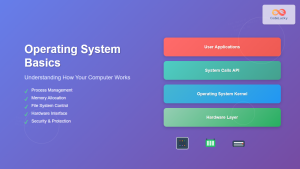

Introduction to Operating System Architecture

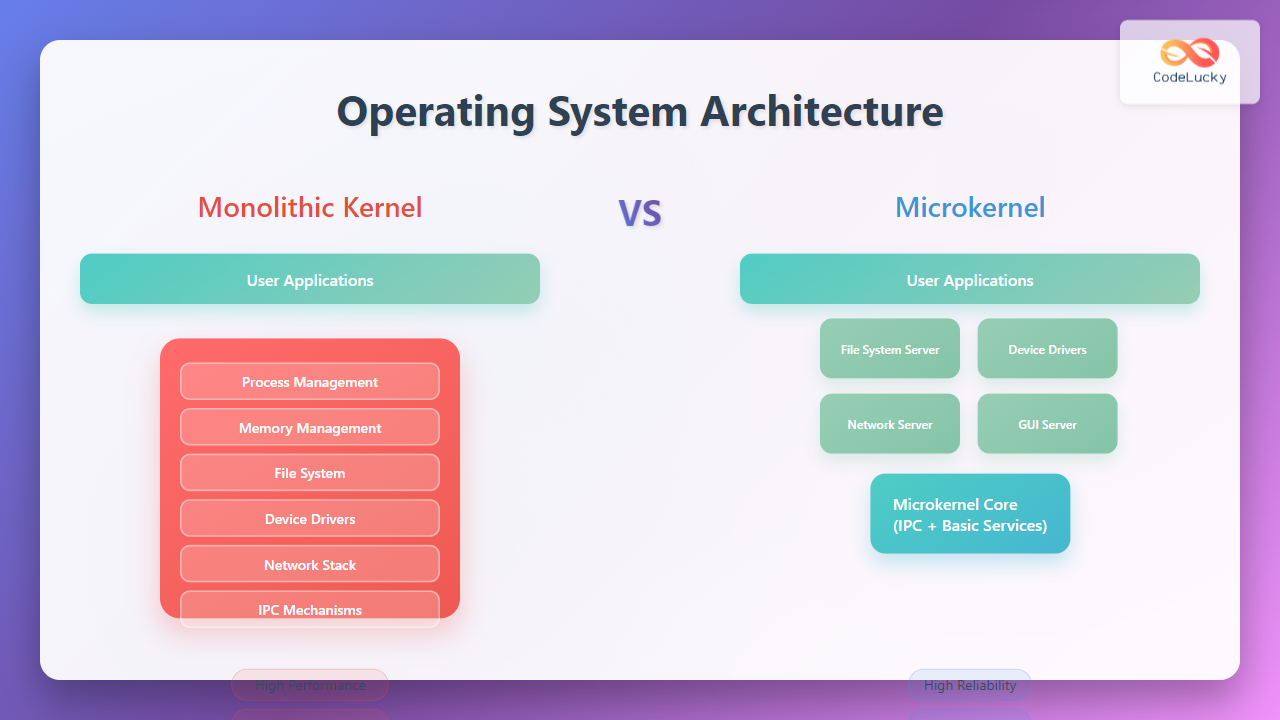

Operating system architecture defines how the core components of an OS are organized and interact with each other. The kernel, being the central component that manages system resources and provides services to applications, can be designed using different architectural approaches. Two fundamental design philosophies dominate modern operating systems: monolithic kernels and microkernels.

Understanding these architectural patterns is crucial for system administrators, developers, and anyone working with operating systems. Each approach offers distinct advantages and trade-offs that influence system performance, reliability, security, and maintainability.

What is a Monolithic Kernel?

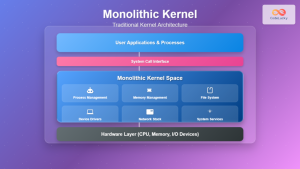

A monolithic kernel is an operating system architecture where the entire kernel runs as a single large process in a single address space. All kernel services, including device drivers, file systems, memory management, and process scheduling, execute in kernel mode with unrestricted access to system resources.

Key Characteristics of Monolithic Kernels

- Single Address Space: All kernel components share the same memory space

- Direct Function Calls: Kernel components communicate through direct function calls

- Privileged Mode Execution: All kernel code runs in supervisor/kernel mode

- Tight Integration: Components are closely coupled and interdependent

- Large Binary Size: The kernel image contains all essential services

Advantages of Monolithic Kernels

Monolithic kernels offer several compelling advantages that make them popular in many production systems:

- High Performance: Direct function calls eliminate overhead of inter-process communication

- Efficient Resource Sharing: Components can directly access shared data structures

- Lower Latency: No context switching between kernel components

- Mature Ecosystem: Extensive driver support and well-tested codebase

- Simplified Development: Easier to implement and debug initially

Disadvantages of Monolithic Kernels

Despite their performance benefits, monolithic kernels have several inherent limitations:

- System Instability: A bug in any kernel component can crash the entire system

- Security Vulnerabilities: Compromise of one component affects the entire kernel

- Maintenance Complexity: Large codebase becomes difficult to maintain and modify

- Limited Modularity: Tight coupling makes it hard to replace or upgrade components

- Memory Usage: All kernel components consume memory even if unused

What is a Microkernel?

A microkernel is a minimalist operating system architecture that implements only the most essential services in kernel space, typically including basic process scheduling, memory management, and inter-process communication. All other services run as user-space servers.

Key Characteristics of Microkernels

- Minimal Kernel: Only essential services run in kernel mode

- User-Space Services: Most OS services run as separate processes

- Message Passing: Components communicate through well-defined IPC mechanisms

- Modular Design: Services can be independently developed and updated

- Principle of Least Privilege: Components run with minimal required privileges

Advantages of Microkernels

Microkernels provide several architectural benefits that enhance system reliability and security:

- System Stability: Failure of one service doesn’t crash the entire system

- Enhanced Security: Isolation between components limits security breaches

- Modularity: Services can be updated or replaced without kernel recompilation

- Fault Tolerance: Failed services can be restarted without system reboot

- Flexibility: Easy to customize and configure for specific use cases

Disadvantages of Microkernels

The microkernel approach also introduces certain performance and complexity challenges:

- Performance Overhead: Message passing is slower than direct function calls

- Context Switching: Frequent mode switches between user and kernel space

- Complex IPC: Sophisticated inter-process communication mechanisms required

- Development Complexity: More complex to design and implement initially

- Resource Usage: Additional overhead for managing separate processes

Detailed Comparison: Monolithic vs Microkernel

Performance Comparison

Performance is often the most critical factor when choosing between architectural approaches:

| Aspect | Monolithic Kernel | Microkernel |

|---|---|---|

| System Call Overhead | Low – Direct function calls | High – Message passing required |

| Memory Performance | Excellent – Shared memory space | Good – Some overhead from isolation |

| I/O Operations | Fast – Direct hardware access | Slower – Through server processes |

| Context Switching | Minimal within kernel | Frequent between services |

Security and Reliability Analysis

| Factor | Monolithic Kernel | Microkernel |

|---|---|---|

| Fault Isolation | Poor – Single point of failure | Excellent – Component isolation |

| Security Boundaries | Weak – All code in kernel space | Strong – Privilege separation |

| System Recovery | Complete reboot required | Service restart possible |

| Attack Surface | Large – Entire kernel exposed | Small – Minimal kernel exposure |

Real-World Examples and Implementations

Popular Monolithic Kernel Operating Systems

Linux is the most prominent example of a successful monolithic kernel design:

- Architecture: Single kernel image with loadable modules

- Performance: Excellent performance for servers and desktops

- Modularity: Kernel modules provide some flexibility

- Use Cases: Web servers, embedded systems, mobile devices

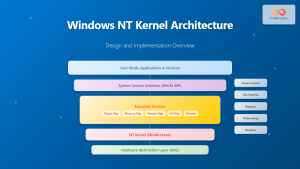

Windows NT Family (Windows 10/11, Server) uses a hybrid approach but is fundamentally monolithic:

- Design: Monolithic kernel with some microkernel concepts

- Components: Executive services run in kernel mode

- Performance: Optimized for desktop and enterprise workloads

Notable Microkernel Operating Systems

QNX represents one of the most successful commercial microkernel implementations:

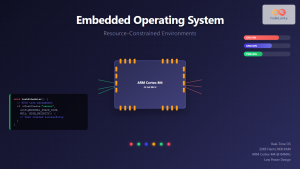

- Real-time Focus: Designed for embedded and real-time systems

- Message Passing: Efficient IPC mechanisms

- Applications: Automotive systems, medical devices, industrial control

- Reliability: Extremely stable and fault-tolerant

MINIX serves as an educational and research microkernel:

- Educational Purpose: Designed to teach OS concepts

- Clean Architecture: Pure microkernel design

- Research Platform: Used for OS research and experimentation

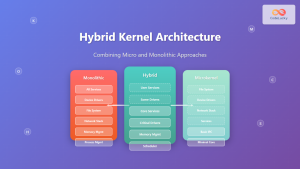

Hybrid Approaches and Modern Trends

Modern operating systems often adopt hybrid approaches that combine elements from both architectural patterns to optimize for specific requirements.

Examples of Hybrid Kernels

macOS (XNU Kernel):

- Combines Mach microkernel with BSD monolithic components

- Message passing for some services, direct calls for performance-critical operations

- Optimized for desktop and mobile computing

Windows NT Architecture:

- Microkernel-inspired design with monolithic implementation

- Executive services run in kernel mode for performance

- User-mode subsystems provide OS personality

Performance Benchmarking and Analysis

System Call Performance Comparison

To illustrate the performance differences, consider a typical file read operation:

Monolithic Kernel (Linux):

1. Application calls read() system call

2. Direct transition to kernel mode

3. VFS layer processes request

4. File system driver handles I/O

5. Device driver executes hardware operation

6. Data returned directly to application

Total: ~2-3 context switchesMicrokernel (QNX):

1. Application calls read() system call

2. Message sent to file system server

3. File system server processes request

4. Message sent to device driver server

5. Device driver executes hardware operation

6. Response messages sent back through chain

7. Data returned to application

Total: ~6-8 context switchesMemory Usage Patterns

| System Component | Monolithic Kernel | Microkernel |

|---|---|---|

| Kernel Code Size | 10-20 MB | 1-2 MB |

| Driver Memory | Kernel space (shared) | User space (isolated) |

| Service Overhead | Minimal | Per-service process overhead |

| Total Memory Usage | Lower overall | Higher due to isolation |

Use Case Scenarios and Recommendations

When to Choose Monolithic Kernels

- High-Performance Computing: Maximum throughput and minimal latency required

- Desktop Systems: Interactive applications benefit from low system call overhead

- Web Servers: High-volume request processing with tight performance requirements

- Gaming Systems: Real-time graphics and audio processing

- Mobile Devices: Battery efficiency and performance optimization

When to Choose Microkernels

- Safety-Critical Systems: Automotive, aerospace, medical devices

- Security-Sensitive Applications: Financial systems, government installations

- Embedded Systems: Custom configurations and reliability requirements

- Research Platforms: Experimental OS development and testing

- Fault-Tolerant Systems: 24/7 operation with minimal downtime

Development and Maintenance Considerations

Development Complexity

Monolithic Kernel Development:

- Simpler initial implementation

- Direct debugging capabilities

- Extensive tooling and documentation available

- Large developer community and resources

- Complex interactions as codebase grows

Microkernel Development:

- Complex initial design and implementation

- Sophisticated IPC mechanisms required

- Distributed debugging challenges

- Smaller but specialized developer community

- Cleaner interfaces and modularity

Long-term Maintenance

| Maintenance Aspect | Monolithic | Microkernel |

|---|---|---|

| Code Updates | Kernel recompilation required | Independent service updates |

| Testing | Full system testing needed | Component-level testing possible |

| Bug Fixing | System-wide impact possible | Isolated to specific services |

| Feature Addition | Kernel modification required | New service development |

Future Trends and Emerging Technologies

Container and Virtualization Impact

Modern containerization technologies are influencing kernel design decisions:

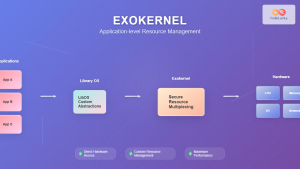

- Unikernels: Application-specific kernel images combining both approaches

- Container-Optimized Kernels: Minimal kernels designed specifically for containerized workloads

- Serverless Computing: Event-driven architectures favoring microkernel-like modularity

Security-First Design

Security considerations are driving architectural evolution:

- Zero-Trust Kernels: Microkernel principles applied to security

- Hardware Security Features: CPU-level isolation supporting microkernel designs

- Formal Verification: Mathematical proof of kernel correctness

Conclusion

The choice between monolithic and microkernel architectures represents a fundamental trade-off between performance and reliability. Monolithic kernels excel in high-performance scenarios where system call overhead must be minimized, making them ideal for desktop systems, servers, and mobile devices. Their mature ecosystem and development tooling provide additional advantages for mainstream operating systems.

Microkernels shine in safety-critical and security-sensitive applications where system stability and fault isolation are paramount. While they incur performance penalties due to message passing overhead, their modular design and enhanced reliability make them suitable for embedded systems, real-time applications, and research platforms.

Modern operating systems increasingly adopt hybrid approaches, incorporating the best aspects of both architectures. As computing requirements continue to evolve, we can expect further innovation in kernel design, potentially leading to new architectural patterns that address emerging challenges in security, performance, and maintainability.

Understanding these architectural principles enables developers and system administrators to make informed decisions when selecting operating systems for specific use cases, ultimately leading to more robust and efficient computing environments.

- Introduction to Operating System Architecture

- What is a Monolithic Kernel?

- What is a Microkernel?

- Detailed Comparison: Monolithic vs Microkernel

- Real-World Examples and Implementations

- Hybrid Approaches and Modern Trends

- Performance Benchmarking and Analysis

- Use Case Scenarios and Recommendations

- Development and Maintenance Considerations

- Future Trends and Emerging Technologies

- Conclusion