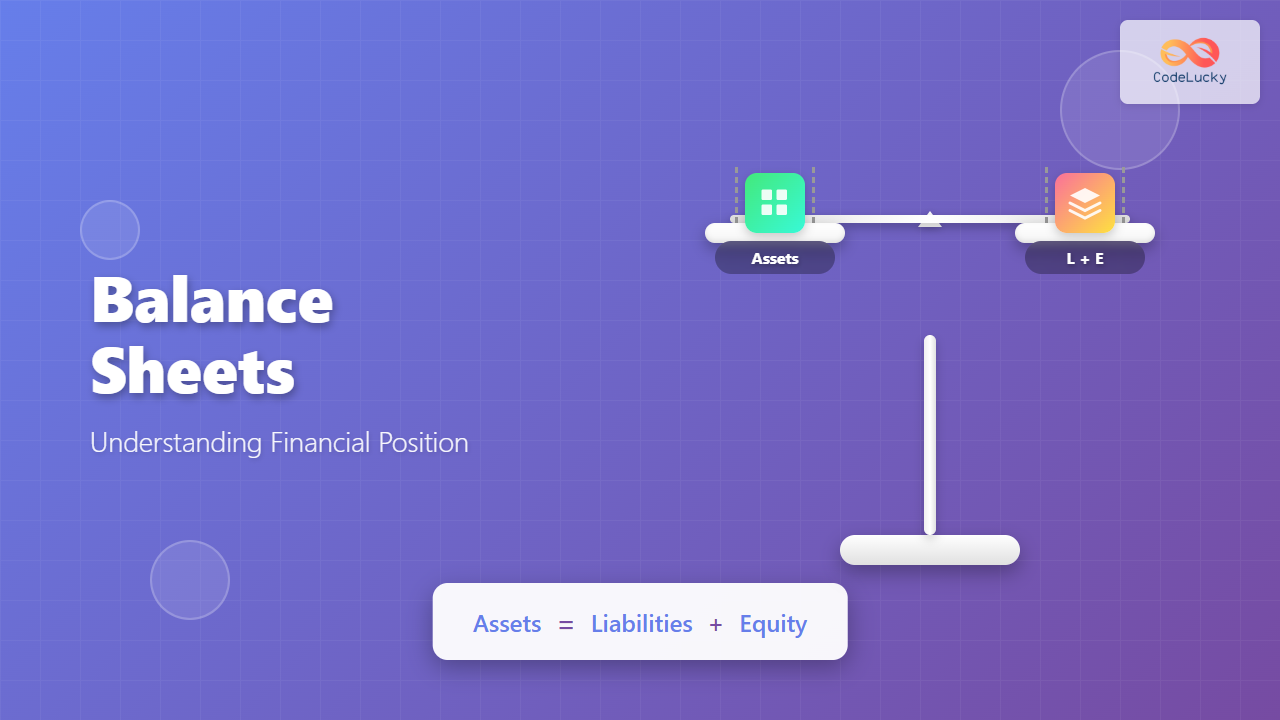

A balance sheet is one of the three fundamental financial statements that provide a snapshot of a company’s financial position at a specific point in time. Unlike the income statement that shows performance over a period, the balance sheet captures what a company owns, what it owes, and the residual value belonging to shareholders at a single moment.

Understanding balance sheets is essential for investors, business owners, creditors, and anyone involved in financial decision-making. This comprehensive guide will walk you through every aspect of balance sheets, from basic concepts to advanced analysis techniques.

What is a Balance Sheet?

A balance sheet is a financial statement that reports a company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity at a specific date. The statement follows the fundamental accounting equation:

\[ \text{Assets} = \text{Liabilities} + \text{Shareholders’ Equity} \]

This equation must always balance, which is why the statement is called a “balance sheet.” Every transaction affects at least two accounts, maintaining this equilibrium. The balance sheet provides crucial information about a company’s liquidity, solvency, and capital structure.

The Three Main Components

Assets: What the Company Owns

Assets represent everything of value that a company owns or controls. They are resources expected to provide future economic benefits. Assets are typically listed in order of liquidity—how quickly they can be converted to cash.

Current Assets

Current assets are expected to be converted to cash or used within one year or one operating cycle, whichever is longer. These include:

- Cash and cash equivalents: The most liquid assets including currency, bank deposits, and short-term investments

- Accounts receivable: Money owed by customers for goods or services delivered on credit

- Inventory: Raw materials, work-in-progress, and finished goods ready for sale

- Prepaid expenses: Payments made in advance for future benefits like insurance or rent

- Marketable securities: Short-term investments that can be quickly sold

Non-Current Assets

Non-current assets, also called fixed or long-term assets, provide value over multiple years. Key categories include:

- Property, plant, and equipment (PP&E): Land, buildings, machinery, vehicles, and equipment

- Intangible assets: Patents, trademarks, copyrights, goodwill, and brand value

- Long-term investments: Stocks, bonds, or real estate held for extended periods

- Deferred tax assets: Future tax benefits from past losses or timing differences

Liabilities: What the Company Owes

Liabilities represent a company’s financial obligations—debts and other amounts owed to creditors, suppliers, employees, and governments. Like assets, liabilities are classified based on when they must be paid.

Current Liabilities

Current liabilities are obligations due within one year or one operating cycle. Common examples include:

- Accounts payable: Money owed to suppliers for goods or services purchased on credit

- Short-term debt: Loans and credit lines due within a year

- Accrued expenses: Obligations for expenses incurred but not yet paid, like wages or utilities

- Unearned revenue: Advance payments received for products or services not yet delivered

- Current portion of long-term debt: The part of long-term loans due within the next year

Non-Current Liabilities

Non-current liabilities are long-term obligations extending beyond one year:

- Long-term debt: Bonds, mortgages, and loans with maturity beyond one year

- Deferred tax liabilities: Taxes owed in future periods due to timing differences

- Pension obligations: Future retirement benefits promised to employees

- Lease obligations: Long-term lease commitments for equipment or property

Shareholders’ Equity: The Owners’ Stake

Shareholders’ equity represents the residual interest in assets after deducting liabilities. It’s essentially what would belong to shareholders if all assets were liquidated and all debts paid. The main components include:

- Share capital: Money received from issuing common and preferred stock

- Retained earnings: Cumulative profits kept in the business rather than distributed as dividends

- Additional paid-in capital: Amount paid by investors above the par value of shares

- Treasury stock: Company’s own shares bought back from shareholders (shown as a reduction)

- Accumulated other comprehensive income: Gains and losses not included in net income

Balance Sheet Formats

Balance sheets can be presented in two primary formats, each offering the same information but arranged differently for clarity and emphasis.

Account Format (Horizontal)

The account format displays assets on the left side and liabilities plus equity on the right side, resembling a traditional T-account structure. This format emphasizes the accounting equation’s balance:

Assets = Liabilities + EquityReport Format (Vertical)

The report format lists assets first, followed by liabilities, and then shareholders’ equity in a vertical arrangement. This format is more common in modern financial reporting because it’s easier to read and compare across periods:

Assets

- Current Assets

- Non-Current Assets

Total Assets

Liabilities

- Current Liabilities

- Non-Current Liabilities

Shareholders' Equity

Total Liabilities and EquityReal-World Example: TechStart Inc.

Let’s examine a detailed balance sheet for a fictional technology company to understand how the components work together. TechStart Inc. is a software development company with \$5 million in annual revenue.

TechStart Inc. Balance Sheet (December 31, 2024)

| Account | Amount ($) |

|---|---|

| ASSETS | |

| Current Assets | |

| Cash and Cash Equivalents | 450,000 |

| Accounts Receivable | 320,000 |

| Prepaid Expenses | 30,000 |

| Total Current Assets | 800,000 |

| Non-Current Assets | |

| Property and Equipment | 250,000 |

| Less: Accumulated Depreciation | (50,000) |

| Intangible Assets (Software) | 150,000 |

| Total Non-Current Assets | 350,000 |

| TOTAL ASSETS | 1,150,000 |

| LIABILITIES | |

| Current Liabilities | |

| Accounts Payable | 180,000 |

| Accrued Expenses | 95,000 |

| Unearned Revenue | 50,000 |

| Current Portion of Long-Term Debt | 75,000 |

| Total Current Liabilities | 400,000 |

| Non-Current Liabilities | |

| Long-Term Debt | 200,000 |

| Total Non-Current Liabilities | 200,000 |

| TOTAL LIABILITIES | 600,000 |

| SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY | |

| Common Stock | 300,000 |

| Retained Earnings | 250,000 |

| TOTAL SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY | 550,000 |

| TOTAL LIABILITIES AND EQUITY | 1,150,000 |

Notice how the total assets (\$1,150,000) perfectly equal the sum of total liabilities (\$600,000) and shareholders’ equity (\$550,000). This demonstrates the fundamental accounting equation in action.

Key Financial Ratios from Balance Sheets

Balance sheets provide the foundation for calculating important financial ratios that help evaluate a company’s financial health. These ratios offer insights into liquidity, leverage, efficiency, and overall stability.

Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios measure a company’s ability to meet short-term obligations using current assets.

Current Ratio

The current ratio compares current assets to current liabilities:

\[ \text{Current Ratio} = \frac{\text{Current Assets}}{\text{Current Liabilities}} \]

For TechStart Inc.:

\[ \text{Current Ratio} = \frac{800,000}{400,000} = 2.0 \]

A ratio above 1.0 indicates the company can cover its short-term obligations. TechStart’s ratio of 2.0 suggests strong short-term financial health, with $2 of current assets for every $1 of current liabilities.

Quick Ratio (Acid-Test Ratio)

The quick ratio excludes inventory and other less liquid current assets:

\[ \text{Quick Ratio} = \frac{\text{Current Assets} – \text{Inventory}}{\text{Current Liabilities}} \]

Since TechStart is a service company with no inventory:

\[ \text{Quick Ratio} = \frac{800,000}{400,000} = 2.0 \]

Leverage Ratios

Leverage ratios assess how much a company relies on debt versus equity financing.

Debt-to-Equity Ratio

This ratio compares total liabilities to shareholders’ equity:

\[ \text{Debt-to-Equity Ratio} = \frac{\text{Total Liabilities}}{\text{Shareholders’ Equity}} \]

For TechStart Inc.:

\[ \text{Debt-to-Equity Ratio} = \frac{600,000}{550,000} = 1.09 \]

A ratio of 1.09 means TechStart has $1.09 of debt for every $1 of equity. This moderate leverage indicates a balanced capital structure, neither overly conservative nor excessively risky.

Debt Ratio

The debt ratio shows the percentage of assets financed by debt:

\[ \text{Debt Ratio} = \frac{\text{Total Liabilities}}{\text{Total Assets}} \]

For TechStart Inc.:

\[ \text{Debt Ratio} = \frac{600,000}{1,150,000} = 0.52 \text{ or } 52\% \]

Efficiency Ratios

While some efficiency ratios require income statement data, the asset turnover ratio uses balance sheet information to measure how effectively a company uses its assets to generate revenue.

Working Capital Management

Working capital represents the difference between current assets and current liabilities. It measures the short-term financial health and operational efficiency of a business.

\[ \text{Working Capital} = \text{Current Assets} – \text{Current Liabilities} \]

For TechStart Inc.:

\[ \text{Working Capital} = 800,000 – 400,000 = \$400,000 \]

Positive working capital of \$400,000 indicates TechStart has sufficient short-term assets to cover short-term obligations. This cushion allows the company to handle unexpected expenses, invest in growth opportunities, and maintain smooth operations.

Working Capital Cycle

The working capital cycle (also called the cash conversion cycle) measures how long it takes a company to convert investments in inventory and receivables back into cash. Understanding this cycle helps optimize cash flow:

Common Balance Sheet Adjustments

Balance sheets require various adjustments to accurately reflect a company’s financial position. Understanding these adjustments is crucial for proper financial reporting and analysis.

Depreciation and Amortization

Tangible assets like equipment depreciate over time, while intangible assets like patents amortize. These non-cash expenses reduce asset values and are accumulated in contra-asset accounts:

- Accumulated depreciation reduces property, plant, and equipment values

- Accumulated amortization reduces intangible asset values

- Both reflect the portion of asset cost already expensed

In TechStart’s balance sheet, equipment originally worth \$250,000 has accumulated depreciation of \$50,000, showing a net book value of \$200,000.

Allowance for Doubtful Accounts

Not all accounts receivable will be collected. Companies estimate uncollectible amounts and create an allowance, reducing receivables to their net realizable value:

\[ \text{Net Accounts Receivable} = \text{Gross Receivables} – \text{Allowance for Doubtful Accounts} \]

Inventory Valuation Methods

Companies use different methods to value inventory, which can significantly impact the balance sheet:

- First-In, First-Out (FIFO): Assumes oldest inventory sells first

- Last-In, First-Out (LIFO): Assumes newest inventory sells first

- Weighted Average Cost: Uses average cost of all units

- Specific Identification: Tracks actual cost of each item

Balance Sheet Analysis Techniques

Effective balance sheet analysis goes beyond simply reading numbers. It involves comparing data across time periods, against industry benchmarks, and understanding the relationships between components.

Horizontal Analysis (Trend Analysis)

Horizontal analysis compares balance sheet items across multiple periods to identify trends, growth patterns, and potential concerns. Calculate the change in dollar amounts and percentages:

\[ \text{Change \%} = \frac{\text{Current Year} – \text{Prior Year}}{\text{Prior Year}} \times 100 \]

Vertical Analysis (Common-Size Statements)

Vertical analysis expresses each balance sheet item as a percentage of total assets. This standardization allows meaningful comparisons between companies of different sizes:

\[ \text{Item \%} = \frac{\text{Line Item}}{\text{Total Assets}} \times 100 \]

TechStart Inc. Common-Size Balance Sheet

| Account | Amount ($) | % of Total Assets |

|---|---|---|

| Current Assets | 800,000 | 69.6% |

| Non-Current Assets | 350,000 | 30.4% |

| Total Assets | 1,150,000 | 100.0% |

| Current Liabilities | 400,000 | 34.8% |

| Non-Current Liabilities | 200,000 | 17.4% |

| Shareholders’ Equity | 550,000 | 47.8% |

| Total Liabilities and Equity | 1,150,000 | 100.0% |

This analysis reveals TechStart maintains a liquid asset base (69.6% current assets), moderate leverage (52.2% liabilities), and substantial equity cushion (47.8%).

Industry Variations in Balance Sheets

Balance sheet structure varies significantly across industries based on business models, capital requirements, and operational characteristics.

Manufacturing Companies

Manufacturing firms typically show:

- High inventory levels across raw materials, work-in-progress, and finished goods

- Substantial property, plant, and equipment investments

- Significant accounts payable to suppliers

- Lower cash balances due to capital-intensive operations

Retail Companies

Retail businesses generally have:

- Large finished goods inventory representing merchandise for sale

- Moderate fixed assets primarily in store locations and distribution centers

- Low accounts receivable if cash-based sales dominate

- Seasonal fluctuations in working capital

Service Companies

Service-based businesses often display:

Technology Companies

Tech firms frequently show:

- High cash reserves from strong cash flow generation

- Substantial intangible assets including software and patents

- Deferred revenue from subscription-based business models

- Stock-based compensation reflected in equity

Red Flags in Balance Sheet Analysis

Experienced analysts watch for warning signs that may indicate financial distress, aggressive accounting, or operational problems.

Liquidity Concerns

- Declining current ratio below 1.0 suggests inability to cover short-term obligations

- Negative working capital indicates potential cash flow problems

- Rapidly growing accounts receivable relative to sales may signal collection issues

- Excessive inventory buildup could indicate obsolescence or demand problems

Leverage Issues

- Debt-to-equity ratios significantly above industry norms increase financial risk

- Growing long-term debt without corresponding asset growth raises sustainability questions

- Declining equity through accumulated losses erodes financial cushion

- High interest coverage requirements strain cash flow

Quality of Assets

- Large goodwill balances from acquisitions risk future impairment charges

- Aging accounts receivable with inadequate allowances may overstate asset values

- Slow inventory turnover suggests potential write-downs

- Unusual related-party transactions may inflate asset values

Equity Structure Concerns

- Negative retained earnings indicate cumulative losses

- Treasury stock purchases during financial difficulty prioritize shareholder returns over stability

- Frequent stock issuance may dilute existing shareholders

- Decreasing book value per share signals deteriorating financial position

Practical Applications and Decision-Making

Balance sheets inform critical business decisions across various stakeholder groups. Understanding how different users analyze balance sheets helps contextualize their importance.

Investors and Shareholders

Investors use balance sheets to evaluate investment opportunities and monitor existing holdings. They focus on equity value, return on equity, book value per share, and asset growth. Balance sheets help assess whether a company is undervalued or overvalued relative to its net worth.

Creditors and Lenders

Banks and bondholders examine balance sheets to evaluate lending risk and determine appropriate interest rates. They prioritize liquidity ratios, debt levels, collateral assets, and working capital. Strong balance sheets typically secure better borrowing terms.

Management

Internal management uses balance sheets for strategic planning, resource allocation, and performance monitoring. They track asset efficiency, optimize capital structure, manage working capital, and identify areas requiring attention or investment.

Suppliers

Vendors review balance sheets before extending trade credit to assess payment risk. They evaluate liquidity ratios, payment history reflected in payables, and overall financial stability to determine credit terms.

Regulatory Agencies

Government bodies and industry regulators monitor balance sheets to ensure compliance with capital requirements, solvency standards, and financial regulations. Banks, insurance companies, and publicly traded firms face particular scrutiny.

Balance Sheet Limitations

Despite their importance, balance sheets have inherent limitations that users must understand for proper interpretation.

Historical Cost Basis

Most assets are recorded at historical cost rather than current market value. This creates a gap between book value and actual worth, particularly for assets held long-term. Real estate purchased decades ago may be worth multiples of its balance sheet value, while rapidly depreciating technology may be overvalued.

Point-in-Time Snapshot

Balance sheets represent a single moment in time. Financial position can change dramatically the day after the balance sheet date. Companies may engage in “window dressing”—timing transactions to present a more favorable position on reporting dates.

Omitted Intangibles

Many valuable intangible assets never appear on balance sheets. Internally developed brand value, customer relationships, employee expertise, and proprietary processes often represent significant value but remain unrecorded unless acquired.

Accounting Policy Variations

Different accounting methods for depreciation, inventory valuation, and revenue recognition create comparability challenges. Two identical companies using different policies will show different balance sheet values.

Off-Balance-Sheet Items

Some obligations and assets don’t appear directly on balance sheets. Operating leases (under old standards), special purpose entities, and certain guarantees may represent real economic obligations while remaining partially or entirely undisclosed.

Balance Sheet Best Practices

Following best practices improves balance sheet quality, usability, and reliability for decision-making.

For Preparers

- Maintain consistent accounting policies across periods for comparability

- Provide detailed notes explaining significant items and changes

- Classify items correctly between current and non-current categories

- Review and update estimates for collectibility, depreciation, and impairments regularly

- Ensure reconciliation between subsidiary ledgers and control accounts

- Document assumptions and judgments affecting balance sheet values

For Analysts

- Compare balance sheets across multiple periods to identify trends

- Benchmark against industry peers for context

- Read footnotes carefully for hidden information and accounting policy details

- Calculate multiple ratios rather than relying on single metrics

- Consider qualitative factors alongside quantitative analysis

- Adjust reported figures for comparability when analyzing different companies

Interactive Balance Sheet Example

Let’s work through an interactive scenario where you can see how transactions affect the balance sheet. Consider a new company, StartupCo, beginning operations with the following initial transactions:

Transaction 1: Initial Investment

Founders invest \$100,000 cash in exchange for common stock.

- Assets increase: Cash +\$100,000

- Equity increases: Common Stock +\$100,000

- Accounting equation: \$100,000 = \$0 + \$100,000 ✓

Transaction 2: Purchase Equipment

Company purchases equipment for \$30,000 cash.

- Assets change: Cash -\$30,000, Equipment +\$30,000

- Total assets remain \$100,000

- Accounting equation: \$100,000 = \$0 + \$100,000 ✓

Transaction 3: Obtain Bank Loan

Company borrows \$50,000 from a bank.

- Assets increase: Cash +\$50,000

- Liabilities increase: Long-term Debt +\$50,000

- Accounting equation: \$150,000 = \$50,000 + \$100,000 ✓

Transaction 4: Purchase Inventory on Credit

Company purchases \$25,000 of inventory from a supplier on 30-day terms.

- Assets increase: Inventory +\$25,000

- Liabilities increase: Accounts Payable +\$25,000

- Accounting equation: \$175,000 = \$75,000 + \$100,000 ✓

StartupCo Balance Sheet After All Transactions

| Assets | Amount ($) |

|---|---|

| Cash | 120,000 |

| Inventory | 25,000 |

| Equipment | 30,000 |

| Total Assets | 175,000 |

| Liabilities & Equity | Amount ($) |

|---|---|

| Accounts Payable | 25,000 |

| Long-term Debt | 50,000 |

| Total Liabilities | 75,000 |

| Common Stock | 100,000 |

| Total Equity | 100,000 |

| Total Liabilities and Equity | 175,000 |

Notice how each transaction maintains the accounting equation’s balance. This double-entry system ensures mathematical accuracy and provides a complete picture of how business activities affect financial position.

Conclusion

Balance sheets serve as foundational financial statements that reveal a company’s financial position at any given moment. By showing what a company owns, owes, and the residual value belonging to shareholders, balance sheets enable informed decision-making across all stakeholder groups.

Understanding balance sheet components—assets, liabilities, and equity—provides the basis for financial analysis. Calculating key ratios like current ratio, debt-to-equity, and working capital offers insights into liquidity, leverage, and operational efficiency. Comparing balance sheets across periods and against industry benchmarks reveals trends and relative performance.

While balance sheets have limitations including historical cost accounting and point-in-time snapshots, they remain indispensable tools when used properly. Combined with income statements and cash flow statements, balance sheets complete the picture of financial health and performance, enabling stakeholders to assess risk, value businesses, and make strategic decisions with confidence.

Whether you’re an investor evaluating opportunities, a manager monitoring operations, or a creditor assessing risk, mastering balance sheet analysis is fundamental to financial literacy and success in business.