[i]);

}

}

// Clean up

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

if (fds[i] != -1) {

close(fds[i]);

snprintf(filename, sizeof(filename), "temp%d.txt", i);

unlink(filename); // Remove file

}

}

return 0;

}Performance Considerations and Optimization

System calls involve context switching overhead. Understanding performance implications helps optimize applications:

- Minimize system calls: Use buffered I/O when possible

- Batch operations: Read/write larger chunks of data

- Use appropriate flags: Choose optimal file access modes

- Resource cleanup: Always close file descriptors and free resources

Performance Comparison Example

#include <time.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

double time_operation(void (*operation)(), const char* description) {

clock_t start = clock();

operation();

clock_t end = clock();

double time_spent = ((double)(end - start)) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC;

printf("%s: %.6f seconds\n", description, time_spent);

return time_spent;

}

void byte_by_byte_write() {

int fd = open("test_small.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0644);

char data = 'A';

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

write(fd, &data, 1);

}

close(fd);

unlink("test_small.txt");

}

void bulk_write() {

int fd = open("test_bulk.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0644);

char data[10000];

memset(data, 'A', sizeof(data));

write(fd, data, sizeof(data));

close(fd);

unlink("test_bulk.txt");

}

int main() {

printf("Performance comparison:\n");

time_operation(byte_by_byte_write, "Byte-by-byte write (10,000 syscalls)");

time_operation(bulk_write, "Bulk write (1 syscall)");

return 0;

}Conclusion

Unix system calls and the POSIX standard provide a powerful, standardized interface for system programming. Mastering these concepts enables you to:

- Build efficient system-level applications

- Write portable code across Unix-like systems

- Implement proper error handling and resource management

- Understand the fundamental operations of modern operating systems

By following POSIX standards and implementing proper error handling, your applications will be robust, portable, and maintainable across different Unix environments. Remember to always clean up resources, handle errors appropriately, and consider performance implications when designing system-level software.

The examples provided in this guide demonstrate practical usage patterns that you can adapt for your specific requirements. Whether building system utilities, servers, or embedded applications, these fundamental system call patterns form the foundation of effective Unix programming.

- Understanding System Calls Architecture

- Essential File System Operations

- Process Management System Calls

- Signal Handling and Inter-Process Communication

- Memory Management System Calls

- Directory Operations and File System Navigation

- Error Handling and System Call Best Practices

- Advanced System Call Concepts

- Performance Considerations and Optimization

- Conclusion