In the realm of operating system security, the Trusted Computing Base (TCB) represents the foundation upon which all system security depends. As cyber threats continue to evolve, understanding how to design and implement secure kernels becomes crucial for system architects and security professionals. This comprehensive guide explores the fundamental concepts, architectural patterns, and implementation strategies that make modern operating systems resilient against sophisticated attacks.

Understanding the Trusted Computing Base

The Trusted Computing Base encompasses all hardware, software, and firmware components that are critical to a system’s security policy enforcement. Think of it as the security foundation that must remain uncompromised for the entire system to maintain its security properties.

The TCB consists of several key components:

- Security Kernel: The core component that enforces security policies

- Hardware Security Modules: Specialized hardware for cryptographic operations

- Reference Monitor: The abstract machine that mediates all access attempts

- Security Policy Database: Rules governing access control decisions

Security Kernel Design Principles

A well-designed security kernel follows several fundamental principles that ensure robust protection against various attack vectors.

Complete Mediation

Every access attempt to system resources must pass through the security kernel. This principle ensures that no unauthorized access can bypass security controls. The kernel acts as a mandatory checkpoint for all resource requests.

// Example: File access mediation

int secure_file_open(const char* filename, int mode, uid_t user_id) {

// Step 1: Validate user permissions

if (!check_user_permissions(user_id, filename, mode)) {

audit_log(SECURITY_VIOLATION, user_id, filename);

return -EACCES;

}

// Step 2: Apply security policy

if (!apply_security_policy(filename, mode)) {

return -EPERM;

}

// Step 3: Proceed with actual file operation

return system_open(filename, mode);

}

Least Privilege

The security kernel operates with the minimum privileges necessary to perform its functions. This reduces the attack surface and limits potential damage from compromised components.

Economy of Mechanism

Security mechanisms should be as simple as possible to minimize the likelihood of implementation errors. Complex systems are harder to verify and more prone to vulnerabilities.

Reference Monitor Implementation

The reference monitor is the heart of the security kernel, responsible for enforcing access control policies. It must satisfy three critical properties:

Tamper-Proof

The reference monitor itself must be protected from modification by untrusted processes. This is typically achieved through hardware memory protection and privilege separation.

// Protected reference monitor structure

typedef struct {

access_matrix_t *policy_matrix; // Protected in kernel space

audit_log_t *security_log; // Write-only for user processes

crypto_keys_t *verification_keys; // Hardware-protected

} reference_monitor_t;

// Function to validate monitor integrity

bool verify_monitor_integrity(reference_monitor_t *monitor) {

return crypto_verify_signature(monitor, system_key) &&

check_memory_protection(monitor) &&

validate_policy_consistency(monitor->policy_matrix);

}

Always Invoked

Every access attempt must be mediated by the reference monitor without exception. This requires careful system design to ensure complete coverage.

Small Enough to Verify

The reference monitor should be simple enough to undergo thorough security analysis and formal verification.

Multi-Level Security Architecture

Modern security kernels often implement multi-level security (MLS) models that support different classification levels and compartments. This approach is essential for environments requiring strict information flow control.

Bell-LaPadula Model Implementation

The Bell-LaPadula model prevents unauthorized disclosure of information through two key properties:

- No Read Up: Subjects cannot read objects at higher security levels

- No Write Down: Subjects cannot write to objects at lower security levels

class SecurityLevel:

def __init__(self, level, compartments):

self.level = level # 0=Unclassified, 1=Confidential, 2=Secret, 3=TopSecret

self.compartments = set(compartments)

def dominates(self, other):

"""Check if this security level dominates another"""

return (self.level >= other.level and

self.compartments >= other.compartments)

def check_read_access(subject_level, object_level):

"""Implement 'no read up' policy"""

return subject_level.dominates(object_level)

def check_write_access(subject_level, object_level):

"""Implement 'no write down' policy"""

return object_level.dominates(subject_level)

# Example usage

user_clearance = SecurityLevel(2, {'CRYPTO', 'INTEL'}) # Secret level

document_class = SecurityLevel(1, {'CRYPTO'}) # Confidential level

can_read = check_read_access(user_clearance, document_class) # True

can_write = check_write_access(user_clearance, document_class) # False

Capability-Based Security

An alternative approach to traditional access control lists (ACLs) is capability-based security, where access rights are represented as unforgeable tokens that can be passed between processes.

// Capability structure

typedef struct capability {

object_id_t object; // Target resource identifier

rights_mask_t permissions; // Allowed operations (read, write, execute)

crypto_hash_t integrity_hash; // Prevents tampering

timestamp_t expiration; // Optional time-based restrictions

} capability_t;

// Capability verification function

bool verify_capability(capability_t *cap, operation_t op) {

// Check integrity

if (!verify_hash(cap)) {

return false;

}

// Check expiration

if (cap->expiration && current_time() > cap->expiration) {

revoke_capability(cap);

return false;

}

// Check permissions

return (cap->permissions & op) != 0;

}

Secure Boot and Chain of Trust

A robust TCB begins its security guarantees from the moment the system powers on. Secure boot ensures that only verified, trusted code executes during the boot process.

// Secure boot verification process

typedef struct boot_signature {

uint8_t signature[256]; // RSA-2048 signature

uint8_t hash[32]; // SHA-256 hash of code

uint32_t code_size; // Size of signed code

} boot_signature_t;

bool verify_boot_component(void *code, size_t size, boot_signature_t *sig) {

uint8_t computed_hash[32];

// Compute hash of loaded code

sha256(code, size, computed_hash);

// Verify hash matches signature

if (memcmp(computed_hash, sig->hash, 32) != 0) {

return false;

}

// Verify RSA signature using hardware root key

return rsa_verify(sig->signature, sig->hash, hardware_public_key);

}

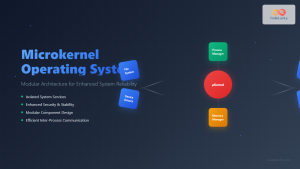

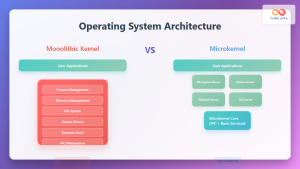

Microkernel vs Monolithic Kernel Security

The choice between microkernel and monolithic kernel architectures significantly impacts the size and complexity of the TCB.

Microkernel Advantages

- Smaller TCB: Only essential services run in kernel mode

- Fault Isolation: Driver failures don’t crash the entire system

- Easier Verification: Smaller codebase simplifies security analysis

Implementation Example

// Microkernel message passing for secure IPC

typedef struct message {

process_id_t sender;

process_id_t receiver;

uint32_t message_type;

size_t data_length;

capability_t required_caps[MAX_CAPS];

uint8_t data[];

} secure_message_t;

int send_secure_message(secure_message_t *msg) {

// Verify sender capabilities

if (!verify_sender_capabilities(msg->sender, msg->required_caps)) {

return -EPERM;

}

// Validate message integrity

if (!validate_message_format(msg)) {

return -EINVAL;

}

// Deliver message through secure channel

return deliver_message(msg);

}

Real-World TCB Implementations

Several operating systems have successfully implemented robust TCBs using different approaches:

seL4 Microkernel

seL4 represents the gold standard for formally verified security kernels. Its TCB consists of only about 10,000 lines of C code, making comprehensive verification feasible.

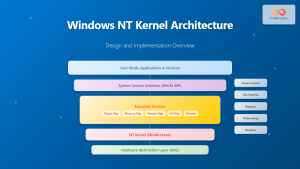

Windows Security Architecture

Modern Windows implements a virtualization-based security (VBS) architecture that uses hypervisor technology to protect critical system components.

Linux Security Modules

Linux uses a pluggable framework allowing different security models (SELinux, AppArmor, Smack) to be integrated into the kernel.

Performance Considerations

Security kernels must balance robust protection with system performance. Key optimization strategies include:

- Hardware Acceleration: Using dedicated security processors

- Caching: Storing frequently accessed security decisions

- Lazy Evaluation: Deferring expensive checks when possible

// Performance-optimized access control cache

typedef struct acl_cache_entry {

subject_id_t subject;

object_id_t object;

operation_t operation;

decision_t cached_decision;

timestamp_t cache_time;

uint32_t hit_count;

} acl_cache_entry_t;

decision_t fast_access_check(subject_id_t subject, object_id_t object, operation_t op) {

// Check cache first

acl_cache_entry_t *entry = lookup_cache(subject, object, op);

if (entry && (current_time() - entry->cache_time) < CACHE_TTL) {

entry->hit_count++;

return entry->cached_decision;

}

// Perform full security check

decision_t decision = full_security_check(subject, object, op);

// Update cache

update_cache(subject, object, op, decision);

return decision;

}

Future Trends and Challenges

The evolution of computing architectures presents new challenges and opportunities for TCB design:

- Cloud Computing: Extending trust boundaries across distributed systems

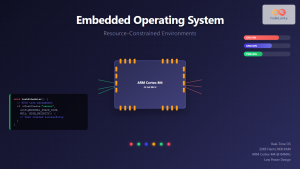

- IoT Devices: Implementing TCB in resource-constrained environments

- Quantum Computing: Preparing for post-quantum cryptographic requirements

- AI/ML Integration: Securing machine learning workloads within the TCB

Best Practices for TCB Implementation

When designing and implementing a trusted computing base, follow these proven practices:

- Minimize Attack Surface: Keep the TCB as small as possible

- Defense in Depth: Implement multiple layers of security controls

- Continuous Monitoring: Implement comprehensive audit and logging systems

- Regular Updates: Maintain currency with security patches and updates

- Formal Verification: Use mathematical proofs where feasible

Conclusion

The Trusted Computing Base and security kernel design represent critical foundations for modern system security. As threats continue to evolve, the principles and practices outlined in this guide provide a roadmap for building resilient, secure operating systems. Whether implementing a microkernel architecture, integrating capability-based security, or designing multi-level security systems, success depends on careful attention to the fundamental principles of complete mediation, least privilege, and economy of mechanism.

The future of computing security will require even more sophisticated approaches to TCB design, incorporating emerging technologies while maintaining the core security properties that make systems trustworthy. By understanding these concepts and applying them thoughtfully, system architects can build the secure foundations that our increasingly connected world demands.