Introduction to Linux Virtual Memory

Virtual memory is one of the most critical components of modern operating systems, and Linux implements it with exceptional sophistication. This comprehensive guide explores how Linux manages memory through virtual memory implementation, providing system administrators and developers with deep insights into memory allocation strategies, paging mechanisms, and performance optimization techniques.

Linux virtual memory abstraction allows processes to access more memory than physically available, enables memory protection between processes, and provides efficient memory sharing mechanisms. Understanding these concepts is essential for optimizing system performance and troubleshooting memory-related issues.

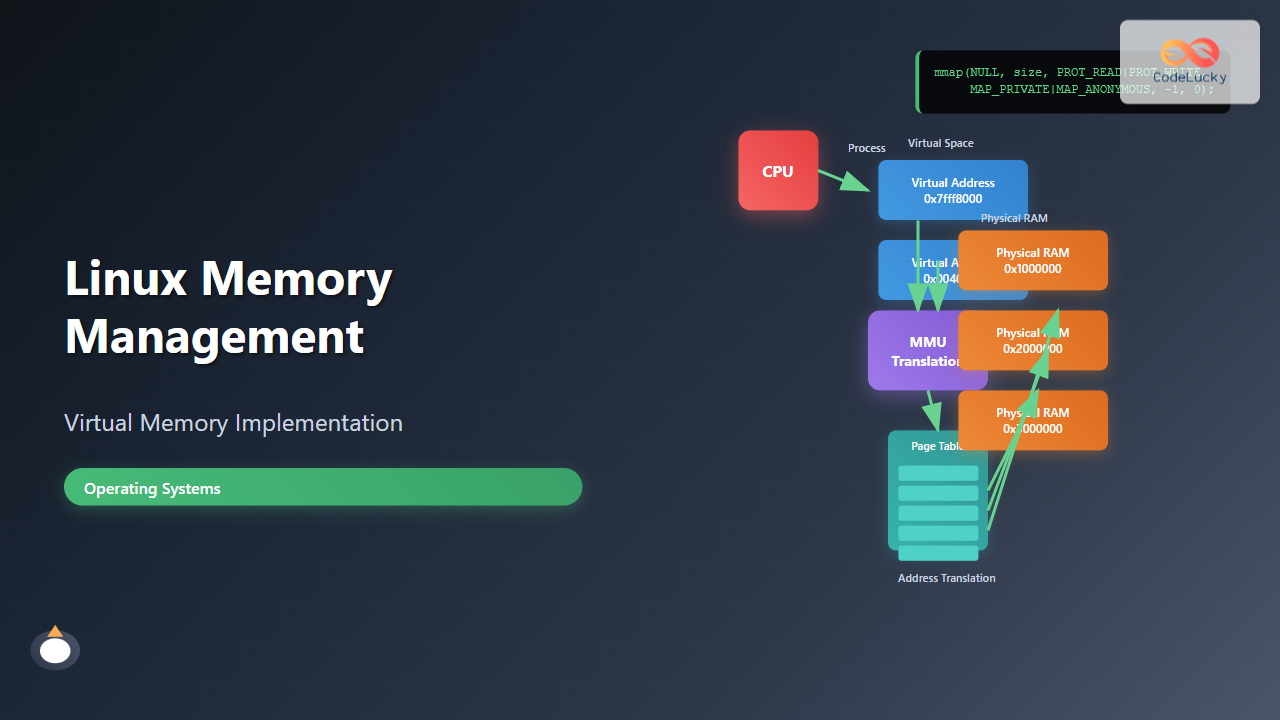

Virtual Memory Architecture Overview

Linux implements a three-level virtual memory architecture that separates logical addresses from physical addresses. This architecture consists of the Memory Management Unit (MMU), page tables, and the kernel’s memory management subsystem.

The virtual address space in Linux is divided into user space and kernel space. On 32-bit systems, the typical split allocates 3GB to user space (0x00000000 to 0xBFFFFFFF) and 1GB to kernel space (0xC0000000 to 0xFFFFFFFF). On 64-bit systems, this limitation is virtually eliminated with much larger address spaces.

Memory Mapping and Address Translation

Linux uses a sophisticated page-based memory management system where memory is divided into fixed-size pages (typically 4KB on x86 architectures). The Memory Management Unit (MMU) translates virtual addresses to physical addresses using page tables.

Page Table Structure

Linux implements a multi-level page table structure to efficiently manage large address spaces. On x86-64 systems, Linux uses a four-level page table hierarchy:

- Page Global Directory (PGD) – Top-level page table

- Page Upper Directory (PUD) – Second-level page table

- Page Middle Directory (PMD) – Third-level page table

- Page Table Entry (PTE) – Final-level containing physical address

Examining Virtual Memory Mappings

You can examine a process’s virtual memory layout using the /proc/[pid]/maps file. Here’s a practical example:

# View memory mappings for the current shell process

cat /proc/$$/maps

# Example output:

# 55f8d4e6b000-55f8d4e6c000 r--p 00000000 08:01 123456 /bin/bash

# 55f8d4e6c000-55f8d4f49000 r-xp 00001000 08:01 123456 /bin/bash

# 55f8d4f49000-55f8d4f7c000 r--p 000de000 08:01 123456 /bin/bash

# 55f8d4f7d000-55f8d4f81000 rw-p 00111000 08:01 123456 /bin/bash

# 7f5a2c000000-7f5a2c021000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [heap]

# 7fff8e5dd000-7fff8e5fe000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [stack]

Each line in the maps file shows:

- Address range – Virtual memory addresses

- Permissions – r(read), w(write), x(execute), p(private)

- Offset – File offset for mapped files

- Device – Device ID

- Inode – Inode number

- Pathname – Associated file or memory region type

Memory Allocation Mechanisms

Linux provides multiple memory allocation mechanisms to handle different use cases efficiently. These mechanisms work together to provide optimal memory management for various workloads.

SLUB Allocator

The SLUB (Simple List of Unused Blocks) allocator handles small memory allocations efficiently. It maintains per-CPU caches and object-specific caches to minimize allocation overhead.

# View SLUB allocator statistics

cat /proc/slabinfo | head -10

# Example output showing cache information:

# slabinfo - version: 2.1

# # name <active_objs> <num_objs> <objsize> <objperslab> <pagesperslab>

# ext4_inode_cache 25840 26208 1048 31 8

# dentry 89234 89472 192 21 1

# inode_cache 18650 19040 600 26 4

Buddy Allocator

The buddy allocator manages larger memory chunks by maintaining free page lists organized by size. It uses a binary buddy system to efficiently allocate and deallocate contiguous memory pages.

# View buddy allocator information

cat /proc/buddyinfo

# Example output:

# Node 0, zone DMA 2 1 1 0 2 1 1 0 1 1 3

# Node 0, zone DMA32 48 38 23 11 4 3 2 2 2 1 408

# Node 0, zone Normal 124 115 87 55 33 16 8 4 2 1 1847

Paging and Swap Management

Linux implements demand paging and swap management to handle memory pressure efficiently. When physical memory becomes scarce, the kernel can move less frequently used pages to swap space on storage devices.

Monitoring Swap Activity

Understanding swap activity is crucial for system performance tuning. Here are practical examples of monitoring swap usage:

# Check current swap usage

free -h

# Example output:

# total used free shared buff/cache available

# Mem: 15Gi 2.1Gi 8.2Gi 186Mi 5.4Gi 13Gi

# Swap: 2.0Gi 0B 2.0Gi

# Monitor swap activity in real-time

vmstat 1

# Example output showing swap in/out:

# procs -----------memory---------- ---swap-- -----io---- -system-- ------cpu-----

# r b swpd free buff cache si so bi bo in cs us sy id wa st

# 2 0 0 8425372 156789 5421384 0 0 4 12 89 156 1 1 98 0 0

# Check swap configuration

swapon --show

# Example output:

# NAME TYPE SIZE USED PRIO

# /dev/sda2 partition 2G 0B -2

Configuring Swap Behavior

Linux provides the vm.swappiness parameter to control swap aggressiveness:

# Check current swappiness value

cat /proc/sys/vm/swappiness

# Set swappiness (0-100, default usually 60)

# Lower values = less aggressive swapping

echo 10 > /proc/sys/vm/swappiness

# Make permanent in /etc/sysctl.conf

echo "vm.swappiness=10" >> /etc/sysctl.conf

Memory Zones and NUMA

Linux organizes physical memory into zones to handle hardware limitations and optimize memory access patterns. On modern systems, you’ll typically encounter DMA, DMA32, Normal, and Movable zones.

NUMA Awareness

On Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA) systems, Linux implements NUMA-aware memory allocation to optimize performance:

# Check NUMA topology

numactl --hardware

# Example output:

# available: 2 nodes (0-1)

# node 0 cpus: 0 2 4 6

# node 0 size: 8192 MB

# node 0 free: 6234 MB

# node 1 cpus: 1 3 5 7

# node 1 size: 8192 MB

# node 1 free: 7891 MB

# View per-node memory statistics

cat /proc/meminfo | grep -E "(Node|MemTotal|MemFree)"

# Run process with specific NUMA policy

numactl --cpubind=0 --membind=0 ./memory_intensive_app

Virtual Memory Areas (VMAs)

Linux manages virtual memory through Virtual Memory Areas (VMAs), which represent contiguous ranges of virtual addresses with similar properties. Each VMA contains information about memory permissions, backing store, and memory management policies.

Analyzing VMA Information

You can examine detailed VMA information using the /proc/[pid]/smaps file:

# View detailed memory mapping information

cat /proc/$$/smaps | head -20

# Example output showing VMA details:

# 55f8d4e6b000-55f8d4e6c000 r--p 00000000 08:01 123456 /bin/bash

# Size: 4 kB

# Rss: 4 kB

# Pss: 4 kB

# Shared_Clean: 0 kB

# Shared_Dirty: 0 kB

# Private_Clean: 4 kB

# Private_Dirty: 0 kB

# Referenced: 4 kB

# Anonymous: 0 kB

# Swap: 0 kB

# KernelPageSize: 4 kB

# MMUPageSize: 4 kB

# Locked: 0 kB

# Calculate total memory usage for a process

grep -E "^(Rss|Pss):" /proc/$$/smaps | awk '{sum+=$2} END {print sum " kB"}'

Page Cache and Buffer Management

Linux implements an efficient page cache system that caches frequently accessed files in memory, significantly improving I/O performance. The page cache works transparently with the virtual memory system.

Monitoring Page Cache Usage

# View detailed memory statistics

cat /proc/meminfo | grep -E "(Cached|Buffers|Dirty|Writeback)"

# Example output:

# Buffers: 156789 kB

# Cached: 5421384 kB

# Dirty: 12345 kB

# Writeback: 0 kB

# Monitor page cache hit/miss ratios

sar -B 1 5

# Example output showing paging statistics:

# Average: pgpgin/s pgpgout/s fault/s majflt/s pgfree/s pgscank/s pgscand/s pgsteal/s %vmeff

# Average: 0.12 4.56 2156.78 0.02 1234.56 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

# Clear page cache (use with caution)

echo 3 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches

Memory Protection and Security

Linux implements various memory protection mechanisms to ensure system security and stability. These include Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR), Data Execution Prevention (DEP), and memory access controls.

ASLR Configuration

# Check ASLR status

cat /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

# Values:

# 0 - No randomization

# 1 - Conservative randomization

# 2 - Full randomization (default)

# Temporarily disable ASLR (for debugging)

echo 0 > /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

# View process memory layout changes

for i in {1..3}; do

echo "=== Run $i ==="

/bin/bash -c 'cat /proc/$$/maps | grep stack'

done

Performance Tuning and Optimization

Optimizing Linux virtual memory performance requires understanding workload characteristics and tuning various kernel parameters appropriately.

Key Tuning Parameters

# View current VM tuning parameters

sysctl vm.

# Key parameters to consider:

# vm.dirty_ratio - Percentage of memory that can be dirty before sync

# vm.dirty_background_ratio - Start background writeback at this percentage

# vm.vfs_cache_pressure - Tendency to reclaim directory/inode cache

# Example tuning for high-performance server

cat >> /etc/sysctl.conf << EOF

vm.swappiness=10

vm.dirty_ratio=20

vm.dirty_background_ratio=5

vm.vfs_cache_pressure=50

vm.min_free_kbytes=65536

EOF

# Apply changes

sysctl -p

Memory Pressure Monitoring

# Monitor memory pressure using PSI (Pressure Stall Information)

cat /proc/pressure/memory

# Example output:

# some avg10=0.15 avg60=0.08 avg300=0.03 total=45123456

# full avg10=0.02 avg60=0.01 avg300=0.00 total=12345678

# Set up memory pressure monitoring

echo "memory.pressure some 10 1000" > /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/memory.pressure_level

# Use iostat to monitor paging activity

iostat -x 1

Troubleshooting Memory Issues

Understanding how to diagnose and resolve memory-related problems is essential for system administrators. Linux provides numerous tools and techniques for memory troubleshooting.

Out of Memory (OOM) Analysis

# Check for OOM killer activity in system logs

dmesg | grep -i "killed process"

journalctl | grep -i "out of memory"

# Example OOM killer output:

# Out of memory: Kill process 1234 (chrome) score 856 or sacrifice child

# Killed process 1234 (chrome) total-vm:1234567kB, anon-rss:987654kB, file-rss:12345kB

# Monitor memory usage in real-time

top -o %MEM

# Use pmap to analyze process memory usage

pmap -x [pid]

# Example output:

# Address Kbytes RSS Dirty Mode Mapping

# 0000555555554000 4 4 0 r-xp /bin/cat

# 0000555555755000 4 4 4 r--p /bin/cat

# 0000555555756000 4 4 4 rw-p /bin/cat

Memory Leak Detection

# Monitor process memory growth over time

while true; do

date

cat /proc/[pid]/status | grep -E "(VmSize|VmRSS|VmData)"

sleep 60

done

# Use valgrind for detailed memory leak analysis

valgrind --tool=memcheck --leak-check=full ./your_program

# Monitor system-wide memory allocation

cat /proc/meminfo

watch -n 1 'cat /proc/meminfo | head -10'

Advanced Virtual Memory Features

Linux implements several advanced virtual memory features that provide enhanced functionality for specific use cases.

Huge Pages

Huge pages reduce TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer) pressure for applications that use large amounts of memory:

# Check huge page configuration

cat /proc/meminfo | grep -i huge

# Example output:

# AnonHugePages: 102400 kB

# ShmemHugePages: 0 kB

# HugePages_Total: 10

# HugePages_Free: 10

# HugePages_Rsvd: 0

# HugePages_Surp: 0

# Hugepagesize: 2048 kB

# Configure huge pages

echo 100 > /proc/sys/vm/nr_hugepages

# Check transparent huge page status

cat /sys/kernel/mm/transparent_hugepage/enabled

# Mount huge page filesystem

mkdir /mnt/hugepages

mount -t hugetlbfs nodev /mnt/hugepages

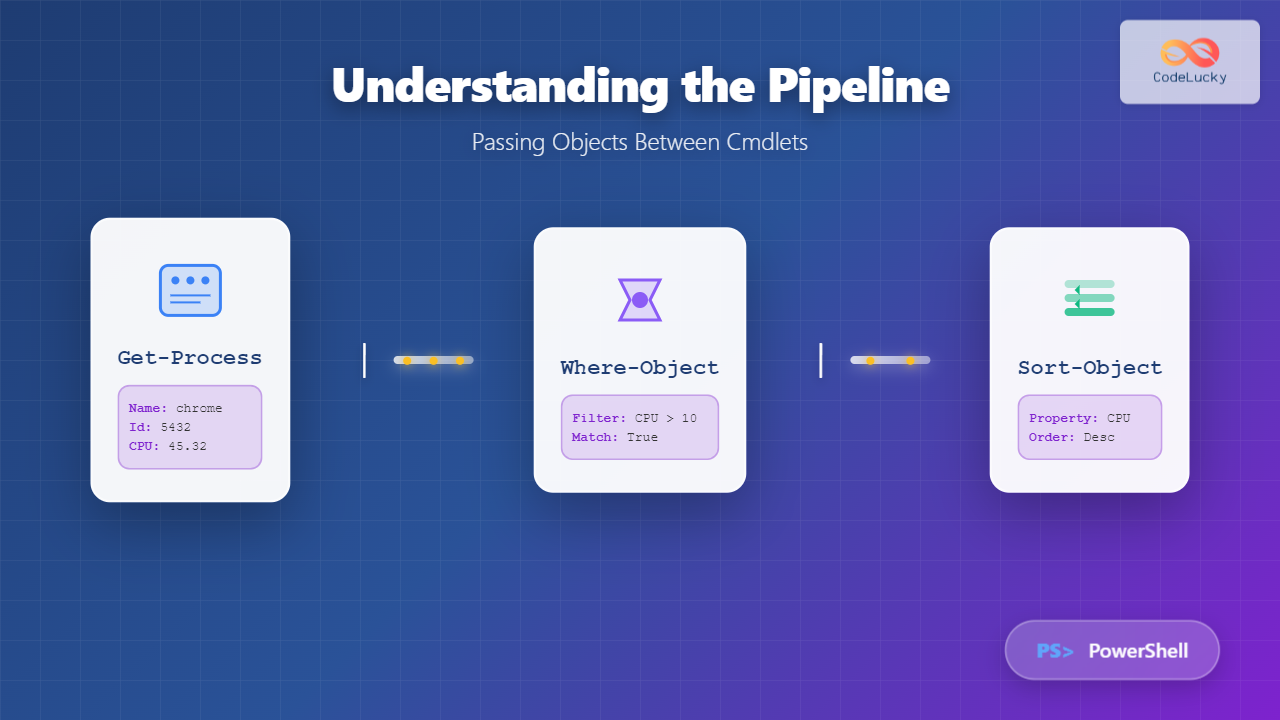

Memory Mapping and mmap

The mmap system call provides powerful memory mapping capabilities that integrate directly with the virtual memory system:

// Example: Memory mapping a file

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int fd = open("data.txt", O_RDONLY);

struct stat sb;

fstat(fd, &sb);

void *mapped = mmap(NULL, sb.st_size, PROT_READ, MAP_SHARED, fd, 0);

if (mapped == MAP_FAILED) {

perror("mmap");

exit(1);

}

// Access file through memory mapping

char first_byte = ((char*)mapped)[0];

// Cleanup

munmap(mapped, sb.st_size);

close(fd);

Conclusion

Linux virtual memory implementation represents one of the most sophisticated memory management systems in modern operating systems. By understanding the concepts covered in this guide – from basic virtual memory architecture to advanced features like NUMA awareness and huge pages – system administrators and developers can optimize their applications and systems for better performance and reliability.

The key takeaways include understanding how virtual address translation works, monitoring memory usage effectively, tuning kernel parameters for specific workloads, and leveraging advanced features when appropriate. Regular monitoring and proactive memory management practices will help maintain optimal system performance and prevent memory-related issues before they impact system stability.

As systems continue to grow in complexity and memory requirements increase, mastering Linux virtual memory management becomes increasingly critical for anyone working with Linux systems in production environments.