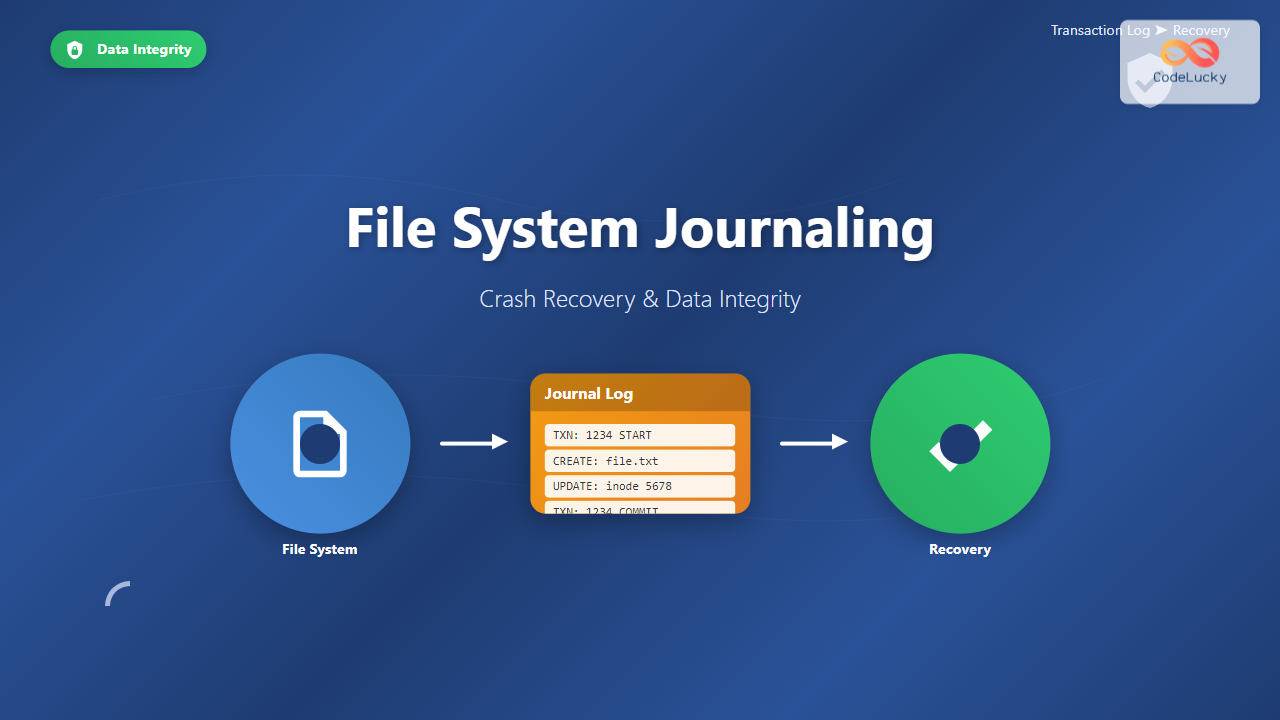

Understanding File System Journaling

File system journaling is a critical mechanism that ensures data integrity and enables rapid crash recovery in modern operating systems. When your computer suddenly loses power or crashes during a file operation, journaling prevents data corruption by maintaining a detailed log of all file system changes before they’re actually applied to disk.

Think of journaling as a transaction log for your file system – similar to how databases maintain transaction logs to ensure ACID properties. Before any metadata changes occur on disk, the file system first writes these changes to a special area called the journal or log.

Types of Journaling

File systems implement different levels of journaling based on performance requirements and data protection needs:

Metadata-Only Journaling

Metadata journaling logs only file system structural information such as directory entries, inode updates, and allocation bitmaps. This approach provides faster performance since actual file data isn’t journaled, but offers limited protection against data corruption.

// Example: ext4 metadata journaling

mount /dev/sda1 /mnt/data -o data=ordered

Full Data Journaling

Full journaling logs both metadata and actual file content changes. While this provides maximum data protection, it significantly impacts performance due to the overhead of writing data twice – once to the journal and once to the final location.

// Example: ext4 full journaling

mount /dev/sda1 /mnt/data -o data=journal

Ordered Journaling

Ordered journaling represents a compromise between performance and safety. Metadata changes are journaled, but data writes are ordered to occur before the corresponding metadata changes are committed to the journal.

// Example: ext4 ordered mode (default)

mount /dev/sda1 /mnt/data -o data=ordered

Journal Structure and Implementation

A typical journal consists of several key components that work together to ensure transaction atomicity:

Journal Superblock

The journal superblock contains essential information about the journal layout, including:

- Journal size and block size

- Sequence numbers for transaction tracking

- Head and tail pointers for circular buffer management

- Feature flags and compatibility information

// Examining ext4 journal superblock

tune2fs -l /dev/sda1 | grep -i journal

# Output example:

# Filesystem features: has_journal ext_attr resize_inode dir_index

# Journal size: 128M

# Journal length: 32768

# Journal sequence: 0x0000001a

Transaction Management

Each transaction in the journal follows a strict protocol:

- Transaction Start: Allocate transaction ID and journal space

- Write Phase: Log all changes to descriptor and data blocks

- Commit Phase: Write commit block to make transaction durable

- Checkpoint Phase: Apply changes to main file system

- Cleanup Phase: Mark journal space as reusable

Crash Recovery Process

When a system recovers from an unexpected shutdown, the file system performs a systematic recovery process:

Recovery Example with ext4

Let’s examine how ext4 handles recovery after a system crash:

# Force an ext4 file system check

fsck.ext4 -f /dev/sda1

# Output during recovery:

# e2fsck 1.46.2 (28-Feb-2021)

# Pass 1: Checking inodes, blocks, and sizes

# Pass 2: Checking directory structure

# Pass 3: Checking directory connectivity

# Pass 4: Checking reference counts

# Pass 5: Checking group summary information

# /dev/sda1: recovering journal

# /dev/sda1: clean, 45123/655360 files, 234567/2621440 blocks

Journal Replay Process

During recovery, the file system kernel module performs these steps:

// Kernel log messages during ext4 recovery

dmesg | grep -i "ext4\|journal"

# Example output:

# [ 2.456] EXT4-fs (sda1): mounted filesystem with ordered data mode

# [ 2.458] JBD2: recovery started, transaction 1234

# [ 2.462] JBD2: replaying transaction 1234

# [ 2.465] JBD2: recovery complete, 15 transactions replayed

# [ 2.467] EXT4-fs (sda1): recovery complete

Performance Considerations

Journaling introduces performance overhead that varies based on the journaling mode and workload characteristics:

Write Amplification

Write amplification occurs because data must be written multiple times – first to the journal, then to the final location. This is particularly noticeable in full journaling mode:

# Benchmark different journaling modes

# Metadata journaling

echo 3 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches

time dd if=/dev/zero of=/mnt/test_meta bs=1M count=1000 oflag=sync

# Full journaling

mount -o remount,data=journal /mnt/data

echo 3 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches

time dd if=/dev/zero of=/mnt/test_full bs=1M count=1000 oflag=sync

Journal Size Optimization

Journal size directly impacts both performance and recovery time. Larger journals can buffer more transactions but require more recovery time:

# Create ext4 with custom journal size

mkfs.ext4 -J size=256 /dev/sda1 # 256MB journal

# Tune existing journal size

tune2fs -J size=128 /dev/sda1 # Resize to 128MB

File System Implementations

ext4 Journaling

ext4 uses the JBD2 (Journaling Block Device v2) layer for transaction management:

# View current ext4 journal settings

tune2fs -l /dev/sda1 | grep -E "(journal|Journal)"

# Configure journal options

tune2fs -O ^has_journal /dev/sda1 # Disable journaling

tune2fs -O has_journal /dev/sda1 # Enable journaling

tune2fs -J device=/dev/sdb1 /dev/sda1 # External journal

XFS Journaling

XFS implements metadata-only journaling with excellent performance characteristics:

# XFS journal information

xfs_info /mnt/xfs_mount

# Output example:

# meta-data=/dev/sda1 isize=512 agcount=4, agsize=65536 blks

# data = bsize=4096 blocks=262144, imaxpct=25

# naming =version 2 bsize=4096 ascii-ci=0 ftype=1

# log =internal bsize=4096 blocks=2560, version=2

NTFS Journaling

NTFS uses a transaction log file ($LogFile) for metadata journaling:

# Windows: View NTFS journal information

fsutil usn queryjournal C:

# Linux: Mount NTFS with journal recovery

mount -t ntfs-3g /dev/sda1 /mnt/ntfs -o recover

Advanced Journaling Concepts

Barrier Operations

Write barriers ensure proper ordering of journal writes to maintain transaction integrity:

# Check if barriers are enabled

cat /proc/mounts | grep barrier

# Mount with barriers disabled (not recommended)

mount -o nobarrier /dev/sda1 /mnt/data

# Enable barriers for safety

mount -o barrier /dev/sda1 /mnt/data

External Journaling

Some file systems support external journaling where the journal resides on a separate, faster device:

# Create external journal device

mke2fs -O journal_dev /dev/nvme0n1p1

# Create ext4 with external journal

mkfs.ext4 -J device=/dev/nvme0n1p1 /dev/sda1

# Benefits: Journal on SSD, data on HDD

# - Faster journal writes

# - Reduced seek times

# - Better performance isolation

Monitoring and Troubleshooting

Journal Health Monitoring

Regular monitoring helps identify potential journaling issues before they cause problems:

# Check file system and journal health

fsck.ext4 -n /dev/sda1 # Read-only check

# Monitor journal statistics

cat /proc/fs/jbd2/sda1-8/info

# Example output:

# 1234 transactions (5678 requested), each up to 8192 blocks

# average: 234ms waiting for transaction

# 456ms running transaction

# 789ms transaction was being locked

# 123ms flushing data (in ordered mode)

# 456ms logging transaction

# 789ms average transaction commit time

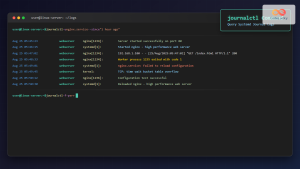

Common Journal Issues

Understanding common journaling problems helps in quick diagnosis:

# Journal corruption symptoms

dmesg | grep -E "(journal|jbd|ext4)" | tail -20

# Common error messages:

# "JBD2: Journal checksum error"

# "EXT4-fs error: Journal transaction X is corrupt"

# "JBD2: IO error reading journal superblock"

# Recovery actions:

# 1. Backup important data

# 2. Run file system check

# 3. Consider journal recreation if corruption persists

Performance Tuning

Optimizing journaling performance requires balancing safety with speed:

# Tune journal commit interval

echo 10 > /proc/sys/fs/jbd2/sda1-8/max_transaction_age

# Configure write-back caching

hdparm -W1 /dev/sda1 # Enable write caching

# Adjust dirty page parameters

echo 15 > /proc/sys/vm/dirty_background_ratio

echo 30 > /proc/sys/vm/dirty_ratio

# Monitor impact

iostat -x 1 10 # Watch I/O patterns

Best Practices

Follow these guidelines for optimal journaling configuration:

- Choose appropriate journaling mode based on workload requirements

- Size journals appropriately – typically 64-128MB for most workloads

- Enable barriers unless using battery-backed RAID controllers

- Regular monitoring of journal health and performance metrics

- Backup strategies that account for journal replay during recovery

File system journaling represents a fundamental advancement in storage reliability, providing the foundation for robust, crash-resistant computing systems. Understanding its implementation and proper configuration ensures optimal balance between performance and data protection in modern operating environments.