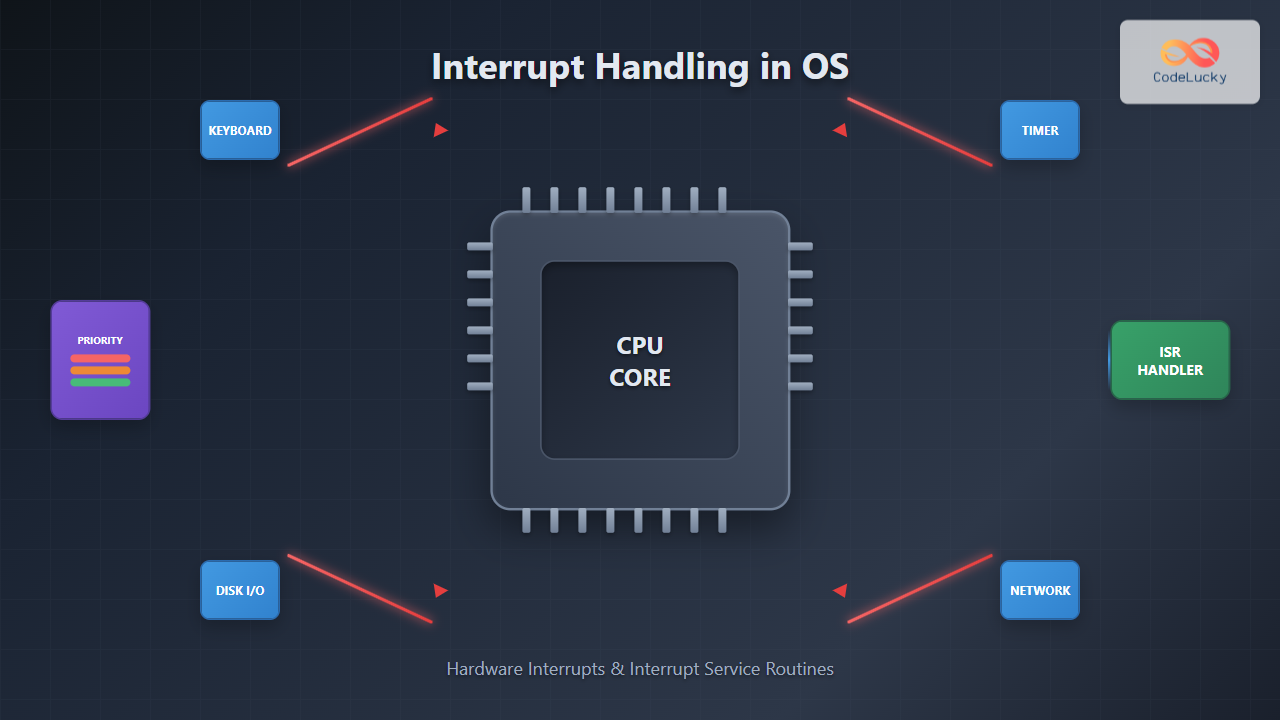

Introduction to Interrupt Handling

Interrupt handling is a fundamental mechanism in operating systems that enables efficient communication between hardware devices and the CPU. When a hardware device needs attention from the processor, it sends an interrupt signal to temporarily suspend the current execution and handle the device’s request through specialized routines called Interrupt Service Routines (ISR).

This mechanism ensures that the CPU can respond to time-critical events without continuously polling hardware devices, making modern computing systems both responsive and efficient.

What are Interrupts?

An interrupt is a signal sent to the processor by hardware or software indicating that an event needs immediate attention. When an interrupt occurs, the processor temporarily stops its current activity and executes a special function called an interrupt handler or ISR.

Types of Interrupts

- Hardware Interrupts: Generated by hardware devices (keyboard, mouse, timer, disk drives)

- Software Interrupts: Generated by executing specific instructions (system calls, exceptions)

- Maskable Interrupts: Can be disabled by the processor

- Non-maskable Interrupts (NMI): Cannot be disabled and must be handled immediately

Hardware Interrupts: The Foundation

Hardware interrupts are signals generated by external devices to request service from the CPU. These interrupts are essential for:

- I/O Operations: Notifying completion of data transfer

- Timer Events: Triggering periodic system activities

- Error Conditions: Reporting hardware failures or exceptions

- User Input: Processing keyboard and mouse events

Common Hardware Interrupt Sources

| Device | IRQ Number | Purpose | Priority |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Timer | IRQ 0 | Clock ticks, scheduling | High |

| Keyboard | IRQ 1 | Key press/release events | Medium |

| Serial Port 1 | IRQ 4 | Serial communication | Medium |

| Hard Disk | IRQ 14 | Disk I/O completion | High |

| Network Card | IRQ 11 | Network packet arrival | High |

Interrupt Service Routines (ISR)

An Interrupt Service Routine is a special function that handles specific interrupt events. ISRs must be carefully designed to be fast, efficient, and non-blocking to maintain system responsiveness.

ISR Characteristics

- Fast Execution: Must complete quickly to avoid blocking other interrupts

- Atomic Operations: Cannot be interrupted by lower-priority interrupts

- Minimal Stack Usage: Limited stack space available during interrupt context

- No Blocking Calls: Cannot perform operations that might cause the handler to sleep

Sample ISR Implementation

Here’s a simplified example of a keyboard interrupt handler in C:

// Keyboard ISR example

void keyboard_interrupt_handler() {

// Save processor state (done automatically by hardware)

// Read the scancode from keyboard port

unsigned char scancode = inb(KEYBOARD_DATA_PORT);

// Process the scancode

if (scancode < 128) {

// Key pressed

process_key_press(scancode);

} else {

// Key released

process_key_release(scancode - 128);

}

// Send End of Interrupt signal to PIC

outb(PIC1_COMMAND, EOI);

// Return from interrupt (restores processor state automatically)

}

Interrupt Handling Process

The interrupt handling process follows a well-defined sequence to ensure system stability and proper resource management.

Step-by-Step Process

- Interrupt Detection: Hardware device raises an interrupt signal

- Interrupt Controller: Routes the interrupt to the appropriate CPU

- Context Saving: CPU automatically saves current instruction pointer and flags

- Interrupt Disable: Prevents nested interrupts during critical handling

- Vector Lookup: CPU uses Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT) to find ISR address

- ISR Execution: Transfer control to the appropriate interrupt handler

- Interrupt Acknowledgment: Signal to hardware that interrupt is being processed

- Handler Logic: Execute device-specific handling code

- Context Restoration: Restore all saved registers and flags

- Return: Resume execution of interrupted program

Interrupt Priority and Nesting

Modern systems implement interrupt priority schemes to ensure that critical interrupts can preempt less important ones. This hierarchical approach prevents low-priority interrupts from blocking time-critical operations.

Priority Levels Example

| Priority Level | Interrupt Type | Example | Can Be Preempted By |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Highest) | Non-Maskable | Memory errors, power failure | None |

| 1 | System Timer | Clock tick, scheduling | NMI only |

| 2 | Critical I/O | Disk controller, network | NMI, Timer |

| 3 (Lowest) | User Input | Keyboard, mouse | All higher priorities |

Practical Examples and Code Implementation

Timer Interrupt Handler

The system timer interrupt is crucial for task scheduling and timekeeping:

volatile unsigned long system_ticks = 0;

void timer_interrupt_handler() {

// Increment system tick counter

system_ticks++;

// Update system time

update_system_time();

// Trigger process scheduler every 10ms

if (system_ticks % 10 == 0) {

schedule_next_process();

}

// Send EOI to interrupt controller

outb(PIC1_COMMAND, EOI);

}

Network Interrupt Handler

Network card interrupts handle incoming packet notifications:

void network_interrupt_handler() {

// Read network card status

uint16_t status = read_network_status();

if (status & RX_PACKET_READY) {

// Packet received - add to receive queue

packet_t *packet = read_network_packet();

enqueue_received_packet(packet);

// Wake up network processing thread

wakeup_network_thread();

}

if (status & TX_COMPLETE) {

// Transmission complete - free buffer

free_transmit_buffer();

}

// Clear interrupt flags

clear_network_interrupt();

outb(PIC1_COMMAND, EOI);

}

Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT)

The Interrupt Descriptor Table is a data structure used by x86 processors to determine the correct response to interrupts and exceptions. Each entry in the IDT contains information about how to handle a specific interrupt.

IDT Entry Structure

| Field | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Offset Low | 16 bits | Lower 16 bits of ISR address |

| Selector | 16 bits | Code segment selector |

| Reserved | 8 bits | Must be zero |

| Type & Attributes | 8 bits | Gate type and privilege level |

| Offset High | 16 bits | Upper 16 bits of ISR address |

Performance Considerations

Efficient interrupt handling is crucial for system performance. Poor interrupt handling can lead to system responsiveness issues and potential data loss.

Optimization Strategies

- Minimize ISR Duration: Keep interrupt handlers as short as possible

- Deferred Processing: Use bottom halves or tasklets for complex operations

- Interrupt Coalescing: Batch multiple interrupts to reduce overhead

- NAPI (New API): Polling mode for high-frequency interrupts

- Interrupt Affinity: Bind interrupts to specific CPU cores

Top Half vs Bottom Half

Modern operating systems split interrupt processing into two parts:

| Aspect | Top Half (ISR) | Bottom Half (Deferred) |

|---|---|---|

| Execution Context | Interrupt context | Process context |

| Duration | Very short (microseconds) | Longer (milliseconds) |

| Operations | Critical, time-sensitive | Complex processing |

| Interrupts | Disabled | Enabled |

| Example | Acknowledge hardware | Process network packets |

Common Issues and Debugging

Interrupt Storm

An interrupt storm occurs when a device generates interrupts faster than the system can handle them, potentially causing system lockup.

// Example: Interrupt rate limiting

static unsigned long last_interrupt_time = 0;

static int interrupt_count = 0;

void rate_limited_isr() {

unsigned long current_time = get_system_time();

// Reset counter every second

if (current_time - last_interrupt_time > 1000) {

interrupt_count = 0;

last_interrupt_time = current_time;

}

interrupt_count++;

// Disable interrupt if rate too high

if (interrupt_count > MAX_INTERRUPTS_PER_SECOND) {

disable_device_interrupt();

schedule_delayed_re_enable();

return;

}

// Normal interrupt processing

handle_device_interrupt();

}

Lost Interrupts

Interrupts can be lost due to:

- Interrupt Masking: Interrupts disabled for too long

- Hardware Buffer Overflow: Device buffers full

- Slow ISR Processing: Handler takes too long to complete

- Priority Inversion: High-priority interrupts blocked by low-priority handlers

Best Practices for Interrupt Handling

Design Guidelines

- Keep ISRs Short: Minimize time spent in interrupt context

- Avoid Blocking Operations: No sleep, mutex, or I/O operations in ISRs

- Use Proper Synchronization: Employ spinlocks and atomic operations

- Handle Errors Gracefully: Implement robust error handling

- Document Interrupt Behavior: Clear documentation for maintainability

Sample Best Practice Implementation

// Good ISR implementation example

void optimized_network_isr() {

// Quick acknowledgment

uint32_t status = read_and_clear_interrupt_status();

// Minimal processing in ISR

if (status & RX_INTERRUPT) {

// Just set flag and schedule bottom half

set_rx_flag();

schedule_rx_tasklet();

}

if (status & TX_INTERRUPT) {

set_tx_flag();

schedule_tx_tasklet();

}

// Quick EOI

send_eoi();

}

// Bottom half processing

void network_rx_tasklet() {

// Complex processing in process context

while (packets_available()) {

packet_t *pkt = get_next_packet();

process_network_packet(pkt);

}

}

Modern Interrupt Handling Mechanisms

Message Signaled Interrupts (MSI)

MSI is a modern alternative to traditional pin-based interrupts, offering better performance and scalability:

- No Shared Interrupt Lines: Each device gets unique interrupt vector

- Better Performance: Reduced interrupt latency

- Scalability: Supports more devices without IRQ conflicts

- Memory-Based: Uses memory writes instead of electrical signals

IOMMU and Interrupt Remapping

Modern systems use IOMMU (Input-Output Memory Management Unit) for interrupt security and virtualization support:

- Interrupt Isolation: Prevents malicious devices from triggering arbitrary interrupts

- Virtual Machine Support: Enables interrupt forwarding to guest VMs

- Interrupt Translation: Maps physical interrupts to virtual interrupt vectors

Conclusion

Interrupt handling is a cornerstone of modern operating system design, enabling efficient hardware-software communication and system responsiveness. Understanding the intricacies of hardware interrupts, ISR implementation, and performance optimization is essential for system programmers and kernel developers.

Key takeaways for effective interrupt handling include keeping ISRs minimal and fast, using deferred processing for complex operations, implementing proper synchronization mechanisms, and following established best practices for robust system design.

As hardware continues to evolve with technologies like MSI, IOMMU, and multi-core architectures, interrupt handling mechanisms will continue to adapt, but the fundamental principles of efficient, reliable interrupt processing remain constant.

- Introduction to Interrupt Handling

- What are Interrupts?

- Hardware Interrupts: The Foundation

- Interrupt Service Routines (ISR)

- Interrupt Handling Process

- Interrupt Priority and Nesting

- Practical Examples and Code Implementation

- Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT)

- Performance Considerations

- Common Issues and Debugging

- Best Practices for Interrupt Handling

- Modern Interrupt Handling Mechanisms

- Conclusion