The file command is one of the most powerful and underutilized utilities in Linux for determining file types and analyzing their contents. Unlike relying on file extensions, the file command examines the actual content and structure of files to provide accurate type identification. This comprehensive guide explores advanced usage patterns, options, and practical applications that will elevate your system administration skills.

Understanding the file Command Fundamentals

The file command works by examining file headers, magic numbers, and content patterns stored in a database called the “magic file.” This approach provides reliable file type detection regardless of filename extensions, making it invaluable for security analysis, data recovery, and system maintenance.

Basic Syntax and Core Functionality

file [options] filename(s)Let’s start with basic examples to understand the output format:

$ file document.txt

document.txt: UTF-8 Unicode text

$ file image.jpg

image.jpg: JPEG image data, JFIF standard 1.01, aspect ratio, density 1x1, segment length 16, baseline, precision 8, 3840x2160, frames 3

$ file script.sh

script.sh: Bourne-Again shell script, ASCII text executableAdvanced Options for Detailed Analysis

Verbose Output with -v Flag

The verbose option provides detailed information about the file command’s version and configuration:

$ file -v

file-5.39

magic file from /etc/magic:/usr/share/misc/magic

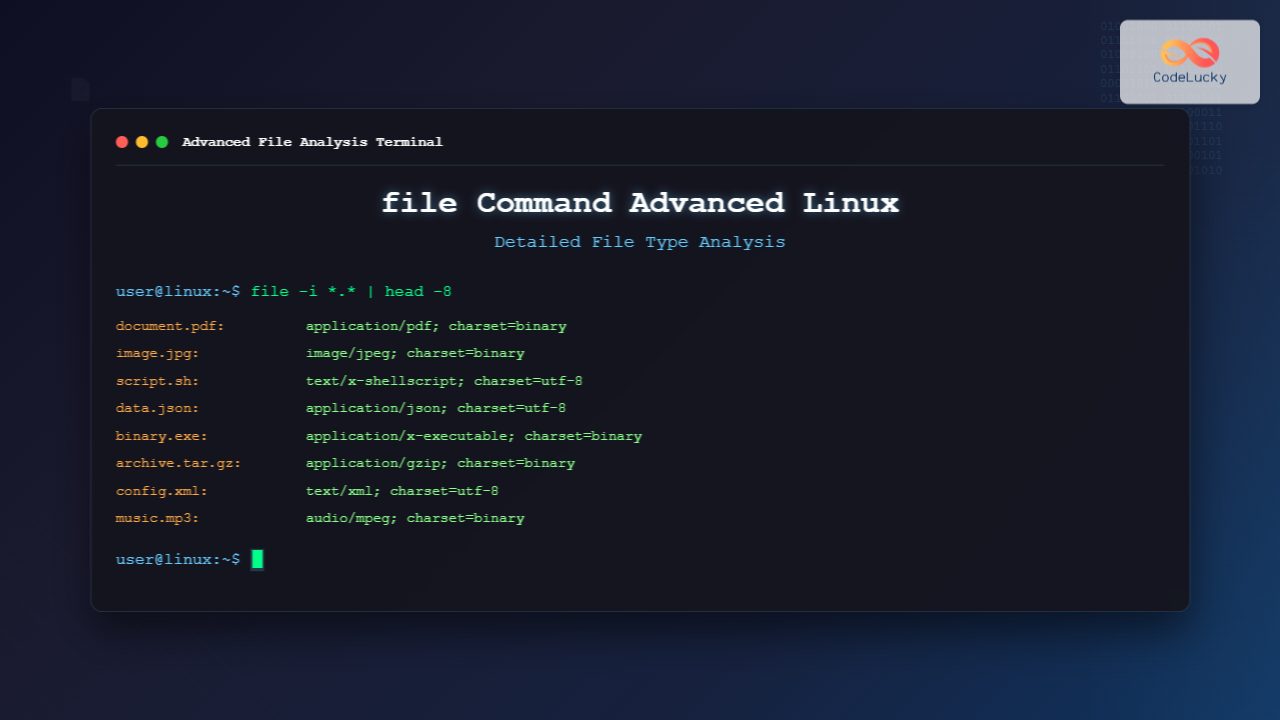

seccomp support includedMIME Type Detection with -i Flag

For web development and application integration, MIME type detection is crucial:

$ file -i document.pdf

document.pdf: application/pdf; charset=binary

$ file -i audio.mp3

audio.mp3: audio/mpeg; charset=binary

$ file -i webpage.html

webpage.html: text/html; charset=utf-8Brief Output with -b Flag

The brief flag removes the filename from output, useful for scripting:

$ file -b image.png

PNG image data, 1920 x 1080, 8-bit/color RGBA, non-interlaced

$ file -bi config.json

application/json; charset=utf-8Analyzing Special File Types

Executable and Binary Analysis

The file command excels at analyzing executable files and providing architectural information:

$ file /bin/ls

/bin/ls: ELF 64-bit LSB shared object, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=4f3d1d0f2a6c5e7b8c9d0e1f2a3b4c5d6e7f8g9h, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, stripped

$ file program.exe

program.exe: PE32+ executable (console) x86-64, for MS WindowsArchive and Compressed File Detection

$ file backup.tar.gz

backup.tar.gz: gzip compressed data, from Unix, original size modulo 2^32 10485760

$ file data.zip

data.zip: Zip archive data, at least v2.0 to extract

$ file package.deb

package.deb: Debian binary package (format 2.0)Advanced Techniques and Options

Following Symbolic Links with -L Flag

By default, file analyzes symbolic links themselves. Use -L to follow links:

$ file link.txt

link.txt: symbolic link to /home/user/original.txt

$ file -L link.txt

link.txt: ASCII textRecursive Directory Analysis with -r Flag

Analyze entire directory structures recursively:

$ file -r project_directory/

project_directory/src/main.c: C source, ASCII text

project_directory/bin/app: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64

project_directory/docs/README.md: UTF-8 Unicode text

project_directory/config.json: JSON dataCustom Magic Files with -m Flag

Specify custom magic files for specialized detection:

$ file -m /usr/local/share/custom-magic datafile.custom

datafile.custom: Custom Application Data Format v2.1Practical System Administration Applications

Security and Malware Detection

Use file command for security analysis and detecting potentially malicious files:

$ file suspicious_file

suspicious_file: PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386, for MS Windows

$ file -i unknown_binary

unknown_binary: application/x-executable; charset=binaryData Recovery and Forensics

When file extensions are missing or corrupted, the file command helps identify content:

$ file recovered_data_*

recovered_data_001: JPEG image data, EXIF standard

recovered_data_002: Microsoft Word 2007+

recovered_data_003: SQLite 3.x databaseBatch File Analysis Scripts

Create powerful scripts for automated file analysis:

#!/bin/bash

# Analyze all files in directory and categorize by type

for file in *; do

if [ -f "$file" ]; then

filetype=$(file -b "$file")

echo "$file: $filetype"

fi

done | sort -k2Performance Optimization and Best Practices

Efficient Large-Scale Analysis

When analyzing thousands of files, optimize performance with these approaches:

# Process multiple files in single command

$ file *.txt *.doc *.pdf

# Use null separator for script processing

$ find /path -type f -print0 | xargs -0 file -bError Handling and Edge Cases

Handle special cases and errors gracefully:

$ file /dev/null

/dev/null: character special (1/3)

$ file non_existent_file

non_existent_file: cannot open `non_existent_file' (No such file or directory)

$ file /proc/cpuinfo

/proc/cpuinfo: ASCII textIntegration with Other Linux Commands

Combining with find and grep

Create powerful file analysis pipelines:

# Find all executable files

$ find /usr/bin -type f -exec file {} \; | grep "executable"

# Identify all image files recursively

$ find . -type f -exec file -i {} \; | grep "image/"

# Count files by type

$ file * | cut -d: -f2 | sort | uniq -cAutomated File Classification

#!/bin/bash

# Classify files into directories by type

for file in *; do

if [ -f "$file" ]; then

mimetype=$(file -bi "$file" | cut -d';' -f1)

case $mimetype in

"image/"*) mkdir -p images && mv "$file" images/ ;;

"text/"*) mkdir -p documents && mv "$file" documents/ ;;

"application/pdf") mkdir -p pdfs && mv "$file" pdfs/ ;;

esac

fi

doneTroubleshooting and Common Issues

Dealing with Unrecognized File Types

When file returns “data” or generic descriptions, try these approaches:

$ file mysterious_file

mysterious_file: data

# Try with different options

$ file -k mysterious_file # Continue after first match

$ file -e ascii mysterious_file # Exclude ASCII text detectionMagic File Database Issues

Verify and update magic file databases:

# Check magic file location

$ file --help | grep magic

# Compile custom magic files

$ file -C -m custom.magicAdvanced Scripting Examples

File Type Statistics Generator

#!/bin/bash

# Generate file type statistics for a directory

echo "File Type Analysis Report"

echo "========================="

file -i $(find . -type f) | \

awk -F': ' '{print $2}' | \

cut -d';' -f1 | \

sort | uniq -c | \

sort -nr | \

head -10Security Audit Script

#!/bin/bash

# Identify potentially suspicious files

echo "Security Audit: Executable Files Analysis"

find /tmp /var/tmp -type f -executable -exec file {} \; | \

grep -E "(executable|script)" | \

while IFS=': ' read -r filename filetype; do

echo "ALERT: $filename - $filetype"

ls -la "$filename"

donePerformance Monitoring and Optimization

Monitor file command performance for large-scale operations:

# Time file analysis operations

$ time file /usr/bin/*

# Profile memory usage

$ /usr/bin/time -v file large_file.binConclusion

The file command is an indispensable tool for Linux system administrators and developers. Its ability to accurately identify file types regardless of extensions makes it crucial for security analysis, data recovery, and automated file processing. By mastering the advanced options and techniques covered in this guide, you’ll be able to leverage the full power of file type analysis in your daily Linux operations.

Whether you’re conducting security audits, recovering corrupted data, or building automated file processing systems, the file command provides the foundation for reliable file type detection and analysis. Practice these examples and incorporate them into your system administration toolkit for more efficient and secure Linux environments.

- Understanding the file Command Fundamentals

- Advanced Options for Detailed Analysis

- Analyzing Special File Types

- Advanced Techniques and Options

- Practical System Administration Applications

- Performance Optimization and Best Practices

- Integration with Other Linux Commands

- Troubleshooting and Common Issues

- Advanced Scripting Examples

- Performance Monitoring and Optimization

- Conclusion