The Fractional Knapsack problem is one of the most fundamental optimization problems in computer science. It introduces the idea of maximizing profit while respecting a carrying capacity constraint. Unlike the 0/1 Knapsack problem, fractional knapsack allows us to break items and take fractional parts, making it easier to solve with a greedy approach. In this article, we will explore the Greedy Algorithm and the Dynamic Programming approach to solve the Fractional Knapsack, compare their efficiencies, and walk through illustrative examples.

What is the Fractional Knapsack Problem?

The problem can be described as follows:

- We have n items with specific values and weights.

- We are given a capacity W knapsack (bag).

- We must maximize the total value of items placed inside the knapsack.

- Unlike 0/1 Knapsack, we can take fractions of items instead of being forced to take the whole item or none.

Greedy Choice Property in Fractional Knapsack

The greedy approach works optimally in fractional knapsack because we can always choose the item (or part of it) which provides the highest value per unit weight until we run out of capacity.

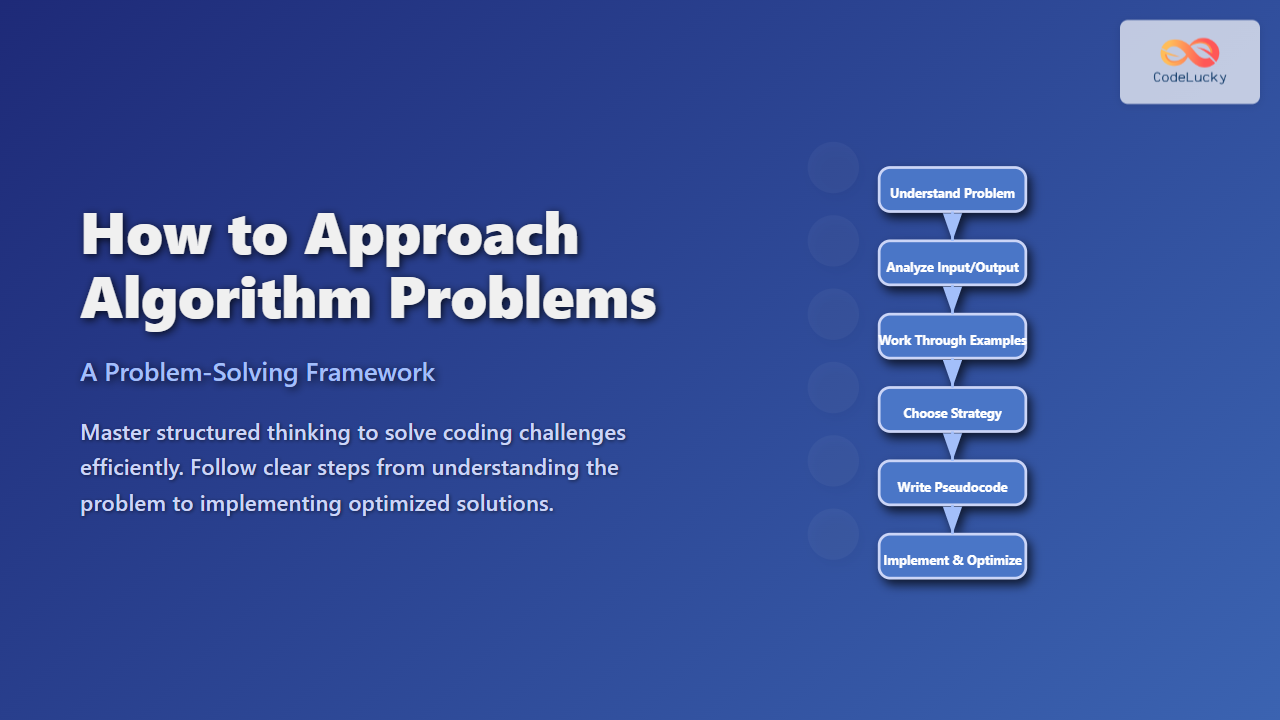

Algorithm Steps

- Compute the value/weight ratio for each item.

- Sort items in descending order of their ratio.

- Start picking items from the top until the knapsack reaches capacity.

- If an item cannot fit completely, take its fractional part.

Example of Fractional Knapsack (Greedy)

Suppose we have the following items and the knapsack capacity W = 50:

| Item | Value | Weight | Value/Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | 10 | 6 |

| 2 | 100 | 20 | 5 |

| 3 | 120 | 30 | 4 |

Process:

- Take Item 1 completely (Weight 10, Value 60).

- Take Item 2 completely (Weight 20, Value 100).

- Remaining capacity = 20, take 20/30 fraction of Item 3.

Total Value = 60 + 100 + (20/30 * 120) = 240.

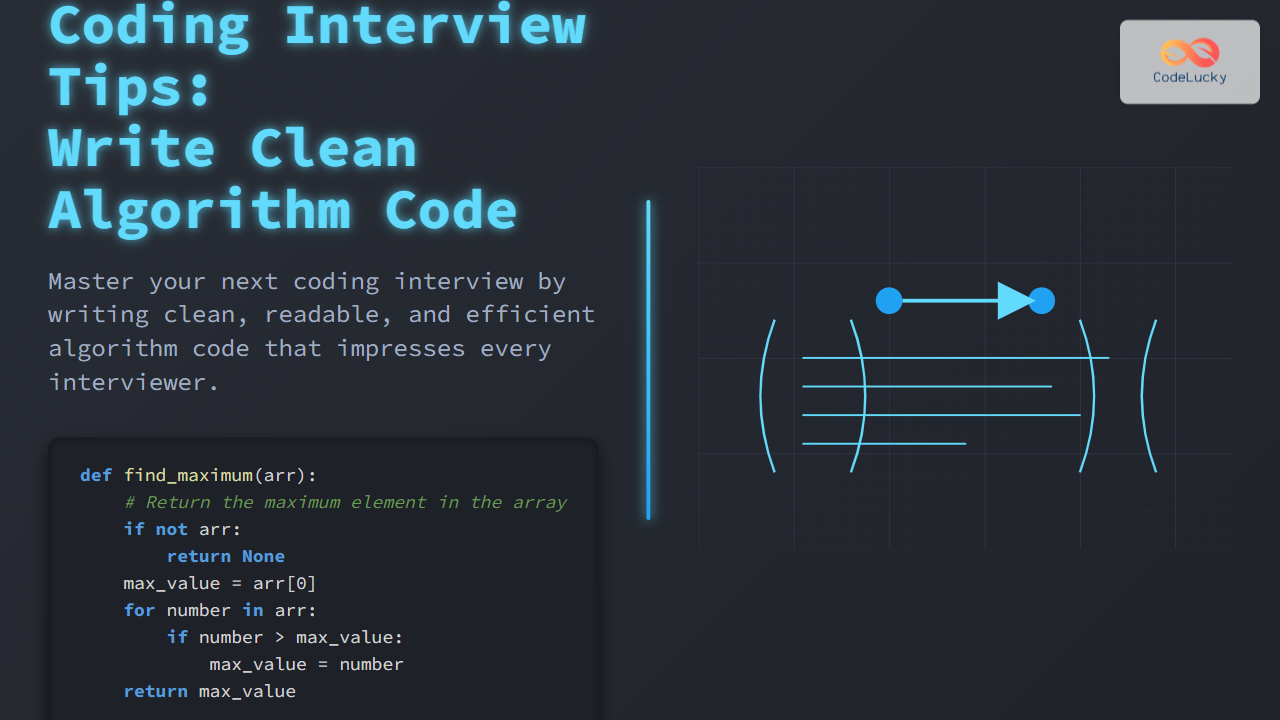

Python Implementation of Greedy Approach

# Fractional Knapsack using Greedy

def fractional_knapsack(values, weights, capacity):

ratio_items = [(v/w, v, w) for v, w in zip(values, weights)]

ratio_items.sort(reverse=True)

total_value = 0

for ratio, v, w in ratio_items:

if capacity >= w:

capacity -= w

total_value += v

else:

total_value += ratio * capacity

break

return total_value

values = [60, 100, 120]

weights = [10, 20, 30]

capacity = 50

print("Maximum value (Greedy):", fractional_knapsack(values, weights, capacity))

Dynamic Programming Approach to Knapsack

For completeness, we can also apply Dynamic Programming (DP) to knapsack problems. However, classical DP is used for 0/1 Knapsack. Since Fractional Knapsack allows fractions, DP is not efficient or necessary. Yet, here is how DP works conceptually:

In the case of 0/1 Knapsack, DP explores all subsets but Fractional Knapsack does not require it.

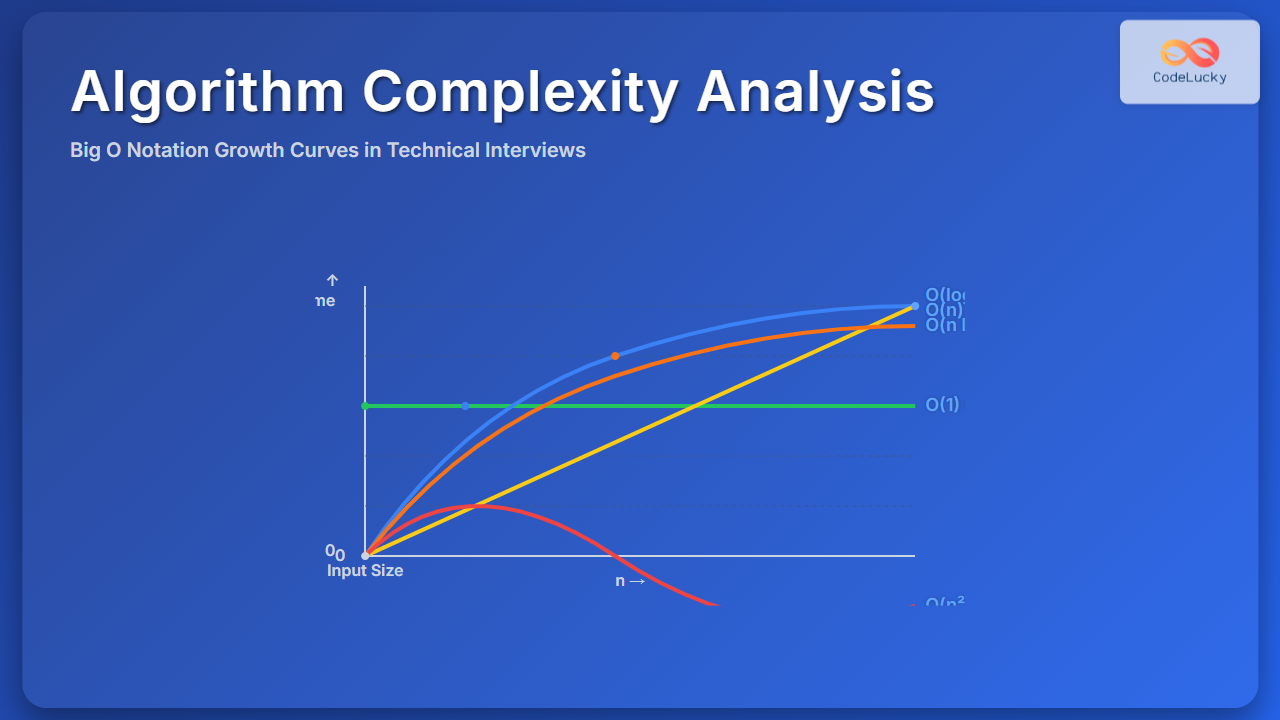

Comparing Greedy vs Dynamic Programming

| Aspect | Greedy (Fractional) | Dynamic Programming (0/1) |

|---|---|---|

| Fractions allowed? | Yes | No |

| Time Complexity | O(n log n) due to sorting | O(nW) where W = capacity |

| Optimal Solution? | Yes | Yes |

| When to Use | If fractions are allowed | If only whole items count |

Visual Understanding

Interactive Thought Experiment

Imagine carrying a treasure bag in a game. Every item has weight and value. Should you take a full golden statue (heavy but less efficient) or multiple small gems (lighter but more efficient)? Greedy tells you to load gems first, then add fraction of the statue if room remains. Dynamic Programming does not allow breaking the statue—it forces a decision between whole items, which can be computationally more complex.

Key Takeaways

- Fractional Knapsack is best solved using a Greedy Algorithm.

- Its time complexity is O(n log n) due to sorting by ratio.

- Dynamic Programming applies only to 0/1 Knapsack.

- Always compute the value/weight ratio when deciding item priority.

By understanding both approaches, programmers can confidently choose between Greedy for fractional knapsack and Dynamic Programming for 0/1 knapsack depending on problem requirements.