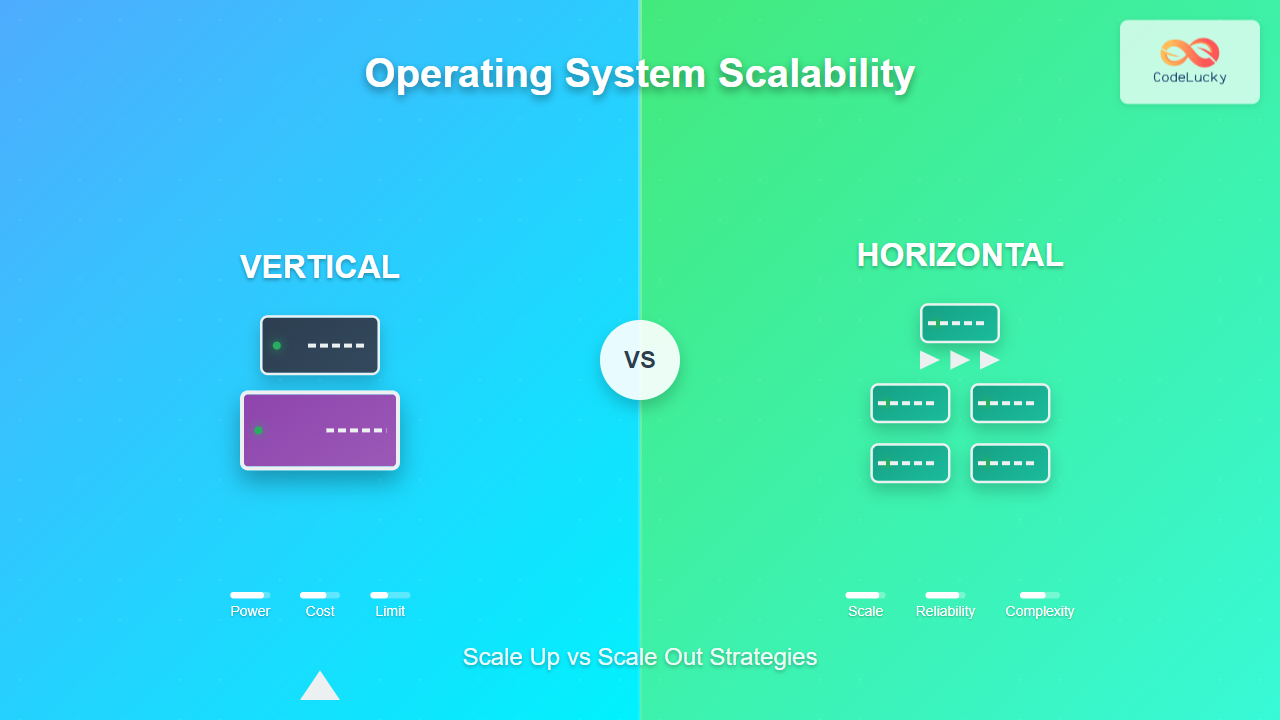

Operating system scalability is a critical factor in modern computing environments, determining how well a system can handle increasing workloads and user demands. As businesses grow and data processing requirements expand, understanding the two primary scaling approaches—horizontal and vertical—becomes essential for system administrators, developers, and IT professionals.

What is Operating System Scalability?

Scalability in operating systems refers to the ability of a system to handle growing amounts of work by adding resources to accommodate increased demand. It’s the measure of how effectively an OS can maintain performance levels as computational requirements expand, whether through more users, larger datasets, or more complex processing tasks.

The concept of scalability encompasses several dimensions:

- Performance scalability – Maintaining response times as load increases

- Capacity scalability – Handling larger volumes of data or users

- Resource scalability – Efficiently utilizing additional hardware resources

- Geographic scalability – Supporting distributed operations across locations

Vertical Scalability (Scale Up)

Vertical scalability, also known as “scaling up,” involves adding more power to existing machines by upgrading hardware components such as CPU, RAM, storage, or network interfaces. This approach focuses on enhancing the capacity of individual systems rather than adding more systems.

Key Characteristics of Vertical Scaling

- Single system enhancement – Upgrades focus on one machine at a time

- Hardware-centric approach – Relies on more powerful components

- Simplified architecture – Maintains existing system topology

- Limited by hardware constraints – Upper bounds determined by available technology

Advantages of Vertical Scaling

Simplicity in Implementation: Vertical scaling requires minimal changes to existing applications and system architecture. Most software can immediately benefit from additional resources without modification.

Reduced Complexity: Managing a single, more powerful system is often simpler than coordinating multiple systems, reducing operational overhead and potential failure points.

Immediate Performance Gains: Hardware upgrades typically provide instant performance improvements, especially for CPU-intensive or memory-bound applications.

Cost-Effective for Small to Medium Scales: Initial scaling efforts are often more economical through hardware upgrades rather than infrastructure expansion.

Limitations of Vertical Scaling

Hardware Limitations: Physical constraints limit how much a single system can be upgraded. CPU, memory, and storage have maximum capacities that cannot be exceeded.

Single Point of Failure: Concentrating resources in one system creates vulnerability—if that system fails, the entire service becomes unavailable.

Exponential Cost Increase: High-end hardware components become disproportionately expensive, making large-scale vertical scaling economically unfeasible.

Downtime Requirements: Hardware upgrades often require system shutdowns, creating service interruptions.

Vertical Scaling Examples

Database Servers: Upgrading a database server from 32GB to 256GB RAM allows it to cache more data in memory, significantly improving query performance for applications like PostgreSQL or MySQL.

Web Servers: Increasing CPU cores from 4 to 16 cores enables an Apache or Nginx server to handle more concurrent connections and process requests faster.

Application Servers: Adding faster NVMe SSDs to replace traditional hard drives can dramatically reduce application startup times and data access latency.

Horizontal Scalability (Scale Out)

Horizontal scalability, or “scaling out,” involves adding more machines to a resource pool to handle increased load. Instead of making individual systems more powerful, this approach distributes work across multiple systems working in coordination.

Key Characteristics of Horizontal Scaling

- Distributed architecture – Multiple systems work together

- Load distribution – Work is spread across available resources

- Fault tolerance – System continues operating if individual components fail

- Linear scalability potential – Capacity can grow proportionally with added systems

Advantages of Horizontal Scaling

Unlimited Theoretical Growth: Adding more machines provides virtually unlimited scaling potential, constrained only by network capacity and coordination overhead.

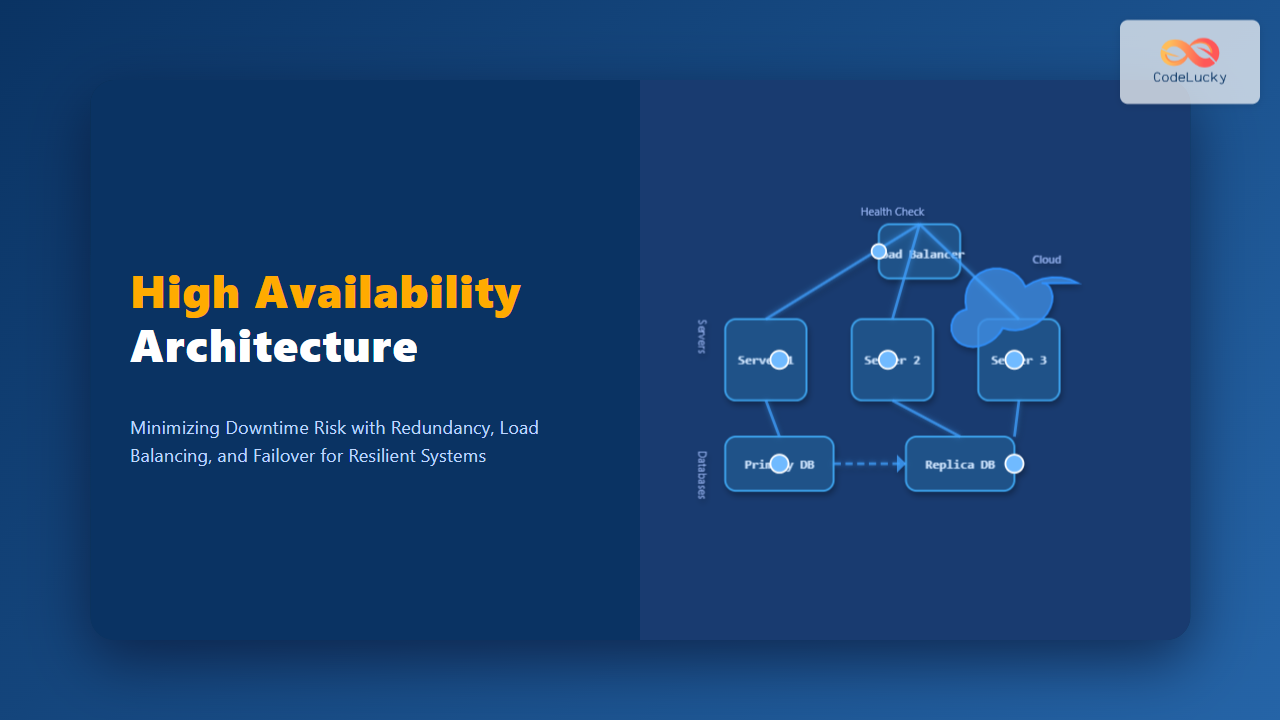

Fault Tolerance: If one machine fails, others continue operating, ensuring service availability and reducing downtime risks.

Cost Effectiveness at Scale: Using commodity hardware is often more economical than purchasing high-end servers, especially for large-scale operations.

Geographic Distribution: Systems can be distributed across different locations, improving performance for geographically dispersed users and providing disaster recovery capabilities.

Challenges of Horizontal Scaling

Increased Complexity: Managing multiple systems requires sophisticated coordination mechanisms, monitoring tools, and deployment strategies.

Network Overhead: Communication between systems introduces latency and potential bottlenecks that don’t exist in single-system architectures.

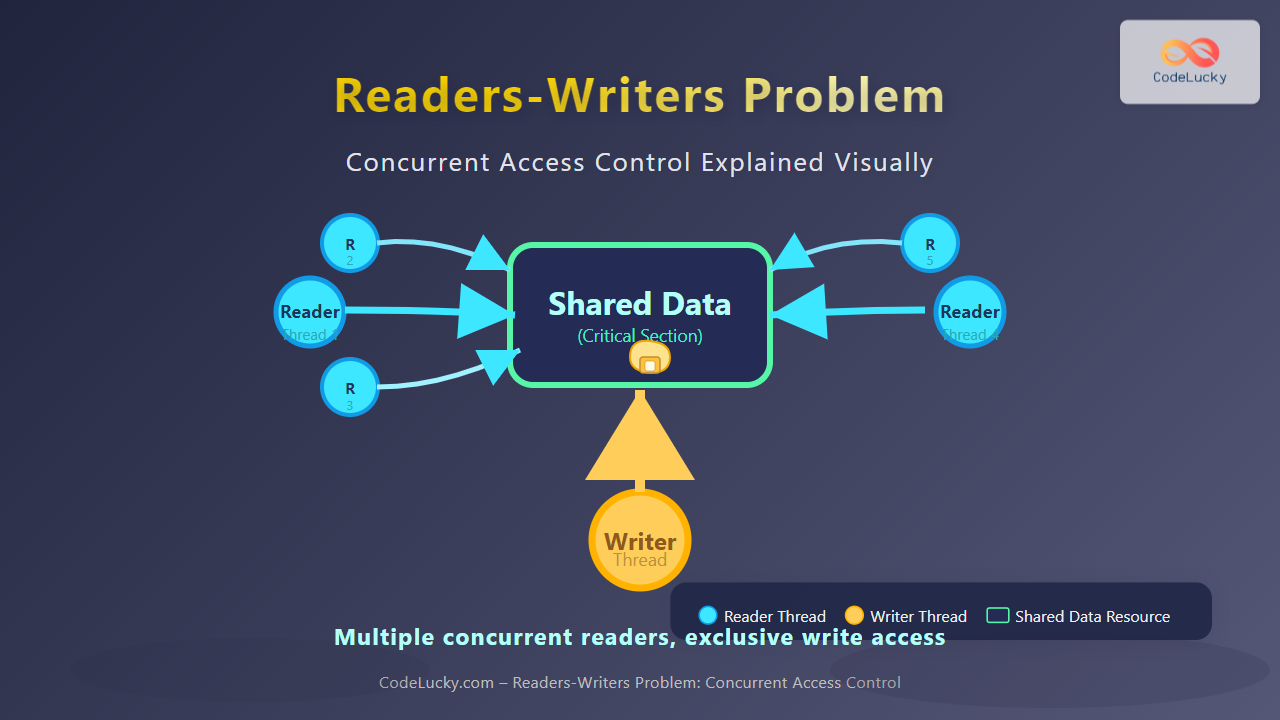

Data Consistency: Maintaining data integrity across multiple systems requires careful design of synchronization and consistency mechanisms.

Application Modifications: Many applications require significant architectural changes to work effectively in distributed environments.

Horizontal Scaling Examples

Web Applications: Companies like Netflix deploy thousands of servers behind load balancers to handle millions of concurrent video streams, with each server handling a subset of users.

Microservices Architecture: Modern applications split functionality into independent services that can scale individually based on demand, like separate services for user authentication, payment processing, and content delivery.

Container Orchestration: Kubernetes clusters automatically add or remove container instances based on load, distributing application components across multiple nodes.

Operating System Support for Scalability

Different operating systems provide varying levels of support for scalability approaches, with specific features and optimizations designed to handle scaling challenges.

Linux Scalability Features

SMP (Symmetric Multiprocessing): Linux effectively utilizes multiple CPU cores through advanced scheduling algorithms and NUMA (Non-Uniform Memory Access) awareness, making it excellent for vertical scaling.

Container Support: Native support for Docker, LXC, and other containerization technologies enables efficient horizontal scaling through lightweight virtualization.

Load Balancing: Built-in tools like HAProxy, Nginx, and kernel-level load balancing support distribute traffic across multiple systems.

Cluster Filesystems: Support for distributed filesystems like GlusterFS and Ceph enables shared storage across horizontally scaled systems.

Windows Server Scalability

Failover Clustering: Windows Server provides built-in clustering capabilities for both high availability and load distribution across multiple servers.

Scale-Out File Server: Enables multiple servers to provide a single namespace for file storage, supporting horizontal scaling of storage resources.

Application Request Routing: IIS includes features for distributing web requests across multiple servers in a farm configuration.

Hyper-V: Virtualization support allows efficient resource utilization and easier horizontal scaling through virtual machine deployment.

Unix Variants and Scalability

Solaris: Features advanced threading models and NUMA optimization, excelling in vertical scaling scenarios with large SMP systems.

AIX: IBM’s Unix variant includes PowerHA for clustering and advanced workload management features for both scaling approaches.

FreeBSD: Offers excellent network performance and jail containerization, making it suitable for both vertical and horizontal scaling scenarios.

Comparing Horizontal vs Vertical Scaling

| Aspect | Vertical Scaling | Horizontal Scaling |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation Complexity | Low – Simple hardware upgrades | High – Requires distributed architecture |

| Maximum Scale Potential | Limited by hardware constraints | Virtually unlimited |

| Fault Tolerance | Single point of failure | High – distributed failure resilience |

| Cost at Small Scale | More economical initially | Higher overhead for small deployments |

| Cost at Large Scale | Exponentially expensive | More cost-effective with commodity hardware |

| Performance Predictability | High – centralized resources | Variable – depends on network and coordination |

| Maintenance Complexity | Low – single system management | High – multiple system coordination |

Hybrid Scaling Strategies

Most modern large-scale systems don’t rely exclusively on one scaling approach. Instead, they implement hybrid strategies that combine both vertical and horizontal scaling to optimize performance, cost, and reliability.

Multi-Tier Scaling

Different application tiers can use different scaling strategies based on their specific requirements:

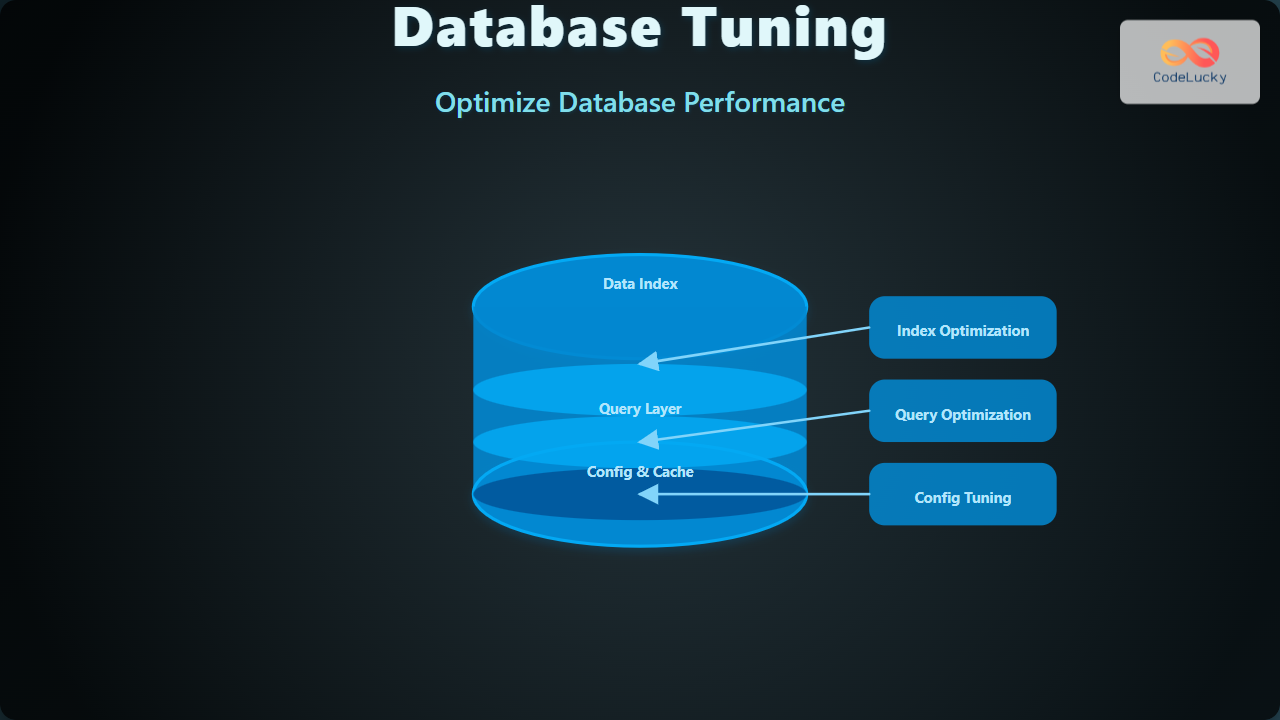

- Database Tier: Often uses vertical scaling for primary databases to maintain consistency, with horizontal scaling for read replicas

- Application Tier: Typically implements horizontal scaling with load-balanced application servers

- Web Tier: Uses horizontal scaling with multiple web servers behind load balancers

- Cache Tier: Implements horizontal scaling with distributed caching solutions like Redis Cluster

Auto-Scaling Implementations

Cloud platforms enable dynamic scaling that automatically adjusts resources based on demand:

Vertical Auto-Scaling: Cloud instances can automatically resize (within limits) based on CPU, memory, or custom metrics.

Horizontal Auto-Scaling: Additional instances are automatically launched or terminated based on load patterns, with load balancers automatically including or excluding them from traffic distribution.

Performance Optimization Techniques

Effective scalability implementation requires careful attention to performance optimization at both the operating system and application levels.

System-Level Optimizations

CPU Affinity and NUMA Awareness: Binding processes to specific CPU cores and memory nodes reduces cache misses and improves performance in vertically scaled systems.

I/O Scheduling: Configuring appropriate I/O schedulers (like CFQ, NOOP, or mq-deadline) based on storage characteristics and workload patterns.

Memory Management: Tuning virtual memory parameters, huge pages, and swap behavior to optimize memory utilization in high-load scenarios.

Network Optimization: Configuring TCP/IP stack parameters, buffer sizes, and network interface settings to handle increased connection loads.

Application-Level Considerations

Stateless Design: Applications designed without server-side state can more easily scale horizontally, as any server can handle any request.

Connection Pooling: Efficient database and network connection management reduces overhead and improves scalability.

Caching Strategies: Implementing effective caching at multiple levels (application, database, CDN) reduces load on backend systems.

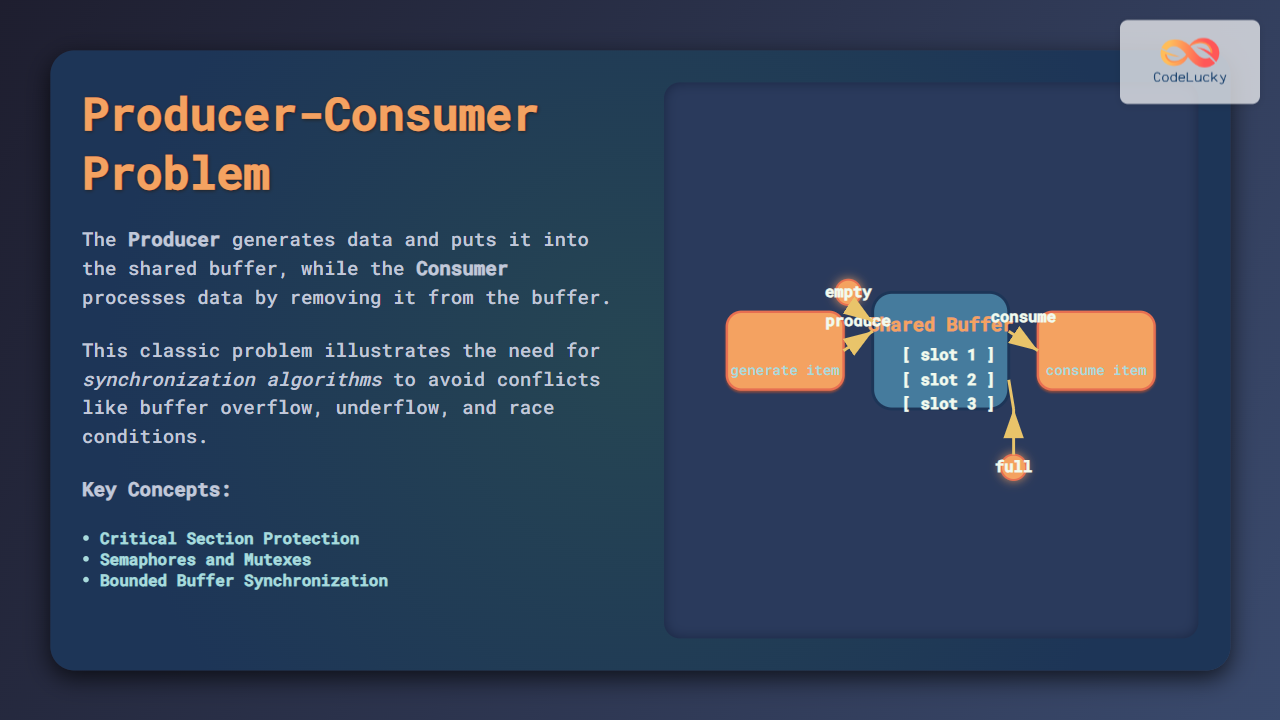

Asynchronous Processing: Using message queues and asynchronous task processing helps distribute work across multiple systems.

Monitoring and Measurement

Effective scalability requires comprehensive monitoring to understand system behavior and identify bottlenecks before they impact performance.

Key Metrics for Vertical Scaling

- CPU Utilization: Per-core usage patterns help identify if additional CPU power would improve performance

- Memory Usage: RAM utilization and swap usage indicate if memory upgrades would be beneficial

- I/O Wait Time: High I/O wait suggests storage upgrades might improve performance

- Network Utilization: Bandwidth usage helps determine if network upgrades are needed

Key Metrics for Horizontal Scaling

- Load Distribution: Even distribution across nodes indicates effective horizontal scaling

- Response Time Variance: Consistent response times across nodes suggest good load balancing

- Network Latency: Inter-node communication delays can impact distributed system performance

- Fault Recovery Time: How quickly the system recovers from node failures

Best Practices and Recommendations

Successful scalability implementation requires following established best practices and making informed decisions based on specific requirements and constraints.

When to Choose Vertical Scaling

- Applications that cannot be easily distributed or require shared memory

- Database systems that need ACID compliance and strong consistency

- Legacy applications not designed for distributed architectures

- Small to medium-scale systems with predictable growth patterns

- Environments where operational complexity must be minimized

When to Choose Horizontal Scaling

- Web applications with stateless components

- Systems requiring high availability and fault tolerance

- Applications with unpredictable or rapidly growing user bases

- Environments where cost optimization at scale is crucial

- Systems that can benefit from geographic distribution

Implementation Guidelines

Start Simple: Begin with vertical scaling for new systems, then transition to horizontal scaling as requirements grow and justify the additional complexity.

Plan for Both: Design applications with both scaling approaches in mind, making it easier to adapt as requirements change.

Monitor Continuously: Implement comprehensive monitoring from the beginning to make informed scaling decisions based on actual usage patterns.

Test Scaling Scenarios: Regularly test both scaling approaches under realistic load conditions to identify potential issues before they impact production.

Consider Cloud Solutions: Modern cloud platforms provide managed services that can simplify both vertical and horizontal scaling implementations.

Future Trends in OS Scalability

The landscape of operating system scalability continues to evolve with emerging technologies and changing computational demands.

Container Orchestration: Kubernetes and similar platforms are making horizontal scaling more accessible and automated, reducing the complexity traditionally associated with distributed systems.

Serverless Computing: Function-as-a-Service platforms abstract scalability concerns, automatically scaling individual functions based on demand without requiring infrastructure management.

Edge Computing: Distributed computing at network edges requires new approaches to horizontal scaling that account for varying resources and network conditions.

AI-Driven Auto-Scaling: Machine learning algorithms are increasingly used to predict scaling needs and automatically adjust resources before performance issues occur.

Hardware Innovations: New processor architectures, memory technologies, and storage solutions continue to push the boundaries of vertical scaling possibilities.

Understanding both horizontal and vertical scalability approaches enables system architects and administrators to make informed decisions that balance performance, cost, and complexity. The most successful systems often combine both strategies, using vertical scaling where appropriate and horizontal scaling where it provides the greatest benefit. As technology continues to evolve, the tools and techniques for implementing scalable systems will continue to improve, but the fundamental principles of matching scaling strategies to specific requirements will remain constant.