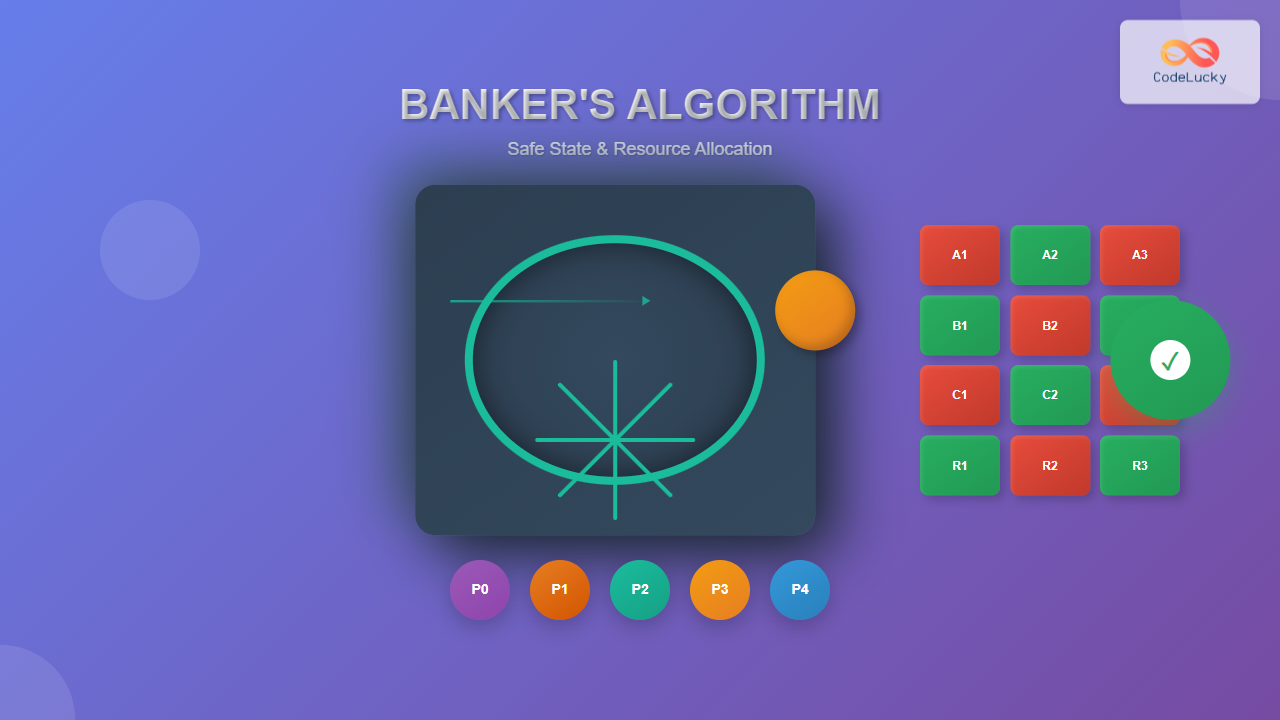

The Banker’s Algorithm is a fundamental deadlock avoidance algorithm in operating systems, designed to ensure that resource allocation maintains the system in a safe state. Named after the banking principle of maintaining sufficient reserves, this algorithm prevents deadlocks by carefully analyzing resource requests before granting them.

Understanding the Banker’s Algorithm

Developed by Edsger Dijkstra, the Banker’s Algorithm simulates the allocation of predetermined maximum resources to processes and determines whether the system can remain in a safe state after each allocation. The algorithm maintains several data structures to track current allocations, maximum needs, and available resources.

Key Data Structures

The Banker’s Algorithm relies on three primary matrices and one vector:

Available Vector (Available[m])

Represents the number of available instances of each resource type. If Available[j] = k, then k instances of resource type Rj are available.

Max Matrix (Max[n][m])

Defines the maximum demand of each process for each resource type. If Max[i][j] = k, then process Pi may request at most k instances of resource type Rj.

Allocation Matrix (Allocation[n][m])

Shows the number of resources of each type currently allocated to each process. If Allocation[i][j] = k, then process Pi is currently allocated k instances of resource type Rj.

Need Matrix (Need[n][m])

Represents the remaining resource need of each process. Calculated as: Need[i][j] = Max[i][j] - Allocation[i][j]

Safe State Concept

A system state is considered safe if there exists a sequence of processes (called a safe sequence) such that:

- For each process Pi in the sequence, the resources that Pi can still request can be satisfied by currently available resources plus resources held by all processes Pj where j < i

- If Pi‘s resource needs cannot be immediately satisfied, it can wait until all processes Pj (where j < i) have completed and released their resources

Algorithm Implementation

Safety Algorithm

The safety algorithm determines if the current system state is safe:

1. Initialize Work = Available and Finish[i] = false for all i

2. Find an index i such that:

- Finish[i] == false

- Need[i] <= Work

3. If no such i exists, go to step 5

4. Set Work = Work + Allocation[i] and Finish[i] = true

5. If Finish[i] == true for all i, the system is in a safe stateResource-Request Algorithm

When process Pi requests resources represented by Requesti:

1. If Request[i] <= Need[i], go to step 2; otherwise, raise error

2. If Request[i] <= Available, go to step 3; otherwise, P[i] must wait

3. Pretend to allocate requested resources:

Available = Available - Request[i]

Allocation[i] = Allocation[i] + Request[i]

Need[i] = Need[i] - Request[i]

4. If the resulting state is safe, complete the allocation

5. If unsafe, restore the original state and make P[i] waitDetailed Example

Consider a system with 5 processes (P0-P4) and 3 resource types (A, B, C):

Initial System State

| Process | Allocation (A,B,C) | Max (A,B,C) | Need (A,B,C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P0 | (0,1,0) | (7,5,3) | (7,4,3) |

| P1 | (2,0,0) | (3,2,2) | (1,2,2) |

| P2 | (3,0,2) | (9,0,2) | (6,0,0) |

| P3 | (2,1,1) | (2,2,2) | (0,1,1) |

| P4 | (0,0,2) | (4,3,3) | (4,3,1) |

Available Resources: (3,3,2)

Safety Check Process

Step-by-Step Safety Verification

Step 1: Work = (3,3,2), all Finish[i] = false

Step 2: Find process where Need ≤ Work

- P1: Need(1,2,2) ≤ Work(3,3,2) ✓

- Work = (3,3,2) + (2,0,0) = (5,3,2), Finish[1] = true

Step 3: Continue with updated Work

- P3: Need(0,1,1) ≤ Work(5,3,2) ✓

- Work = (5,3,2) + (2,1,1) = (7,4,3), Finish[3] = true

Step 4: Continue the process

- P4: Need(4,3,1) ≤ Work(7,4,3) ✓

- Work = (7,4,3) + (0,0,2) = (7,4,5), Finish[4] = true

Step 5: Continue

- P2: Need(6,0,0) ≤ Work(7,4,5) ✓

- Work = (7,4,5) + (3,0,2) = (10,4,7), Finish[2] = true

Step 6: Final check

- P0: Need(7,4,3) ≤ Work(10,4,7) ✓

- Work = (10,4,7) + (0,1,0) = (10,5,7), Finish[0] = true

Safe Sequence: <P1, P3, P4, P2, P0>

Resource Request Example

Suppose process P1 requests (1,0,2). Let’s check if this request can be granted:

Request Validation

Request[1] = (1,0,2)

Need[1] = (1,2,2)

Check: Request[1] <= Need[1]

(1,0,2) <= (1,2,2) ✓

Check: Request[1] <= Available

(1,0,2) <= (3,3,2) ✓Temporary Allocation

| Matrix | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| Available | (3,3,2) | (2,3,0) |

| Allocation[1] | (2,0,0) | (3,0,2) |

| Need[1] | (1,2,2) | (0,2,0) |

Safety Check After Request

With the new state, we verify safety:

- Available: (2,3,0)

- Find P3: Need(0,1,1) > Available(2,3,0) at resource C ✗

- Find P1: Need(0,2,0) ≤ Available(2,3,0) ✓

After P1 completes: Available = (2,3,0) + (3,0,2) = (5,3,2)

Continue with P3, P4, P2, P0… The system remains safe, so the request is granted.

Implementation in Pseudocode

function isSafe(available, max, allocation, processes, resources):

need = calculateNeed(max, allocation)

work = available.copy()

finish = [false] * processes

safeSequence = []

count = 0

while count < processes:

found = false

for i in range(processes):

if not finish[i] and need[i] <= work:

work += allocation[i]

finish[i] = true

safeSequence.append(i)

found = true

count += 1

break

if not found:

return false, []

return true, safeSequence

function requestResources(processId, request, available, max, allocation):

need = calculateNeed(max, allocation)

if request > need[processId]:

return "Error: Request exceeds maximum claim"

if request > available:

return "Process must wait: Insufficient resources"

# Simulate allocation

available -= request

allocation[processId] += request

need[processId] -= request

safe, sequence = isSafe(available, max, allocation, processes, resources)

if safe:

return "Request granted", sequence

else:

# Restore original state

available += request

allocation[processId] -= request

need[processId] += request

return "Request denied: Unsafe state"Advantages and Limitations

Advantages

- Deadlock Prevention: Guarantees deadlock-free execution

- Predictable: Deterministic resource allocation decisions

- Fair: All processes eventually get required resources

- Efficient: Optimal resource utilization when properly tuned

Limitations

- Prior Knowledge: Requires advance declaration of maximum resource needs

- Static Resources: Number of resources must remain constant

- Fixed Process Count: Number of processes should be known beforehand

- Conservative: May deny safe requests to maintain safety

Real-World Applications

The Banker’s Algorithm finds applications in various scenarios:

- Operating Systems: Memory and CPU allocation in multitasking environments

- Database Systems: Lock management and transaction scheduling

- Distributed Systems: Resource allocation across network nodes

- Cloud Computing: Virtual machine resource provisioning

- Banking Systems: Credit allocation and risk management

Best Practices

- Accurate Estimation: Ensure maximum resource declarations are realistic but not overly conservative

- Regular Monitoring: Track resource utilization patterns to optimize allocation

- Timeout Mechanisms: Implement timeouts for waiting processes to prevent indefinite blocking

- Priority Systems: Consider process priorities when multiple safe allocations are possible

- Dynamic Adjustment: Allow controlled updates to maximum claims when necessary

Conclusion

The Banker’s Algorithm remains a cornerstone of deadlock avoidance in operating systems and resource management. While it requires prior knowledge of resource requirements and maintains conservative allocation policies, its guarantee of deadlock-free execution makes it invaluable for critical systems. Understanding its mechanics, implementation, and limitations is essential for system programmers and computer science students working with concurrent systems and resource allocation problems.

By maintaining safe states through careful analysis of resource requests, the algorithm ensures system stability and prevents the costly overhead of deadlock detection and recovery mechanisms. Modern implementations often combine the Banker’s Algorithm with other techniques to create robust, efficient resource management systems.