Virtual memory is one of the most fundamental concepts in modern operating systems, enabling efficient memory management and providing crucial abstractions that make multitasking possible. This comprehensive guide explores the intricacies of virtual memory, including paging, segmentation, and address translation mechanisms.

What is Virtual Memory?

Virtual memory is a memory management technique that provides an abstraction layer between the physical memory (RAM) and the programs running on a system. It creates an illusion for each process that it has access to a large, contiguous block of memory, even when the physical memory may be fragmented or insufficient.

The primary benefits of virtual memory include:

- Memory Protection: Processes cannot access each other’s memory spaces

- Memory Efficiency: Only actively used portions of programs need to be in physical memory

- Program Isolation: Each program operates in its own virtual address space

- Simplified Programming: Programmers don’t need to worry about physical memory layout

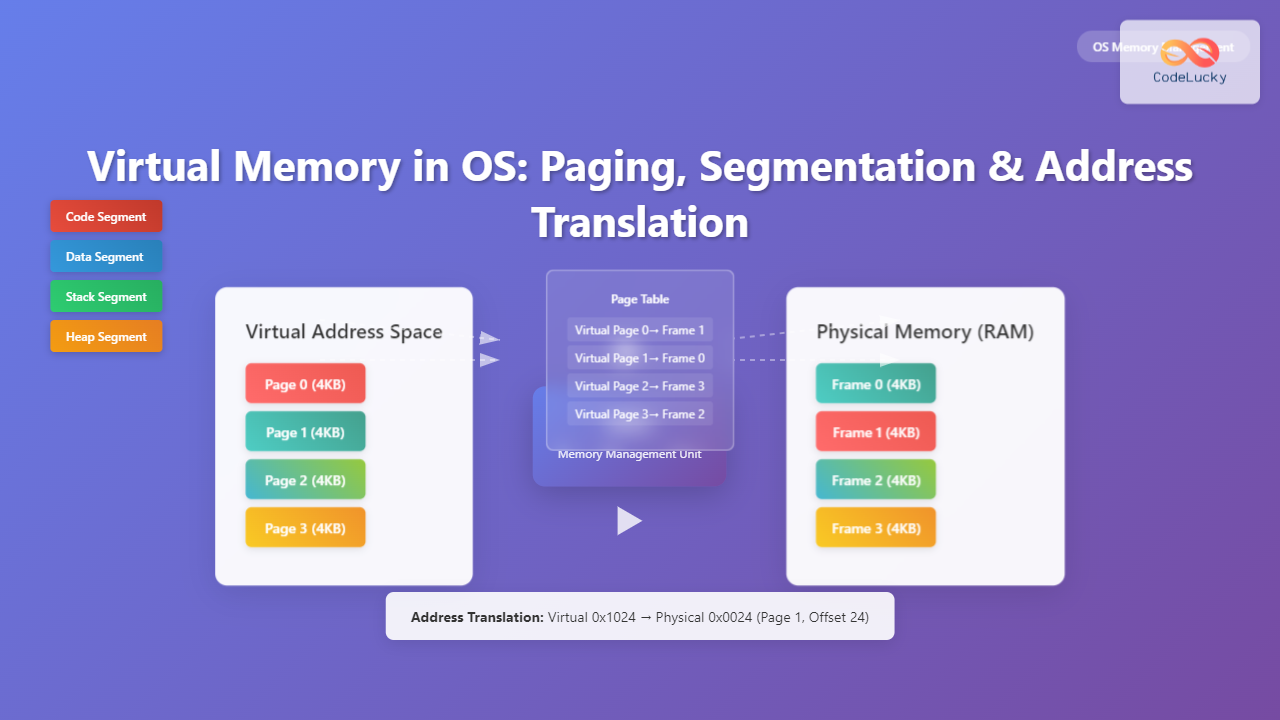

Address Translation Fundamentals

Address translation is the core mechanism that converts virtual addresses used by programs into physical addresses in RAM. This process is handled by the Memory Management Unit (MMU), a specialized hardware component.

Virtual vs Physical Addresses

When a program references memory, it uses virtual addresses. These addresses are translated by the MMU into physical addresses that correspond to actual locations in RAM.

// Example: C program using virtual addresses

int main() {

int variable = 42;

int *ptr = &variable

printf("Virtual address: %p\n", (void*)ptr);

printf("Value: %d\n", *ptr);

return 0;

}

// Output might be:

// Virtual address: 0x7fff5fbff6ac

// Value: 42

The address 0x7fff5fbff6ac is a virtual address. The actual physical location in RAM might be completely different, such as 0x12345678.

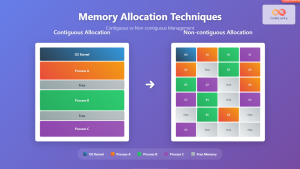

Paging: Page-Based Memory Management

Paging is a memory management scheme that divides both virtual and physical memory into fixed-size blocks called pages and frames, respectively.

Page Structure

In a typical paging system:

- Page: Fixed-size block of virtual memory (usually 4KB)

- Frame: Fixed-size block of physical memory (same size as pages)

- Page Table: Data structure mapping virtual pages to physical frames

Address Translation in Paging

Virtual addresses in paging systems are divided into two parts:

- Page Number: Used as an index into the page table

- Page Offset: Combined with the frame number to form the physical address

Virtual Address Structure (32-bit system with 4KB pages):

┌─────────────────────┬─────────────────────┐

│ Page Number │ Page Offset │

│ (20 bits) │ (12 bits) │

└─────────────────────┴─────────────────────┘

Here’s a practical example of address translation:

def translate_address(virtual_addr, page_table):

"""

Translate virtual address to physical address using paging

Args:

virtual_addr: Virtual address as integer

page_table: Dictionary mapping page numbers to frame numbers

"""

page_size = 4096 # 4KB pages

# Extract page number and offset

page_number = virtual_addr // page_size

page_offset = virtual_addr % page_size

# Look up frame number in page table

if page_number in page_table:

frame_number = page_table[page_number]

physical_addr = frame_number * page_size + page_offset

return physical_addr

else:

raise Exception("Page fault: Page not in memory")

# Example usage

page_table = {

0: 3, # Virtual page 0 maps to physical frame 3

1: 1, # Virtual page 1 maps to physical frame 1

2: 4, # Virtual page 2 maps to physical frame 4

}

virtual_address = 5120 # Address in virtual page 1 (5120 = 1 * 4096 + 1024)

physical_address = translate_address(virtual_address, page_table)

print(f"Virtual: {virtual_address} -> Physical: {physical_address}")

# Output: Virtual: 5120 -> Physical: 5120 (frame 1, offset 1024)

Page Table Entries

Each page table entry contains not just the frame number, but also control bits:

Page Table Entry Structure:

┌─────────┬─────────┬─────────┬─────────┬─────────┬─────────────────┐

│ Present │ Read/W │ User │ Accessed│ Dirty │ Frame Number │

│ Bit │ Bit │ Bit │ Bit │ Bit │ (20 bits) │

└─────────┴─────────┴─────────┴─────────┴─────────┴─────────────────┘

- Present Bit: Indicates if the page is currently in physical memory

- Read/Write Bit: Specifies access permissions

- User Bit: Determines if user-mode processes can access the page

- Accessed Bit: Set when the page is accessed

- Dirty Bit: Set when the page is modified

Segmentation: Logical Division of Memory

Segmentation divides memory into variable-sized logical units called segments, each representing a logical component of a program such as code, data, or stack.

Segment Types

Common segment types include:

- Code Segment: Contains executable instructions

- Data Segment: Contains global and static variables

- Stack Segment: Contains local variables and function call information

- Heap Segment: Contains dynamically allocated memory

Segmentation Address Translation

In segmentation, virtual addresses consist of:

- Segment Number: Identifies which segment

- Offset: Position within the segment

// Example: x86 segmented address

struct segment_descriptor {

uint32_t base_address; // Starting physical address

uint32_t limit; // Segment size

uint8_t access_rights; // Permissions and attributes

};

// Address translation function

uint32_t translate_segmented_address(uint16_t segment, uint32_t offset,

struct segment_descriptor *seg_table) {

struct segment_descriptor seg = seg_table[segment];

// Check bounds

if (offset > seg.limit) {

// Segmentation fault

return 0;

}

// Calculate physical address

return seg.base_address + offset;

}

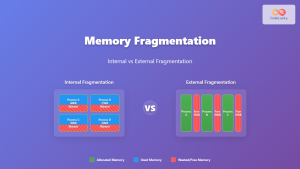

Advantages and Disadvantages of Segmentation

Advantages:

- Logical organization matches program structure

- Easy to implement protection and sharing

- Supports dynamic growth of segments

Disadvantages:

- External fragmentation

- Complex memory allocation

- Variable segment sizes complicate management

Combined Paging and Segmentation

Many modern systems combine both techniques to leverage the benefits of each approach. This hybrid model uses segmentation for logical organization and paging for physical memory management.

Two-Level Address Translation

class HybridMemoryManager:

def __init__(self):

self.segment_table = {}

self.page_tables = {}

self.page_size = 4096

def translate_address(self, segment_num, virtual_page, offset):

"""

Translate address in hybrid paging/segmentation system

"""

# Step 1: Segment translation

if segment_num not in self.segment_table:

raise Exception("Segmentation fault: Invalid segment")

segment_info = self.segment_table[segment_num]

page_table_base = segment_info['page_table_base']

segment_limit = segment_info['limit']

# Check segment bounds

if virtual_page * self.page_size + offset > segment_limit:

raise Exception("Segmentation fault: Address exceeds segment limit")

# Step 2: Page translation

page_table = self.page_tables[page_table_base]

if virtual_page not in page_table:

raise Exception("Page fault: Page not in memory")

physical_frame = page_table[virtual_page]

physical_address = physical_frame * self.page_size + offset

return physical_address

# Example usage

mm = HybridMemoryManager()

# Set up segment table

mm.segment_table[0] = {

'page_table_base': 'code_pt',

'limit': 8192 # 2 pages

}

# Set up page table for code segment

mm.page_tables['code_pt'] = {

0: 5, # Virtual page 0 -> Physical frame 5

1: 8 # Virtual page 1 -> Physical frame 8

}

# Translate address: segment 0, page 1, offset 512

try:

phys_addr = mm.translate_address(0, 1, 512)

print(f"Physical address: {phys_addr}")

# Output: Physical address: 32768 (frame 8 * 4096 + 512)

except Exception as e:

print(f"Translation error: {e}")

Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

The TLB is a high-speed cache that stores recent virtual-to-physical address translations to speed up memory access.

TLB Operation

When a memory access occurs:

- Check TLB for cached translation

- If TLB hit: Use cached physical address

- If TLB miss: Perform full page table lookup and cache result

// Simplified TLB implementation

struct tlb_entry {

uint32_t virtual_page;

uint32_t physical_frame;

uint8_t valid;

uint8_t access_rights;

};

struct tlb_entry tlb[64]; // 64-entry TLB

uint32_t tlb_lookup(uint32_t virtual_page) {

for (int i = 0; i < 64; i++) {

if (tlb[i].valid && tlb[i].virtual_page == virtual_page) {

// TLB hit

return tlb[i].physical_frame;

}

}

// TLB miss - need to check page table

return 0xFFFFFFFF; // Invalid frame number

}

void tlb_update(uint32_t virtual_page, uint32_t physical_frame, int index) {

tlb[index].virtual_page = virtual_page;

tlb[index].physical_frame = physical_frame;

tlb[index].valid = 1;

}

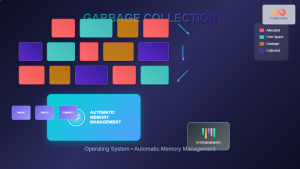

Demand Paging and Page Replacement

Demand paging loads pages into memory only when they are accessed, allowing programs larger than physical memory to run efficiently.

Page Fault Handling

When a program accesses a page not in memory:

- Hardware generates a page fault interrupt

- OS saves the current process state

- OS locates the page on secondary storage

- OS loads the page into an available frame

- OS updates the page table

- OS restarts the interrupted instruction

Page Replacement Algorithms

When physical memory is full, the OS must choose which page to evict:

class PageReplacementSimulator:

def __init__(self, algorithm='lru'):

self.algorithm = algorithm

self.memory = []

self.access_times = {}

self.reference_bits = {}

def lru_replace(self, page_references, memory_size):

"""Least Recently Used replacement"""

memory = []

page_faults = 0

for i, page in enumerate(page_references):

if page not in memory:

page_faults += 1

if len(memory) >= memory_size:

# Find LRU page

lru_page = min(memory,

key=lambda p: self.access_times.get(p, 0))

memory.remove(lru_page)

memory.append(page)

self.access_times[page] = i

return page_faults

def fifo_replace(self, page_references, memory_size):

"""First In, First Out replacement"""

memory = []

page_faults = 0

for page in page_references:

if page not in memory:

page_faults += 1

if len(memory) >= memory_size:

memory.pop(0) # Remove oldest

memory.append(page)

return page_faults

# Example usage

simulator = PageReplacementSimulator()

page_sequence = [1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

lru_faults = simulator.lru_replace(page_sequence, 3)

fifo_faults = simulator.fifo_replace(page_sequence, 3)

print(f"LRU page faults: {lru_faults}")

print(f"FIFO page faults: {fifo_faults}")

Memory Protection and Security

Virtual memory systems provide several security mechanisms:

Access Control Bits

- Read (R): Permission to read from the page

- Write (W): Permission to modify the page

- Execute (X): Permission to execute code from the page

// Example: Setting page permissions

#include

#include

void demonstrate_memory_protection() {

size_t page_size = getpagesize();

// Allocate memory with specific permissions

void *code_page = mmap(NULL, page_size,

PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC, // Read + Execute only

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0);

void *data_page = mmap(NULL, page_size,

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, // Read + Write only

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0);

// Attempting to write to code_page would cause segmentation fault

// Attempting to execute data_page would cause segmentation fault

munmap(code_page, page_size);

munmap(data_page, page_size);

}

Performance Considerations

Virtual memory performance depends on several factors:

Locality of Reference

Programs that exhibit good locality (temporal and spatial) perform better with virtual memory:

- Temporal Locality: Recently accessed pages are likely to be accessed again

- Spatial Locality: Pages near recently accessed pages are likely to be accessed

Working Set

The working set is the collection of pages that a process is actively using. Keeping the working set in physical memory minimizes page faults.

def calculate_working_set(page_references, window_size):

"""

Calculate working set size for different time windows

"""

working_sets = []

for i in range(len(page_references) - window_size + 1):

window = page_references[i:i + window_size]

unique_pages = set(window)

working_sets.append(len(unique_pages))

return working_sets

# Example: Analyze working set behavior

page_refs = [1, 2, 1, 3, 2, 4, 1, 2, 5, 1, 3, 4]

ws_sizes = calculate_working_set(page_refs, 4)

print("Working set sizes:", ws_sizes)

print(f"Average working set size: {sum(ws_sizes) / len(ws_sizes):.2f}")

Modern Virtual Memory Implementations

Contemporary operating systems implement sophisticated virtual memory systems:

Multi-level Page Tables

To handle large address spaces efficiently, modern systems use multi-level page tables:

64-bit x86 Page Table Structure (4-level):

┌─────────┬─────────┬─────────┬─────────┬─────────────┐

│ PML4 │ PDPT │ PD │ PT │ Offset │

│(9 bits) │(9 bits) │(9 bits) │(9 bits) │ (12 bits) │

└─────────┴─────────┴─────────┴─────────┴─────────────┘

Copy-on-Write (COW)

COW optimization shares pages between processes until one attempts to modify them:

// Conceptual COW implementation

struct page {

void *data;

int ref_count;

int is_cow;

};

void handle_cow_fault(struct page *page, void *virtual_addr) {

if (page->ref_count > 1) {

// Make a private copy

struct page *new_page = allocate_page();

memcpy(new_page->data, page->data, PAGE_SIZE);

new_page->ref_count = 1;

new_page->is_cow = 0;

// Update page table to point to new page

update_page_table(virtual_addr, new_page);

// Decrease reference count of original page

page->ref_count--;

} else {

// Just mark as writable

page->is_cow = 0;

set_page_writable(virtual_addr);

}

}

Conclusion

Virtual memory is a cornerstone technology that enables modern computing by providing memory abstraction, protection, and efficient utilization. Understanding the interplay between paging, segmentation, and address translation is crucial for system programmers, kernel developers, and anyone working with low-level system optimization.

The evolution from simple base-and-bound schemes to sophisticated multi-level paging systems with TLBs, demand paging, and advanced replacement algorithms demonstrates the continuous innovation in memory management. As memory hierarchies become more complex with new technologies like persistent memory and disaggregated memory, virtual memory systems continue to adapt and evolve.

Whether you’re debugging performance issues, optimizing memory usage, or designing system software, a solid understanding of virtual memory principles provides the foundation for making informed decisions about memory management strategies.

- What is Virtual Memory?

- Address Translation Fundamentals

- Paging: Page-Based Memory Management

- Segmentation: Logical Division of Memory

- Combined Paging and Segmentation

- Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

- Demand Paging and Page Replacement

- Memory Protection and Security

- Performance Considerations

- Modern Virtual Memory Implementations

- Conclusion