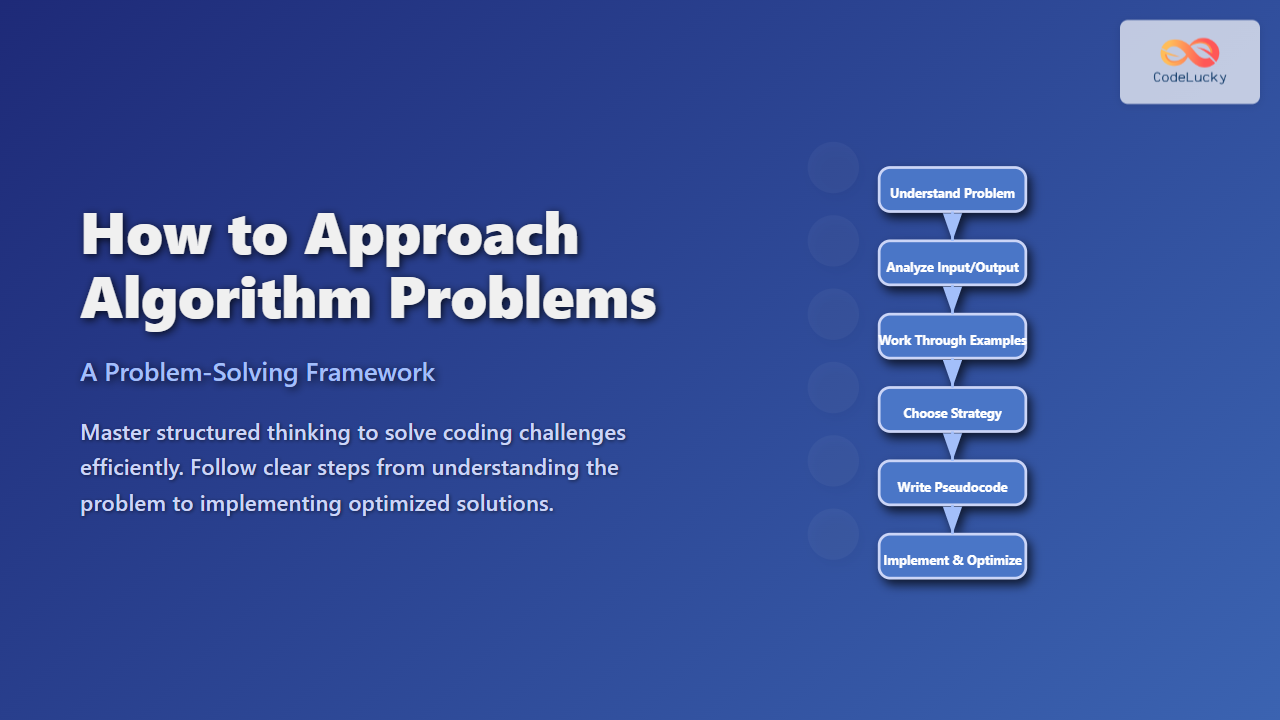

Memory fragmentation is one of the most critical challenges in operating system memory management, directly impacting system performance and resource utilization. Understanding the difference between internal and external fragmentation is essential for system administrators, developers, and anyone working with memory-intensive applications.

This comprehensive guide explores both types of memory fragmentation, their causes, consequences, and practical solutions with detailed examples and visual representations.

What is Memory Fragmentation?

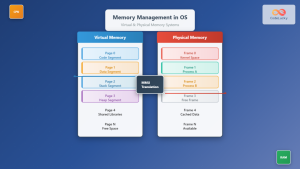

Memory fragmentation occurs when available memory becomes divided into small, non-contiguous blocks, making it difficult or impossible to allocate larger chunks of memory even when sufficient total memory is available. This phenomenon leads to memory waste and degraded system performance.

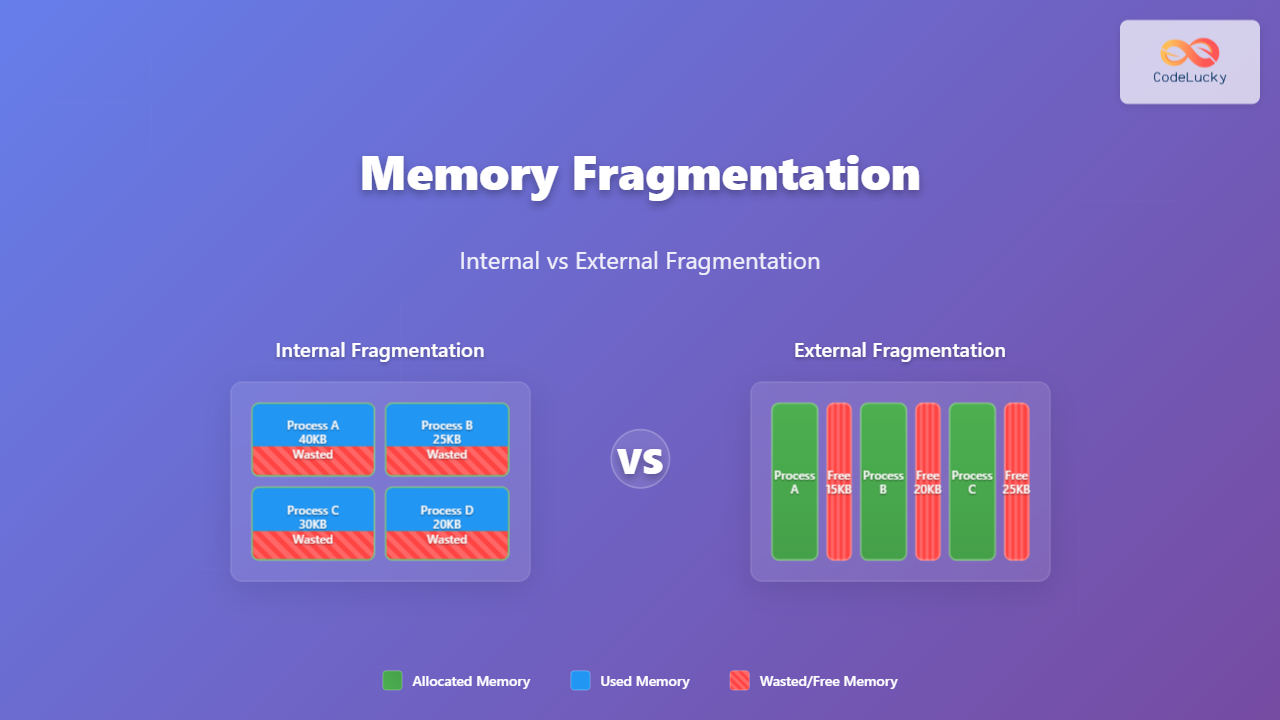

There are two primary types of memory fragmentation:

- Internal Fragmentation – Wasted space within allocated memory blocks

- External Fragmentation – Wasted space between allocated memory blocks

Internal Fragmentation Explained

Internal fragmentation occurs when allocated memory blocks contain unused space that cannot be utilized by other processes. This happens when the allocated memory size exceeds the actual memory requirement of a process.

Causes of Internal Fragmentation

Internal fragmentation primarily occurs in:

- Fixed Partition Memory Management – When processes are allocated fixed-size partitions regardless of their actual memory needs

- Paging Systems – When the last page of a process doesn’t fully utilize the entire page frame

- Memory Alignment Requirements – When memory must be allocated in specific byte boundaries

Internal Fragmentation Example

Consider a system with fixed partitions of 100KB each:

In this scenario, three processes waste a total of 135KB (40KB + 25KB + 70KB) out of 300KB allocated memory, resulting in 45% memory waste due to internal fragmentation.

Calculating Internal Fragmentation

The formula for internal fragmentation is:

Internal Fragmentation = Allocated Memory – Used Memory

// Example calculation

int allocated_memory = 100; // KB

int used_memory = 60; // KB

int internal_fragmentation = allocated_memory - used_memory;

printf("Internal Fragmentation: %d KB\n", internal_fragmentation);

// Output: Internal Fragmentation: 40 KBExternal Fragmentation Explained

External fragmentation occurs when free memory is divided into small, non-contiguous blocks that cannot satisfy allocation requests for larger memory chunks, even though the total free memory might be sufficient.

Causes of External Fragmentation

External fragmentation typically occurs in:

- Dynamic Memory Allocation – When processes of varying sizes are allocated and deallocated randomly

- Variable Partition Schemes – When memory is divided into partitions of different sizes

- Heap Memory Management – In programming languages with dynamic memory allocation

External Fragmentation Example

Consider a memory system with the following allocation pattern:

In this scenario, there are 60KB of free memory (20KB + 15KB + 25KB), but a new process requiring 50KB cannot be allocated because no single contiguous block is large enough, despite having sufficient total free memory.

Real-World External Fragmentation Scenario

// Memory allocation simulation

struct memory_block {

int size;

int is_allocated;

};

// Initial memory state

struct memory_block memory[] = {

{50, 1}, // Process A

{20, 0}, // Free

{80, 1}, // Process B

{15, 0}, // Free

{60, 1}, // Process C

{25, 0} // Free

};

// Attempting to allocate 50KB

int request_size = 50;

int total_free = 20 + 15 + 25; // 60KB total free

// Cannot allocate despite sufficient total memory!Comparison: Internal vs External Fragmentation

| Aspect | Internal Fragmentation | External Fragmentation |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Within allocated blocks | Between allocated blocks |

| Primary Cause | Fixed partition sizes | Variable allocation patterns |

| Memory Waste | Unused space in allocated blocks | Unusable free space fragments |

| Common in | Paging systems, fixed partitions | Dynamic allocation, segmentation |

| Solution Complexity | Moderate (better allocation) | High (defragmentation needed) |

Solutions for Internal Fragmentation

1. Variable Partition Allocation

Instead of fixed partitions, allocate memory blocks that exactly match process requirements:

// Dynamic allocation approach

void* allocate_exact_size(int required_size) {

return malloc(required_size); // Allocates exactly what's needed

}

// Usage

int process_memory_need = 60; // KB

void* allocated_memory = allocate_exact_size(process_memory_need);

// No internal fragmentation!2. Paging with Optimal Page Sizes

Choose page sizes that minimize waste for typical process sizes:

- Small pages – Reduce internal fragmentation but increase overhead

- Large pages – Reduce overhead but increase internal fragmentation

- Variable page sizes – Balance between overhead and fragmentation

3. Memory Pool Allocation

Pre-allocate memory pools of common sizes:

// Memory pool for common allocation sizes

struct memory_pool {

void* pool_32KB;

void* pool_64KB;

void* pool_128KB;

};

// Allocate from appropriate pool

void* allocate_from_pool(int size) {

if (size <= 32) return get_from_pool_32KB();

else if (size <= 64) return get_from_pool_64KB();

else if (size <= 128) return get_from_pool_128KB();

else return malloc(size); // Fallback to dynamic allocation

}Solutions for External Fragmentation

1. Compaction (Defragmentation)

Relocate allocated blocks to create larger contiguous free spaces:

2. Memory Allocation Algorithms

Best Fit Algorithm:

// Best fit allocation - minimizes waste

int best_fit_allocate(int request_size, struct memory_block* memory, int blocks) {

int best_index = -1;

int best_size = INT_MAX;

for (int i = 0; i < blocks; i++) {

if (!memory[i].is_allocated &&

memory[i].size >= request_size &&

memory[i].size < best_size) {

best_size = memory[i].size;

best_index = i;

}

}

if (best_index != -1) {

memory[best_index].is_allocated = 1;

return best_index;

}

return -1; // Allocation failed

}First Fit Algorithm:

// First fit allocation - fastest allocation

int first_fit_allocate(int request_size, struct memory_block* memory, int blocks) {

for (int i = 0; i < blocks; i++) {

if (!memory[i].is_allocated && memory[i].size >= request_size) {

memory[i].is_allocated = 1;

return i;

}

}

return -1; // Allocation failed

}3. Buddy System Algorithm

The buddy system reduces external fragmentation by splitting and merging memory blocks in powers of 2:

// Buddy system implementation concept

struct buddy_block {

int size;

int is_free;

struct buddy_block* buddy;

};

// Split block for smaller allocation

void split_block(struct buddy_block* block, int target_size) {

if (block->size <= target_size) return;

// Create buddy blocks of half size

int half_size = block->size / 2;

struct buddy_block* buddy1 = create_block(half_size);

struct buddy_block* buddy2 = create_block(half_size);

buddy1->buddy = buddy2;

buddy2->buddy = buddy1;

}Performance Impact of Memory Fragmentation

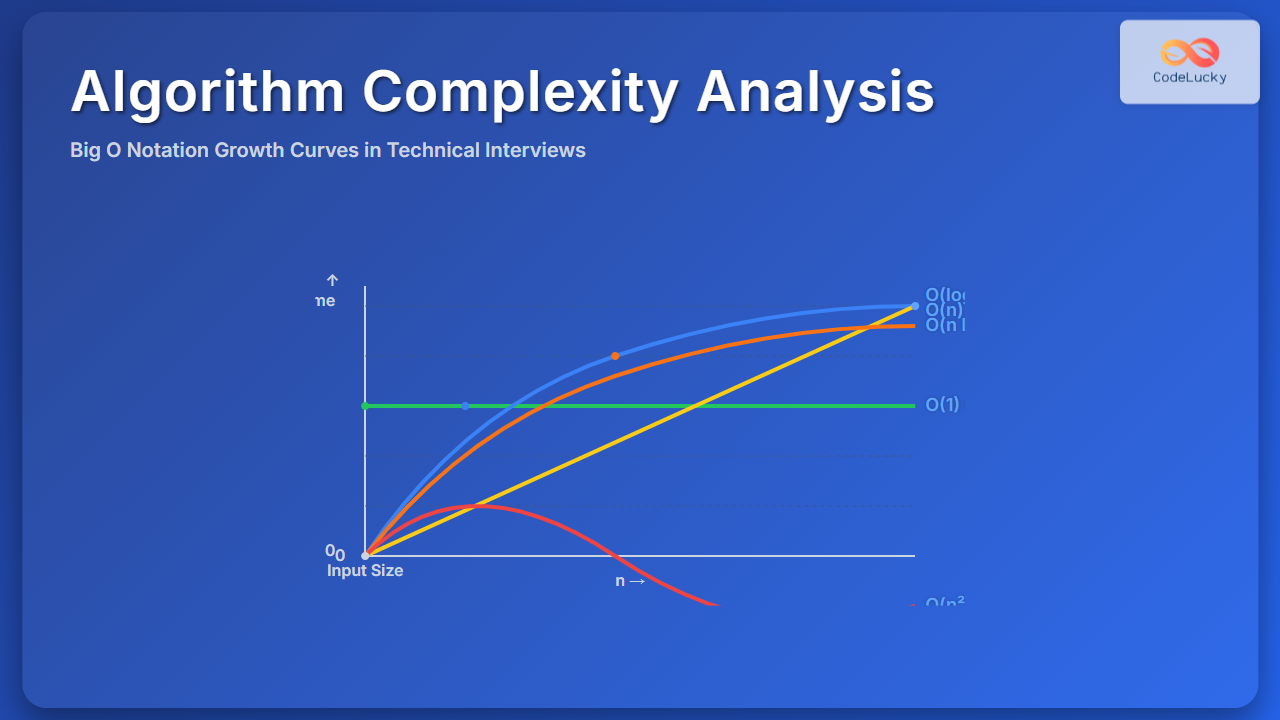

Memory fragmentation significantly impacts system performance:

Internal Fragmentation Impact

- Memory Waste – Up to 50% memory waste in worst-case scenarios

- Reduced Multiprogramming – Fewer processes can run simultaneously

- Poor Memory Utilization – System appears to have less available memory

External Fragmentation Impact

- Allocation Failures – Processes fail to get memory despite availability

- Increased Search Time – Longer time to find suitable memory blocks

- System Thrashing – Excessive swapping due to fragmented memory

Performance Measurement Example

// Measuring fragmentation impact

struct fragmentation_metrics {

int total_memory;

int allocated_memory;

int free_memory;

int largest_free_block;

double internal_fragmentation_ratio;

double external_fragmentation_ratio;

};

void calculate_fragmentation(struct fragmentation_metrics* metrics) {

// Internal fragmentation ratio

metrics->internal_fragmentation_ratio =

(double)(metrics->allocated_memory - actual_used_memory) /

metrics->allocated_memory;

// External fragmentation ratio

metrics->external_fragmentation_ratio =

1.0 - (double)metrics->largest_free_block / metrics->free_memory;

printf("Internal Fragmentation: %.2f%%\n",

metrics->internal_fragmentation_ratio * 100);

printf("External Fragmentation: %.2f%%\n",

metrics->external_fragmentation_ratio * 100);

}Modern Operating System Approaches

Contemporary operating systems employ sophisticated techniques to minimize fragmentation:

Linux Memory Management

- Slab Allocator – Reduces internal fragmentation for kernel objects

- Buddy System – Manages page-level external fragmentation

- Virtual Memory – Allows non-contiguous physical memory allocation

Windows Memory Management

- Heap Manager – Multiple heaps to reduce fragmentation

- Large Page Support – Minimizes page table overhead

- Memory Compression – Increases effective memory availability

Best Practices for Minimizing Fragmentation

For System Administrators

- Monitor Memory Usage – Regular fragmentation analysis

- Optimize Page Sizes – Balance between overhead and waste

- Schedule Defragmentation – During low-usage periods

- Configure Memory Pools – For applications with predictable allocation patterns

For Developers

- Use Memory Pools – For frequent same-size allocations

- Implement Object Recycling – Reuse allocated objects

- Align Memory Access – Follow platform-specific alignment requirements

- Profile Memory Usage – Identify fragmentation hotspots

// Developer best practice example

class MemoryManager {

private:

std::vector memory_pools[10]; // Different size pools

public:

void* allocate(size_t size) {

int pool_index = get_pool_index(size);

if (!memory_pools[pool_index].empty()) {

// Reuse from pool - prevents fragmentation

void* ptr = memory_pools[pool_index].back();

memory_pools[pool_index].pop_back();

return ptr;

}

return malloc(size); // Fallback to system allocation

}

void deallocate(void* ptr, size_t size) {

int pool_index = get_pool_index(size);

memory_pools[pool_index].push_back(ptr); // Return to pool

}

}; Conclusion

Understanding memory fragmentation is crucial for optimal system performance and resource utilization. Internal fragmentation wastes space within allocated blocks and is best addressed through dynamic allocation and appropriate partition sizing. External fragmentation creates unusable gaps between allocations and requires more sophisticated solutions like compaction and advanced allocation algorithms.

Modern operating systems implement multiple strategies to combat both types of fragmentation, including buddy systems, memory pools, and virtual memory management. By applying the principles and techniques outlined in this guide, system administrators and developers can significantly improve memory utilization and overall system performance.

The key to successful memory management lies in understanding your system’s allocation patterns and choosing appropriate strategies based on the specific requirements and constraints of your environment.

- What is Memory Fragmentation?

- Internal Fragmentation Explained

- External Fragmentation Explained

- Comparison: Internal vs External Fragmentation

- Solutions for Internal Fragmentation

- Solutions for External Fragmentation

- Performance Impact of Memory Fragmentation

- Modern Operating System Approaches

- Best Practices for Minimizing Fragmentation

- Conclusion