Understanding File System Implementation

File system implementation is a critical component of operating systems that manages how data is stored, organized, and retrieved on storage devices. At its core, a file system consists of several key structures: the boot block, super block, and inodes. These components work together to provide a hierarchical organization of files and directories while ensuring efficient storage utilization and data integrity.

Modern file systems like ext4, XFS, and Btrfs all implement these fundamental concepts, though with varying degrees of complexity and optimization. Understanding these structures is essential for system administrators, developers, and anyone working with low-level storage operations.

Boot Block: The Foundation

The boot block is the first block of a file system and contains the bootstrap loader code necessary to boot the operating system. This block is typically 512 bytes or 1024 bytes in size and is located at the very beginning of the partition or storage device.

Boot Block Structure

The boot block contains several critical components:

- Boot signature: A magic number (usually 0xAA55) that identifies the block as bootable

- Partition table: Information about disk partitions (in MBR systems)

- Bootstrap code: Machine code that initializes the boot process

- File system identifier: Indicates the type of file system present

Here’s an example of examining a boot block using hexdump:

# View the boot block of /dev/sda1

sudo hexdump -C /dev/sda1 | head -20

# Output example:

00000000 eb 58 90 4e 54 46 53 20 20 20 20 00 02 08 00 00 |.X.NTFS .....|

00000010 00 00 00 00 00 f8 00 00 3f 00 ff 00 00 08 00 00 |........?.......|

00000020 00 00 00 00 80 00 80 00 7f 33 13 00 00 00 00 00 |.........3......|

Boot Block Functionality

When a computer starts, the BIOS or UEFI firmware reads the boot block to determine how to load the operating system. The boot block may contain:

- Stage 1 bootloader: Basic code that loads the more complex Stage 2 bootloader

- Partition information: Details about how the disk is divided

- File system parameters: Basic metadata about the file system structure

Super Block: File System Metadata Central

The super block is the control block that contains metadata about the entire file system. It’s typically located immediately after the boot block and serves as the central repository for file system configuration and state information.

Super Block Contents

A typical super block contains the following information:

- File system size: Total number of blocks in the file system

- Block size: Size of each data block (commonly 4KB)

- Free space information: Number of free blocks and inodes

- Mount count: Number of times the file system has been mounted

- Magic number: Identifies the file system type

- Creation timestamp: When the file system was created

- Last check time: When the file system was last checked for errors

Here’s how you can examine super block information on a Linux system:

# Display super block information for ext4 file system

sudo dumpe2fs /dev/sda1 | head -20

# Sample output:

Filesystem volume name: /

Last mounted on: /

Filesystem UUID: a1b2c3d4-e5f6-7890-abcd-ef1234567890

Filesystem magic number: 0xEF53

Filesystem revision #: 1 (dynamic)

Filesystem features: has_journal ext_attr resize_inode dir_index filetype needs_recovery extent 64bit flex_bg sparse_super large_file huge_file uninit_bg dir_nlink extra_isize

Filesystem flags: signed_directory_hash

Default mount options: user_xattr acl

Filesystem state: clean

Errors behavior: Continue

Filesystem OS type: Linux

Inode count: 1966080

Block count: 7864064

Reserved block count: 393203

Free blocks: 6234567

Free inodes: 1654321

Super Block Redundancy

Most modern file systems maintain multiple copies of the super block to prevent data loss. For example, ext2/3/4 file systems store backup super blocks at specific intervals:

# List backup super block locations

sudo dumpe2fs /dev/sda1 | grep "Backup superblock"

# Output example:

Backup superblock at 32768, Group descriptors at 32769-32770

Backup superblock at 98304, Group descriptors at 98305-98306

Backup superblock at 163840, Group descriptors at 163841-163842

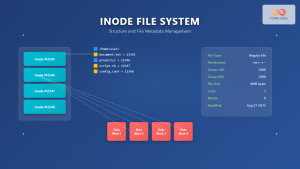

Inodes: The File Metadata Repository

Inodes (index nodes) are data structures that store metadata about files and directories. Each file or directory in a Unix-like file system has an associated inode that contains all the information about the file except its name and actual data.

Inode Structure and Contents

An inode typically contains the following information:

- File type: Regular file, directory, symbolic link, etc.

- Permissions: Read, write, execute permissions for owner, group, and others

- Link count: Number of hard links pointing to this inode

- Owner information: User ID (UID) and Group ID (GID)

- File size: Size of the file in bytes

- Timestamps: Access time, modification time, change time

- Block pointers: Addresses of data blocks containing file content

Examining Inodes

You can examine inode information using various Linux commands:

# Display inode information for a file

ls -li /etc/passwd

# Output example:

1048577 -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 2847 2024-01-15 10:30 /etc/passwd

# Get detailed inode information

stat /etc/passwd

# Output example:

File: /etc/passwd

Size: 2847 Blocks: 8 IO Block: 4096 regular file

Device: 801h/2049d Inode: 1048577 Links: 1

Access: (0644/-rw-r--r--) Uid: ( 0/ root) Gid: ( 0/ root)

Access: 2024-01-15 08:15:30.123456789 +0000

Modify: 2024-01-15 10:30:45.987654321 +0000

Change: 2024-01-15 10:30:45.987654321 +0000

Birth: 2024-01-10 14:22:15.555666777 +0000

Block Addressing in Inodes

Inodes use a sophisticated addressing scheme to handle files of various sizes efficiently:

- Direct blocks: Typically 12 pointers directly to data blocks (for small files)

- Single indirect: Points to a block containing pointers to data blocks

- Double indirect: Points to a block of single indirect blocks

- Triple indirect: Points to a block of double indirect blocks

This addressing scheme allows efficient storage of both small and large files:

# Calculate maximum file size with 4KB blocks and 32-bit block addresses

# Direct blocks: 12 * 4KB = 48KB

# Single indirect: (4KB / 4 bytes) * 4KB = 4MB

# Double indirect: (4KB / 4 bytes)² * 4KB = 4GB

# Triple indirect: (4KB / 4 bytes)³ * 4KB = 4TB

# Total theoretical maximum: ~4TB (in practice, limited by other factors)

File System Layout and Organization

The complete layout of a typical Unix-style file system demonstrates how boot blocks, super blocks, and inodes work together:

Block Groups

Large file systems are divided into block groups to improve performance and reduce fragmentation:

# Display block group information

sudo dumpe2fs /dev/sda1 | grep -A 5 "Group 0"

# Sample output:

Group 0: (Blocks 0-32767)

Primary superblock at 0, Group descriptors at 1-1

Reserved GDT blocks at 2-512

Block bitmap at 513 (+513), Inode bitmap at 529 (+529)

Inode table at 545-672 (+545)

24815 free blocks, 8048 free inodes, 2 directories

Practical Implementation Examples

Creating a Custom File System

Here’s a simplified example of how these components might be implemented:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <time.h>

// Super block structure

struct superblock {

uint32_t magic_number; // 0x12345678 for our custom FS

uint32_t block_size; // Size of each block

uint32_t total_blocks; // Total number of blocks

uint32_t free_blocks; // Number of free blocks

uint32_t total_inodes; // Total number of inodes

uint32_t free_inodes; // Number of free inodes

uint32_t first_data_block; // First block containing data

time_t creation_time; // File system creation time

time_t last_mount_time; // Last mount time

uint16_t mount_count; // Number of mounts since last check

};

// Inode structure

struct inode {

uint16_t mode; // File type and permissions

uint16_t uid; // Owner user ID

uint32_t size; // File size in bytes

time_t atime; // Last access time

time_t mtime; // Last modification time

time_t ctime; // Last change time

uint16_t gid; // Owner group ID

uint16_t links_count; // Number of hard links

uint32_t blocks; // Number of 512-byte blocks allocated

uint32_t direct_blocks[12]; // Direct block pointers

uint32_t indirect_block; // Single indirect block pointer

uint32_t double_indirect; // Double indirect block pointer

uint32_t triple_indirect; // Triple indirect block pointer

};

// Example function to read super block

int read_superblock(int fd, struct superblock *sb) {

// Seek to super block location (typically block 1)

lseek(fd, 1024, SEEK_SET);

// Read super block

if (read(fd, sb, sizeof(struct superblock)) != sizeof(struct superblock)) {

return -1;

}

// Verify magic number

if (sb->magic_number != 0x12345678) {

return -1;

}

return 0;

}

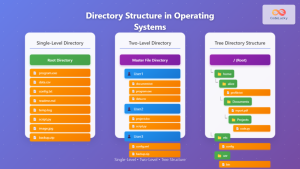

Directory Implementation

Directories are special files that contain mappings from filenames to inode numbers:

// Directory entry structure

struct dir_entry {

uint32_t inode_number; // Inode number of the file

uint16_t record_length; // Length of this directory entry

uint8_t name_length; // Length of the filename

uint8_t file_type; // File type indicator

char name[]; // Variable-length filename

};

// Example of reading directory entries

void read_directory(int fd, uint32_t inode_num) {

struct inode dir_inode;

struct dir_entry entry;

// Read directory inode

read_inode(fd, inode_num, &dir_inode);

// Read directory data blocks

for (int i = 0; i < 12 && dir_inode.direct_blocks[i]; i++) {

lseek(fd, dir_inode.direct_blocks[i] * block_size, SEEK_SET);

// Read directory entries from this block

int offset = 0;

while (offset < block_size) {

read(fd, &entry, sizeof(struct dir_entry));

printf("Inode: %u, Name: %.*s\n",

entry.inode_number, entry.name_length, entry.name);

offset += entry.record_length;

}

}

}

File System Operations

Understanding how common file system operations interact with these structures is crucial:

File Creation Process

When creating a new file, the file system must:

- Allocate an inode: Find a free inode from the inode bitmap

- Initialize inode: Set metadata like permissions, timestamps, and owner

- Update directory: Add directory entry mapping filename to inode number

- Update super block: Decrement free inode count

- Allocate data blocks: If data is written immediately

# Monitor file creation with strace

strace -e trace=file touch newfile.txt

# Output shows system calls:

openat(AT_FDCWD, "newfile.txt", O_WRONLY|O_CREAT|O_NOCTTY|O_NONBLOCK, 0666) = 3

fstat(3, {st_mode=S_IFREG|0664, st_size=0, ...}) = 0

close(3) = 0

Performance Considerations

The design of boot blocks, super blocks, and inodes significantly impacts file system performance:

Caching Strategies

- Super block caching: Keep super block in memory to avoid repeated disk reads

- Inode caching: Cache frequently accessed inodes

- Directory caching: Cache directory entries for faster path resolution

Optimization Techniques

# View file system cache statistics

cat /proc/meminfo | grep -E "(Buffers|Cached)"

# Output example:

Buffers: 245760 kB

Cached: 1847296 kB

# Monitor inode cache usage

cat /proc/sys/fs/inode-nr

# Output: current_inodes unused_inodes max_inodes

# Example: 85234 12456 0

Error Handling and Recovery

File system integrity depends on proper handling of these critical structures:

Consistency Checking

File system checkers (fsck) verify the consistency of boot blocks, super blocks, and inodes:

# Check file system consistency

sudo fsck.ext4 -n /dev/sda1

# Sample output showing checks:

e2fsck 1.45.5 (07-Jan-2020)

/dev/sda1: clean, 284537/1966080 files, 1629497/7864064 blocks

# Force check with detailed output

sudo fsck.ext4 -f -v /dev/sda1

# Output includes:

Pass 1: Checking inodes, blocks, and sizes

Pass 2: Checking directory structure

Pass 3: Checking directory connectivity

Pass 4: Checking reference counts

Pass 5: Checking group summary information

Backup and Recovery

Critical file system structures should be backed up:

# Backup super block

sudo dd if=/dev/sda1 of=superblock_backup bs=1024 count=1 skip=1

# List all super block locations for recovery

sudo dumpe2fs /dev/sda1 | grep "Backup superblock" | head -3

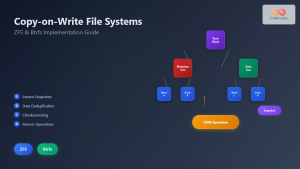

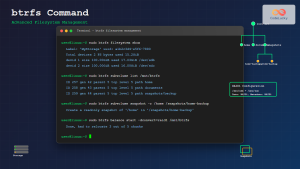

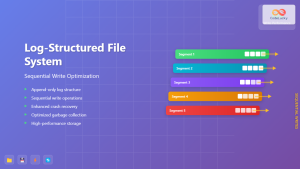

Modern File System Enhancements

Contemporary file systems have evolved these basic concepts:

Journal Integration

Journaling file systems maintain transaction logs to ensure consistency:

- Metadata journaling: Log changes to inodes and directory structures

- Full data journaling: Log both metadata and data changes

- Ordered mode: Write data before committing metadata changes

Extended Attributes

Modern inodes support extended attributes for additional metadata:

# Set extended attribute

setfattr -n user.author -v "John Doe" myfile.txt

# List extended attributes

getfattr -d myfile.txt

# Output:

# file: myfile.txt

# user.author="John Doe"

Conclusion

The boot block, super block, and inode structures form the foundation of file system implementation in modern operating systems. The boot block provides the essential bootstrap code for system initialization, the super block maintains critical file system metadata and configuration, while inodes store comprehensive file metadata and enable efficient data organization.

Understanding these structures is fundamental for system administrators managing storage systems, developers working with file I/O operations, and anyone involved in operating system development. The sophisticated addressing schemes, caching strategies, and error recovery mechanisms built around these core concepts enable modern file systems to deliver the reliability and performance required by today’s computing environments.

As storage technology continues to evolve with NVMe SSDs, persistent memory, and distributed file systems, these foundational concepts remain relevant while being enhanced with new features like copy-on-write, snapshots, and advanced compression techniques.

- Understanding File System Implementation

- Boot Block: The Foundation

- Super Block: File System Metadata Central

- Inodes: The File Metadata Repository

- File System Layout and Organization

- Practical Implementation Examples

- File System Operations

- Performance Considerations

- Error Handling and Recovery

- Modern File System Enhancements

- Conclusion