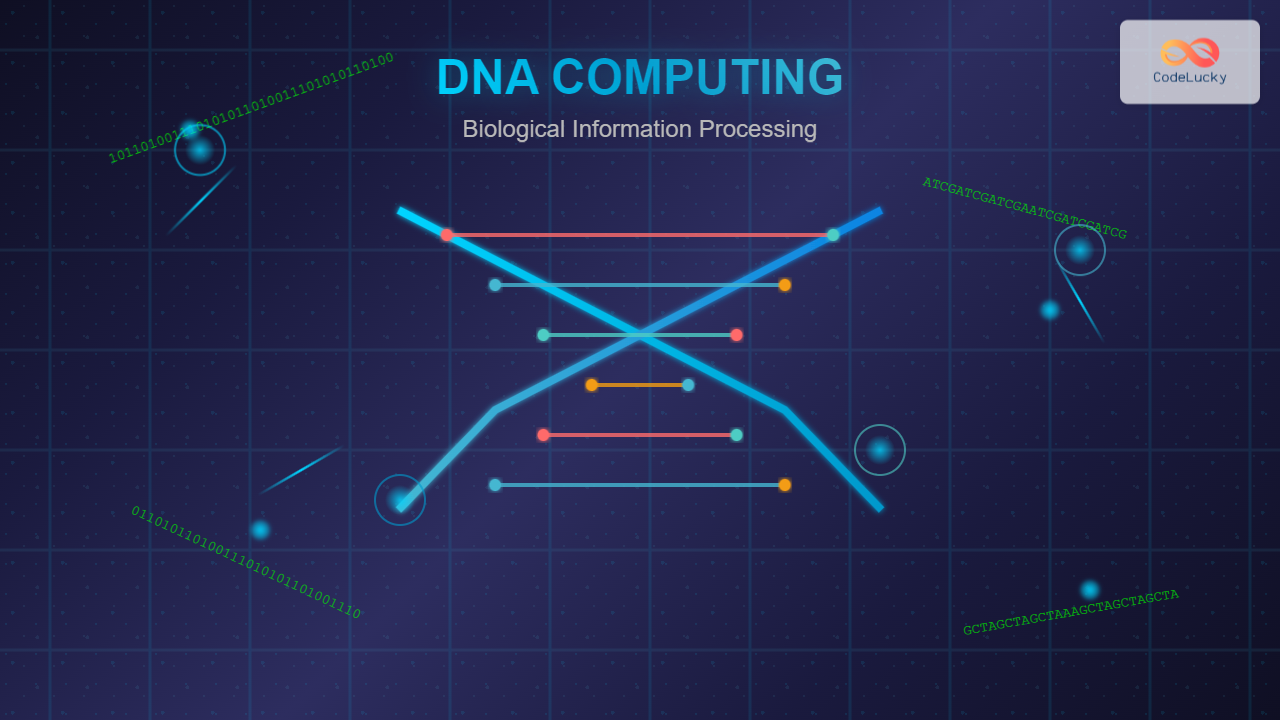

Introduction to DNA Computing

DNA computing represents a revolutionary paradigm in computational science, utilizing the inherent information storage and processing capabilities of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) molecules. This biological approach to computation leverages the same molecular mechanisms that store genetic information in living organisms to perform complex mathematical and logical operations.

Unlike traditional silicon-based computing systems that process information through electronic circuits, DNA computing harnesses the natural properties of DNA molecules to encode, store, and manipulate data at the molecular level. This biomolecular computing approach offers unprecedented parallelism, massive storage density, and energy efficiency that far exceeds conventional computing architectures.

Fundamental Principles of DNA Computing

DNA Structure and Information Encoding

DNA molecules consist of four nucleotide bases: adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C). These bases form complementary pairs (A-T and G-C) through hydrogen bonds, creating the characteristic double helix structure. In DNA computing, these four bases serve as the fundamental alphabet for encoding binary and higher-order information.

The complementary base pairing rules enable error detection and correction mechanisms inherent in DNA structure. When DNA strands hybridize (bind together), mismatched bases create structural distortions that can be detected and corrected, providing natural error-checking capabilities for computational processes.

Molecular Operations and Computational Primitives

DNA computing utilizes various molecular biological operations to perform computational tasks. These operations manipulate DNA strands to execute algorithms and solve complex problems:

- Hybridization: Complementary DNA strands bind together, enabling pattern matching and template-based operations

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): Amplifies specific DNA sequences, serving as a molecular copy operation

- Restriction Enzyme Cutting: Cleaves DNA at specific recognition sequences, performing conditional branching operations

- Ligation: Joins DNA fragments together, concatenating information sequences

- Gel Electrophoresis: Separates DNA by size, enabling sorting and selection operations

DNA Computing Algorithms and Implementation

Adleman’s Hamiltonian Path Problem

The foundational work in DNA computing was Leonard Adleman’s 1994 solution to the Hamiltonian Path Problem using DNA molecules. This groundbreaking experiment demonstrated that biological molecules could solve NP-complete computational problems through massive parallelism.

In this approach, each city is represented by a unique DNA sequence, and flight connections between cities are encoded as complementary DNA strands. A valid Hamiltonian path corresponds to a complete DNA strand that hybridizes with all city sequences exactly once.

Boolean Logic Operations

DNA computing can implement fundamental Boolean logic gates through molecular interactions. These biological logic gates form the foundation for more complex computational operations:

AND Gate Implementation:

Input A: 5'-ATCG-3'

Input B: 5'-CGTA-3'

Template: 3'-TAGC-GCAT-5'

Result: Complete hybridization occurs only when both inputs are present

Output: 5'-ATCGCGTA-3' (logical AND result)

OR Gate Implementation:

Uses multiple templates with partial complementarity

Any input binding produces output signal

Implements logical OR through parallel pathwaysArithmetic Operations in DNA

DNA computing systems can perform arithmetic operations through molecular manipulations. Addition, for example, can be implemented using DNA strand displacement reactions:

DNA Addition Example (2 + 3 = 5):

Operand 1: AA (represents 2)

Operand 2: AAA (represents 3)

Catalyst strand initiates concatenation

Result: AAAAA (represents 5)

Multiplication through repeated addition:

3 × 4 implemented as 3 + 3 + 3 + 3

Uses cyclical DNA reactions

Amplification controls repetition countAdvanced DNA Computing Architectures

DNA Finite Automata

DNA molecules can implement finite state machines, enabling complex pattern recognition and string processing operations. These biological automata process input sequences and transition between states based on molecular recognition events.

Parallel Processing Capabilities

One of DNA computing’s greatest advantages is its inherent massive parallelism. A single test tube containing DNA solutions can perform billions of computational operations simultaneously, with each molecule representing an independent processing unit.

Parallel Algorithm Execution

Parallel Search Example:

Problem: Find needle in haystack (10^12 elements)

Traditional: Sequential search O(n) time

DNA Computing: Generate all possible solutions simultaneously

1. Create 10^12 different DNA strands (one per element)

2. Add target sequence as probe

3. Hybridization occurs only with matching strand

4. Detect hybridized products

5. Result obtained in parallel O(1) molecular timePractical Applications and Use Cases

Cryptography and Security

DNA computing offers unique advantages for cryptographic applications due to its molecular-level security and inherent randomness. DNA-based encryption systems can provide unbreakable security through molecular key distribution:

- Quantum-resistant encryption: DNA’s molecular nature provides protection against quantum computing attacks

- One-time pads: Random DNA sequences generate truly random encryption keys

- Steganography: Information hidden within apparently normal DNA sequences

- Molecular authentication: Unique DNA signatures for identity verification

Optimization Problems

DNA computing excels at solving complex optimization problems that require exploring vast solution spaces:

Database Operations and Data Mining

DNA’s information density enables unprecedented database storage and retrieval capabilities. A single gram of DNA can theoretically store 455 exabytes of data, making it ideal for long-term archival storage and massive dataset operations.

DNA Database Query Example:

Query: SELECT * FROM users WHERE age > 25 AND city = 'NewYork'

DNA Implementation:

1. Each record encoded as unique DNA strand

2. Age condition: restriction enzyme cuts strands where age ≤ 25

3. City condition: probe hybridizes only with 'NewYork' sequences

4. Surviving strands represent query results

5. PCR amplification retrieves matching recordsTechnical Challenges and Limitations

Error Rates and Reliability

DNA computing faces several technical challenges that limit its practical implementation:

- Thermal noise: Random molecular motion can cause unwanted reactions

- Cross-hybridization: Non-specific binding between DNA strands

- Enzyme efficiency: Incomplete reactions leave partially processed results

- DNA degradation: Molecular breakdown over time affects computation reliability

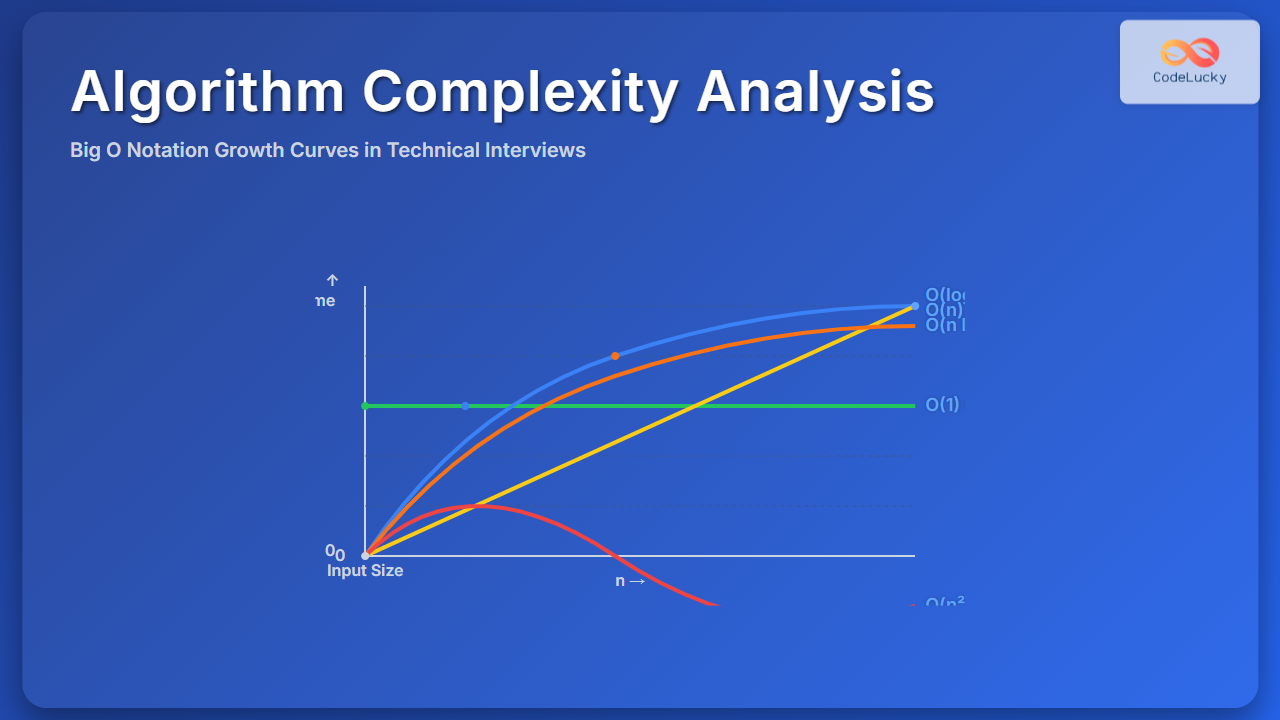

Scalability and Speed Considerations

While DNA computing offers massive parallelism, it faces scalability challenges in terms of reaction time and result extraction:

Performance Comparison:

Operation Type | Silicon Computer | DNA Computer

Simple Addition | Nanoseconds | Minutes to Hours

Complex Search | Hours to Days | Minutes (parallel)

Storage Density | GB per device | Exabytes per gram

Energy Efficiency | Watts | Near-zero energy

Error Rate | 10^-17 | 10^-4 to 10^-6Current Research and Future Directions

Hybrid DNA-Silicon Systems

Researchers are developing hybrid systems that combine DNA computing’s parallel processing capabilities with traditional silicon computers’ speed and precision. These systems leverage the strengths of both paradigms:

- DNA preprocessing: Massive parallel search and filtering

- Silicon postprocessing: Fast sequential operations and result analysis

- Interface protocols: Converting between molecular and electronic signals

- Error correction: Silicon systems verify and correct DNA computation results

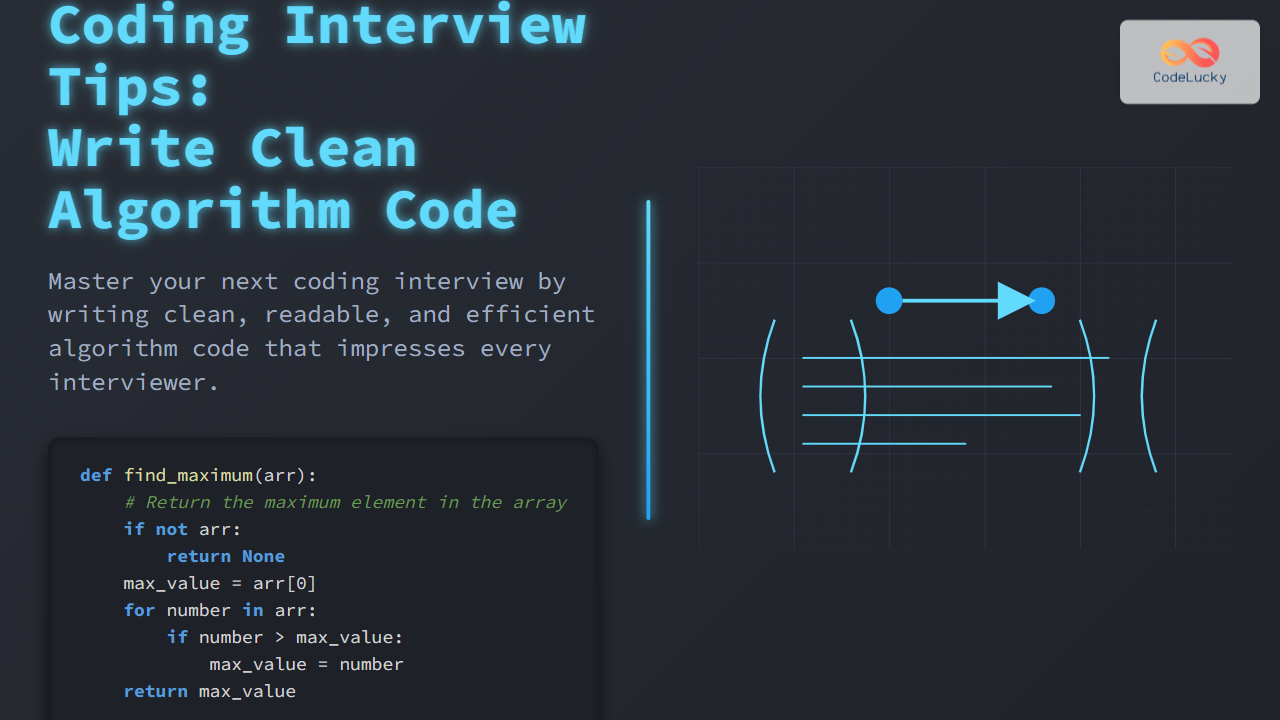

Programmable DNA Computers

Advanced DNA computing systems are becoming increasingly programmable, allowing researchers to design custom molecular algorithms for specific applications:

Implementation Example: DNA-Based Pattern Matching

Here’s a practical example of implementing pattern matching using DNA computing principles:

Problem: Find pattern "ATCG" in sequence "GGATCGTTA"

DNA Implementation:

1. Target sequence: 5'-GGATCGTTA-3'

2. Probe pattern: 3'-TAGC-5' (complement of ATCG)

3. Hybridization conditions: 37°C, salt buffer

4. Detection: Fluorescent labeling of probe

5. Result: Fluorescence indicates pattern match at position 2

Molecular Steps:

Step 1: Denature target DNA (95°C)

Step 2: Add complementary probe (cooling to 37°C)

Step 3: Allow hybridization (30 minutes incubation)

Step 4: Wash unbound probes

Step 5: Detect fluorescent signal

Step 6: Quantify match strengthComparison with Traditional Computing Paradigms

DNA computing represents a fundamentally different approach to information processing compared to conventional computing systems:

| Aspect | Traditional Computing | DNA Computing |

|---|---|---|

| Processing Model | Sequential/Limited Parallel | Massive Parallel |

| Storage Medium | Silicon/Magnetic | Molecular/Biological |

| Energy Consumption | High (Watts to Kilowatts) | Extremely Low (Near Zero) |

| Storage Density | Terabytes per Device | Exabytes per Gram |

| Processing Speed | Gigahertz | Minutes to Hours |

| Error Correction | Engineered Systems | Natural Mechanisms |

Conclusion and Future Prospects

DNA computing represents a paradigm shift in computational thinking, offering unique solutions to problems that challenge traditional computing architectures. While current limitations in speed and reliability prevent widespread practical deployment, ongoing research continues to address these challenges.

The future of DNA computing lies in specialized applications where its unique advantages—massive parallelism, incredible storage density, and energy efficiency—outweigh its limitations. As biotechnology advances and our understanding of molecular information processing deepens, DNA computing may become an essential complement to traditional computing systems.

The convergence of biology and computer science through DNA computing opens new frontiers in computation, promising revolutionary advances in data storage, parallel processing, and bio-compatible computing systems. This biological approach to information processing demonstrates that nature’s four-billion-year optimization of molecular information systems holds the key to solving some of our most challenging computational problems.