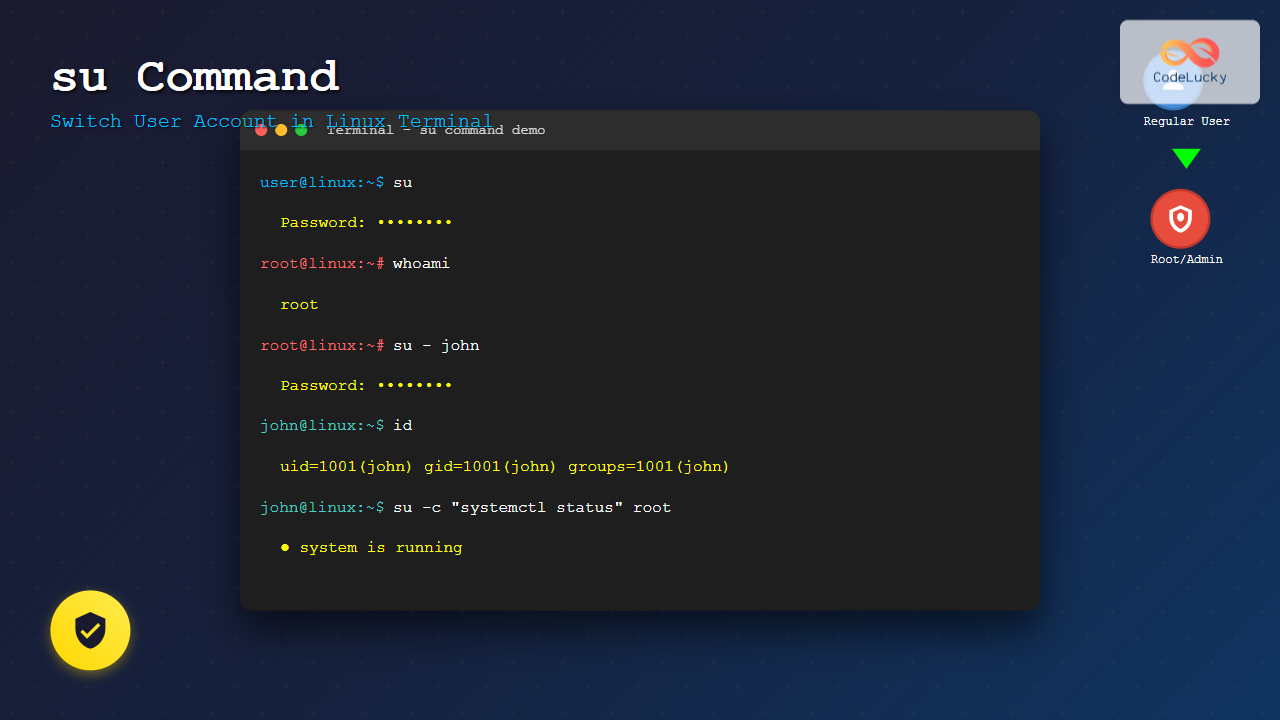

The su command (substitute user or switch user) is one of the most fundamental commands in Linux system administration. It allows you to switch from your current user account to another user account without logging out of your current session. This powerful command is essential for system administrators, developers, and power users who need to perform tasks with different privilege levels.

What is the su Command?

The su command enables users to assume the identity of another user account, most commonly the root (superuser) account. When you execute the su command, it starts a new shell session under the specified user’s credentials, inheriting their permissions, environment variables, and access rights.

Unlike sudo, which executes individual commands with elevated privileges, su creates an entirely new shell session as the target user. This makes it particularly useful for performing multiple administrative tasks without repeatedly entering passwords.

Basic Syntax and Usage

The basic syntax of the su command follows this pattern:

su [options] [username]If no username is specified, the command defaults to switching to the root user. Here are some fundamental usage examples:

Switching to Root User

$ su

Password:

# When you run su without any arguments, the system prompts for the root password. After successful authentication, your shell prompt typically changes from $ to #, indicating you now have root privileges.

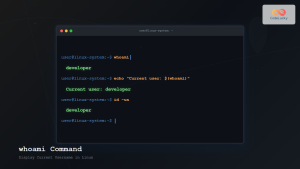

Switching to a Specific User

$ su john

Password:

$ whoami

johnThis command switches to the user account “john”. You’ll need to enter john’s password to complete the switch.

Common su Command Options

The su command offers several options to modify its behavior:

The Login Shell Option (-l or -)

$ su - john

Password:

$ pwd

/home/johnUsing su - or su -l creates a login shell, which:

- Loads the target user’s complete environment

- Changes to the user’s home directory

- Executes the user’s login scripts (.bashrc, .profile, etc.)

- Sets environment variables as if the user logged in directly

Preserving Environment (-m or -p)

$ export CUSTOM_VAR="myvalue"

$ su -m john

Password:

$ echo $CUSTOM_VAR

myvalueThe -m or -p option preserves your current environment variables when switching users, which can be useful for maintaining specific configurations.

Executing Commands (-c)

$ su -c "ls -la /root" root

Password:

total 32

drwx------ 5 root root 4096 Aug 25 10:30 .

drwxr-xr-x 23 root root 4096 Aug 20 14:15 ..The -c option allows you to execute a single command as another user without starting an interactive shell session.

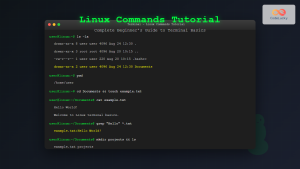

Practical Examples and Use Cases

System Administration Tasks

System administrators frequently use su to perform maintenance tasks:

$ su -

Password:

# systemctl restart apache2

# tail -f /var/log/apache2/error.log

# exit

logout

$ This example shows switching to root, restarting the Apache web server, monitoring logs, and then returning to the original user account.

File Operations with Different Permissions

$ ls -la /etc/shadow

-rw-r----- 1 root shadow 1234 Aug 25 10:15 /etc/shadow

$ cat /etc/shadow

cat: /etc/shadow: Permission denied

$ su -c "head -3 /etc/shadow"

Password:

root:$6$randomhash...:18500:0:99999:7:::

daemon:*:18375:0:99999:7:::

bin:*:18375:0:99999:7:::This demonstrates accessing files that require elevated privileges using the su command.

Development Environment Setup

$ su developer -c "cd /var/www && git pull origin main"

Password:

Already up to date.

$ su developer -l

Password:

developer@server:~$ npm install

developer@server:~$ npm run build

developer@server:~$ exit

logout

$ Developers often use su to switch to deployment users for application updates and builds.

Security Considerations and Best Practices

Password Security

When using su, you must know the target user’s password. This creates several security implications:

- Password sharing: Multiple users knowing root passwords can be a security risk

- Audit trail: su doesn’t log individual commands executed after switching

- Session management: Long-running root sessions increase security exposure

Limiting Root Access

Many systems restrict direct root access for security. Check your system’s configuration:

$ grep "^root:" /etc/passwd

root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash

$ su -c "passwd -S root"

Password:

root P 08/25/2025 0 99999 7 -1Using sudo vs su

Consider these factors when choosing between su and sudo:

| Feature | su | sudo |

|---|---|---|

| Password Required | Target user’s password | Current user’s password |

| Session Type | New shell session | Single command execution |

| Logging | Login/logout events | Individual commands logged |

| Granular Control | Full user access | Specific commands/permissions |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Authentication Failures

$ su john

Password:

su: Authentication failure

$ Common causes and solutions:

- Incorrect password: Verify the password is correct

- Account locked: Check if the account is disabled

- Shell restrictions: Ensure the user has a valid shell assigned

Environment Issues

$ su john

Password:

$ echo $HOME

/home/originaluser

$ echo $PATH

/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/binIf environment variables aren’t set correctly, use the login option:

$ su - john

Password:

$ echo $HOME

/home/johnPermission Problems

$ su -c "mkdir /root/testdir"

Password:

mkdir: cannot create directory '/root/testdir': Permission deniedEnsure you’re switching to a user with appropriate permissions for the task.

Advanced su Command Features

Shell Specification

$ su -s /bin/zsh john

Password:

john@server% echo $SHELL

/bin/zshThe -s option allows you to specify which shell to use for the session.

Group Switching

$ su -g wheel john

Password:

$ id

uid=1001(john) gid=10(wheel) groups=10(wheel),1001(john)Use -g to specify the primary group for the session.

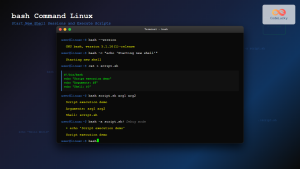

Scripting with su

While su can be used in scripts, it’s generally not recommended for automated processes due to password requirements. However, here’s an example of how it might be used:

#!/bin/bash

# backup-script.sh

echo "Starting backup process..."

su -c "tar -czf /backup/$(date +%Y%m%d).tar.gz /home /etc" root << EOF

password_here

EOF

echo "Backup completed"Warning: This approach exposes passwords in scripts and is not secure. Consider using sudo with NOPASSWD configuration for automated tasks instead.

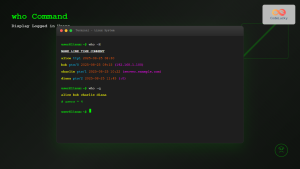

Alternatives to su Command

sudo Command

$ sudo systemctl restart nginx

[sudo] password for user:

$ sudo -i # Interactive root shell

# exitpkexec for GUI Applications

$ pkexec gedit /etc/hostsMonitoring su Usage

System administrators should monitor su usage for security purposes:

$ grep "su:" /var/log/auth.log

Aug 25 10:30:15 server su: pam_unix(su:auth): authentication failure; logname=user uid=1000 euid=0 tty=pts/1 ruser=user rhost= user=root

Aug 25 10:30:20 server su: pam_unix(su:session): session opened for user root by user(uid=1000)Conclusion

The su command is an essential tool for Linux system administration and user management. While powerful, it should be used thoughtfully with proper security considerations. Understanding when to use su versus alternatives like sudo can help maintain system security while providing necessary administrative access.

Remember these key points:

- Use

su -for a complete login environment - Always exit su sessions when finished

- Monitor su usage through system logs

- Consider sudo for better audit trails and granular control

- Never share passwords or hardcode them in scripts

By mastering the su command and following security best practices, you’ll be better equipped to manage Linux systems effectively and securely.