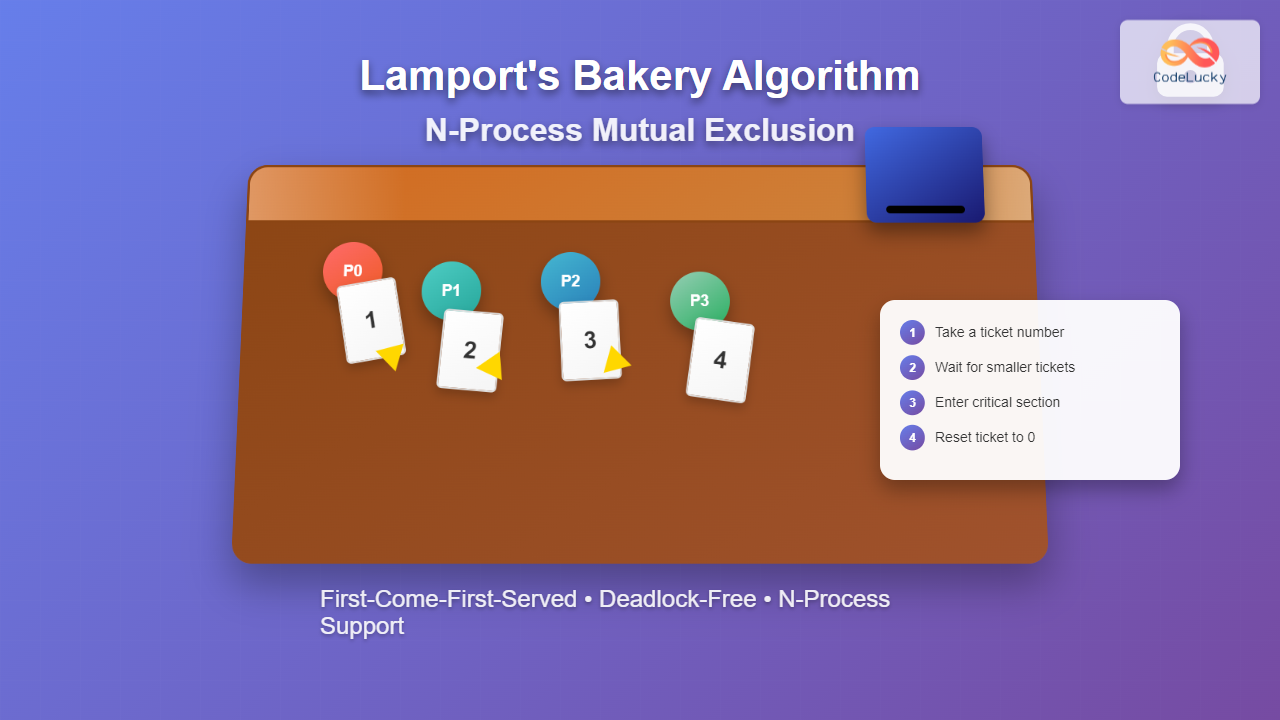

Lamport’s Bakery Algorithm stands as one of the most elegant solutions to the N-process mutual exclusion problem in concurrent programming. Named after computer scientist Leslie Lamport, this algorithm ensures that multiple processes can safely access shared resources without conflicts, using a ticket-based approach similar to taking numbers at a bakery counter.

Understanding Mutual Exclusion

Before diving into the Bakery Algorithm, let’s establish what mutual exclusion means in concurrent systems. When multiple processes need to access a shared resource (like a file, database, or memory location), we must ensure that only one process can access it at a time. This prevents race conditions and maintains data consistency.

The mutual exclusion problem requires satisfying three key properties:

- Mutual Exclusion: Only one process can be in the critical section at any time

- Progress: If no process is in the critical section, one of the waiting processes must eventually enter

- Bounded Waiting: No process should wait indefinitely to enter the critical section

The Bakery Analogy

Imagine visiting a busy bakery where customers take numbered tickets and wait to be served in order. Lamport’s algorithm works similarly:

- Each process wanting to enter the critical section takes a “ticket” (a number)

- The process with the smallest ticket number gets served first

- If two processes have the same number, the process with the smaller ID goes first

- After leaving the critical section, the process discards its ticket

Algorithm Components

The Bakery Algorithm uses two main data structures for N processes:

- choosing[N]: Boolean array indicating if a process is currently choosing a ticket

- ticket[N]: Integer array storing each process’s current ticket number

Both arrays are shared among all processes and initialized to false and 0 respectively.

Detailed Algorithm Steps

Here’s the complete Bakery Algorithm for process i:

// Entry Section

choosing[i] = true;

ticket[i] = max(ticket[0], ticket[1], ..., ticket[n-1]) + 1;

choosing[i] = false;

for (j = 0; j < n; j++) {

while (choosing[j]) { /* wait */ }

while ((ticket[j] != 0) &&

((ticket[j] < ticket[i]) ||

((ticket[j] == ticket[i]) && (j < i)))) {

/* wait */

}

}

// Critical Section

// ... critical code here ...

// Exit Section

ticket[i] = 0;

// Remainder Section

// ... non-critical code ...

Step-by-Step Breakdown

Step 1: Taking a Ticket

When a process wants to enter the critical section, it sets choosing[i] = true to indicate it’s selecting a number. It then chooses a ticket number one greater than the maximum of all current tickets.

Step 2: Waiting Phase

The process waits for two conditions:

- No other process is currently choosing a number

- All processes with smaller tickets (or same ticket but smaller ID) have finished

Step 3: Critical Section Access

Once conditions are met, the process enters the critical section safely.

Step 4: Exit

After completing critical work, the process sets its ticket to 0, indicating it’s no longer interested in the critical section.

Example Execution

Let’s trace through an example with 3 processes (P0, P1, P2):

Implementation in C

Here’s a practical implementation of the Bakery Algorithm:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

#define N 5 // Number of processes

// Shared variables

volatile bool choosing[N] = {false};

volatile int ticket[N] = {0};

int shared_counter = 0;

// Function to find maximum ticket number

int max_ticket() {

int max = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

if (ticket[i] > max) {

max = ticket[i];

}

}

return max;

}

// Bakery algorithm implementation

void* process(void* arg) {

int process_id = *(int*)arg;

for (int iteration = 0; iteration < 3; iteration++) {

// Entry Section

choosing[process_id] = true;

ticket[process_id] = max_ticket() + 1;

choosing[process_id] = false;

// Wait for turn

for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) {

while (choosing[j]) { /* busy wait */ }

while ((ticket[j] != 0) &&

((ticket[j] < ticket[process_id]) ||

((ticket[j] == ticket[process_id]) && (j < process_id)))) {

/* busy wait */

}

}

// Critical Section

printf("Process %d entering critical section\n", process_id);

int local_counter = shared_counter;

sleep(1); // Simulate some work

shared_counter = local_counter + 1;

printf("Process %d: counter = %d\n", process_id, shared_counter);

printf("Process %d exiting critical section\n", process_id);

// Exit Section

ticket[process_id] = 0;

// Remainder Section

sleep(1); // Simulate non-critical work

}

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t threads[N];

int process_ids[N];

// Create processes

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

process_ids[i] = i;

pthread_create(&threads[i], NULL, process, &process_ids[i]);

}

// Wait for all processes to complete

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

pthread_join(threads[i], NULL);

}

printf("Final counter value: %d\n", shared_counter);

return 0;

}

Expected Output

Process 0 entering critical section

Process 0: counter = 1

Process 0 exiting critical section

Process 1 entering critical section

Process 1: counter = 2

Process 1 exiting critical section

Process 2 entering critical section

Process 2: counter = 3

Process 2 exiting critical section

...

Final counter value: 15

Properties and Correctness

The Bakery Algorithm satisfies all required properties for mutual exclusion:

Mutual Exclusion

The algorithm ensures mutual exclusion through its ticket comparison mechanism. Two processes cannot have identical tickets with the same process ID, and the lexicographic ordering (ticket[j], j) < (ticket[i], i) creates a total ordering among processes.

Progress and Bounded Waiting

The algorithm guarantees progress because:

- Processes with smaller ticket numbers eventually enter the critical section

- No process holds onto its ticket indefinitely

- The FIFO nature prevents starvation

Bounded waiting is ensured because once a process takes a ticket, at most N-1 other processes can enter the critical section before it gets its turn.

Advantages and Limitations

Advantages

- First-Come-First-Served: Fair ordering based on ticket numbers

- No special hardware: Works with basic read/write operations

- Scalable: Handles any number of processes

- Deadlock-free: No circular waiting conditions

- Starvation-free: Every process eventually gets served

Limitations

- Performance overhead: Busy waiting consumes CPU cycles

- Memory usage: Requires O(N) space for arrays

- Ticket overflow: Ticket numbers can grow very large

- Not suitable for real-time: Unbounded waiting times

Optimizations and Variations

Ticket Reset Optimization

To prevent ticket number overflow, implement periodic resets when all processes have ticket 0:

void reset_tickets_if_needed() {

bool all_zero = true;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

if (ticket[i] != 0) {

all_zero = false;

break;

}

}

if (all_zero) {

// Safe to reset - all processes are in remainder section

// No additional action needed as tickets are already 0

}

}

Fast Path Optimization

Add a quick check for an empty critical section:

bool is_critical_section_empty() {

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

if (ticket[i] != 0) return false;

}

return true;

}

Comparison with Other Algorithms

| Algorithm | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | Hardware Requirements | Fairness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakery Algorithm | O(N) per entry | O(N) | Basic read/write | FIFO |

| Peterson’s Algorithm | O(1) | O(1) | Basic read/write | Alternating (2 processes) |

| Test-and-Set | O(1) | O(1) | Atomic test-and-set | No guarantee |

| Semaphores | O(1) | O(1) | Atomic operations | FIFO (implementation dependent) |

Real-World Applications

The Bakery Algorithm finds applications in:

- Distributed systems: When atomic operations aren’t available across nodes

- Educational purposes: Teaching mutual exclusion concepts

- Embedded systems: Where hardware synchronization primitives are limited

- Fault-tolerant systems: Where software-only solutions are preferred

Common Pitfalls and Debugging

Race Condition in Ticket Selection

The most common mistake is not properly handling the ticket selection phase:

// WRONG - Race condition possible

ticket[i] = max(ticket[0], ..., ticket[n-1]) + 1;

// CORRECT - Use choosing flag

choosing[i] = true;

ticket[i] = max(ticket[0], ..., ticket[n-1]) + 1;

choosing[i] = false;

Incorrect Comparison Logic

Ensure the lexicographic comparison is implemented correctly:

// Check both ticket value AND process ID for ties

while ((ticket[j] != 0) &&

((ticket[j] < ticket[i]) ||

((ticket[j] == ticket[i]) && (j < i)))) {

/* wait */

}

Performance Analysis

The Bakery Algorithm’s performance characteristics:

- Best case: O(1) when no contention exists

- Worst case: O(N) when all processes compete simultaneously

- Average case: O(k) where k is the number of competing processes

- Memory footprint: 2N variables (choosing array + ticket array)

Modern Relevance

While modern systems often use hardware-supported synchronization primitives, the Bakery Algorithm remains relevant for:

- Theoretical understanding: Fundamental concepts in concurrency

- Distributed systems: Software-only synchronization across networks

- Research: Basis for more advanced algorithms

- Education: Clear illustration of mutual exclusion principles

Conclusion

Lamport’s Bakery Algorithm elegantly solves the N-process mutual exclusion problem using only basic read and write operations. Its first-come-first-served fairness, scalability to any number of processes, and freedom from deadlock and starvation make it a cornerstone algorithm in concurrent programming theory.

While it may not be the most efficient solution for high-performance systems, the Bakery Algorithm’s simplicity and correctness properties make it invaluable for understanding mutual exclusion concepts. Its influence can be seen in many modern synchronization mechanisms, and it continues to be relevant in distributed systems where hardware atomic operations aren’t available across network boundaries.

Understanding the Bakery Algorithm provides a solid foundation for tackling more complex synchronization challenges in concurrent and distributed systems programming.